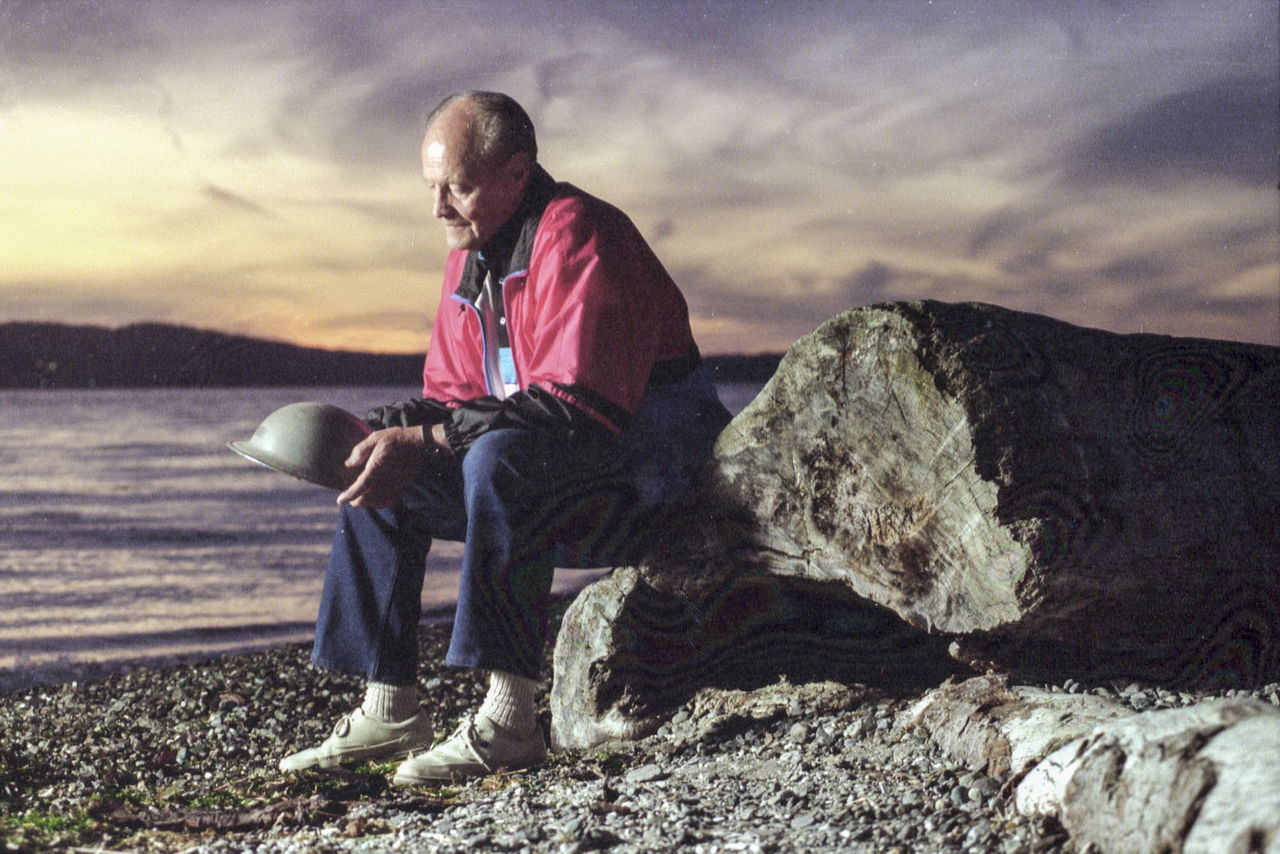

EVERETT — Jack Elkins was the most determined man I ever knew. Even as I write those words I’m still surprised he’s gone. If anyone was going to out-will, out-tough, out-duel death it was Jack Elkins.

Jack died peacefully in Everett on Feb. 17 and even though I’d guessed the end was near, when his grandson called with the news I was knocked off my feet. I always figured Jack Elkins would survive us all.

Let me back up and start at the beginning. I first met Jack on a cloudy summer morning in 1995 when I was a reporter at The Daily Herald working a story about V-J Day, the end of World War II.

We sat at his kitchen table that morning drinking coffee and talking. He was wary at first, unsure if he could trust me and so we skirted carefully around the edges of his life. But what a life it was. He was Jack Elkins — husband, father, grandfather, small business owner and onetime prisoner of the Japanese. Later, as my visits became more frequent, I learned much more about POW 997 and the steel he had inside.

That steel was forged during his capture on Corregidor in 1942 and the hellish ride on a prisoner ship bound for Japan. It was forged in a freezing flea-infested warehouse in Yokohama where his dysentery-wracked body shrank to 100 pounds and he stared at the growing stack of pine boxes that held the ashes of those who died. It was forged when he sliced off half a finger in a POW sawmill and directed another prisoner to sew up what was left with no more than an aspirin to cut the pain. Finally, there was liberation and the uncertain home life where old friends couldn’t possibly understand why he’d changed.

In some ways that Yokohama prison camp never left him. How could it?

Marine veterans who were prisoners of the Japanese have a saying: “Never buy green bananas.” What was understood among that exclusive fraternity is that you might not live to see them ripen. And yet he never blamed the Japanese people afterwards, saw it as war and soldiers and the consequences of a political system.

Jack lived to be 93 years old, ancient for a POW survivor. He had arthritis, emphysema, the ravages of beriberi and malaria, and legs that no longer worked. But his mind never gave an inch. Calling Jack a survivor was like calling an Olympic marathoner a jogger.

He had an indestructible independence and even at the very end was determined, to the frustration of caregivers, to call his own shots. He once told me he could never work for someone else, couldn’t have someone tell him what to do, when to be at work and what to wear. The surest way to get something done was to tell Jack Elkins he couldn’t do it.

He always kept the door open to his room in the assisted living home in Lake Stevens where he lived the last years of his life. Why was the door open? Maybe he had to have a way out.

He kept his room in a precise order, lip balm on the night stand in the exact place every time so he could reach over and know it was there. Black cane at the proper angle on the chair nearby so he could grasp it after he’d pulled himself out of bed and stood there several seconds to steady himself before easing into the wheelchair that waited in its place by the bed. In the final year, moving from bed to wheelchair took a sustained effort that would have broken an ordinary man. That, I thought, was the determination that came from surviving Yokohama.

Over the years, after the newspaper stories were over and a book was published, we didn’t talk much about Corregidor or prison camps. Now we talked about our families and the turns our lives had taken. We had some things in common: Both of us attended Gonzaga University in Spokane and we followed the basketball team each year and talked about the prospects for the upcoming season. We both liked the flat, dry country of Eastern Washington.

He’d ask about my daughter and I’d asked about his grandchildren. Over the years his grandsons grew from grade-schoolers to young men who still visited their grandpa every day. After Jack’s wife, Gladys, died, I would often bring my wife along on my visits and they developed a bond of their own. When I’d show up without her, he’d quickly look around to see if she was there and he couldn’t hide the disappointment when she wasn’t.

“Don’t worry Jack,” I’d say. “I’ll bring Bridget next time.”

About a dozen years ago, Jack was guest of honor at the annual Marine Corps Ball at Naval Air Station Whidbey. Even in his 80s, he filled out his Marine uniform and stood at attention ramrod straight. The youngest Marines were barely 20 years old that night, but they were genuine in their respect for the old warrior. I was proud of Jack and proud of the Marines and honored to be there.

At the end, Jack’s life was reduced to four walls and a bed. One of the last times I saw him he told me that he’d calculated in his head how many days he’d been alive. Over 33,000, he said as if he couldn’t believe it either. I laughed and then remembered that was what he’d done in that Yokohama prison camp, ticking off the days like a calendar in his head. The last I saw him was a few weeks ago in an Everett transitional care facility. He’d fallen and broken a hip but he was talking about getting back on his feet. Jack Elkins was not giving up.

For me, he had long since moved past being the indestructible man, the former POW who had cheated death many times along the way. Now he was just Jack, my friend.

‘Captured Honor’

Bob Wodnik of Everett is a former reporter for The Daily Herald. He met Jack Elkins in 1995 for a story on VJ-Day. Later, he wrote about Elkins in the book “Captured Honor,” published in 2003 by Washington State University Press. In 2004, the book was named one of the “Best of the Best of the University Presses: Books You Should Know About.”

Read Wodnik’s 1995 story about Elkins on HeraldNet: http://bit.ly/1p9TqYy

More about the book “Captured Honor”: http://amzn.to/1QhTpsd

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.