By Matt O’Brien / Associated Press

We may remember 2018 as the year when technology’s dystopian potential became clear, from Facebook’s role enabling the harvesting of our personal data for election interference to a seemingly unending series of revelations about the dark side of Silicon Valley’s connect-everything ethos.

The list is long: High-tech tools for immigration crackdowns. Fears of smartphone addiction. YouTube algorithms that steer youths into extremism. An experiment in gene-edited babies .

Doorbells and concert venues that can pinpoint individual faces and alert police. Repurposing genealogy websites to hunt for crime suspects based on a relative’s DNA. Automated systems that keep tabs of workers’ movements and habits. Electric cars in Shanghai transmitting their every movement to the government.

It’s been enough to exhaust even the most imaginative sci-fi visionaries.

“It doesn’t so much feel like we’re living in the future now, as that we’re living in a retro-future,” novelist William Gibson wrote this month on Twitter. “A dark, goofy ’90s retro-future.”

More awaits us in 2019, as surveillance and data-collection efforts ramp up and artificial intelligence systems start sounding more human , reading facial expressions and generating fake video images so realistic that it will be harder to detect malicious distortions of the truth.

But there are also countermeasures afoot in Congress and state government — and even among tech-firm employees who are more active about ensuring their work is put to positive ends.

“Something that was heartening this year was that accompanying this parade of scandals was a growing public awareness that there’s an accountability crisis in tech,” said Meredith Whittaker, a co-founder of New York University’s AI Now Institute for studying the social implications of artificial intelligence.

The group has compiled a long list of what made 2018 so ominous, though many are examples of the public simply becoming newly aware of problems that have built up for years. Among the most troubling cases was the revelation in March that political data-mining firm Cambridge Analytica swept up personal information of millions of Facebook users for the purpose of manipulating national elections.

“It really helped wake up people to the fact that these systems are actually touching the core of our lives and shaping our social institutions,” Whittaker said.

That was on top of other Facebook disasters, including its role in fomenting violence in Myanmar , major data breaches and ongoing concerns about its hosting of fake accounts for Russian propaganda .

It wasn’t just Facebook. Google attracted concern about its continuous surveillance of users after The Associated Press reported that it was tracking people’s movements whether they like it or not.

It also faced internal dissent over its collaboration with the U.S. military to create drones with “computer vision” to help find battlefield targets and a secret proposal to launch a censored search engine in China. And it unveiled a remarkably human-like voice assistant that sounds so real that people on the other end of the phone didn’t know they were talking to a computer.

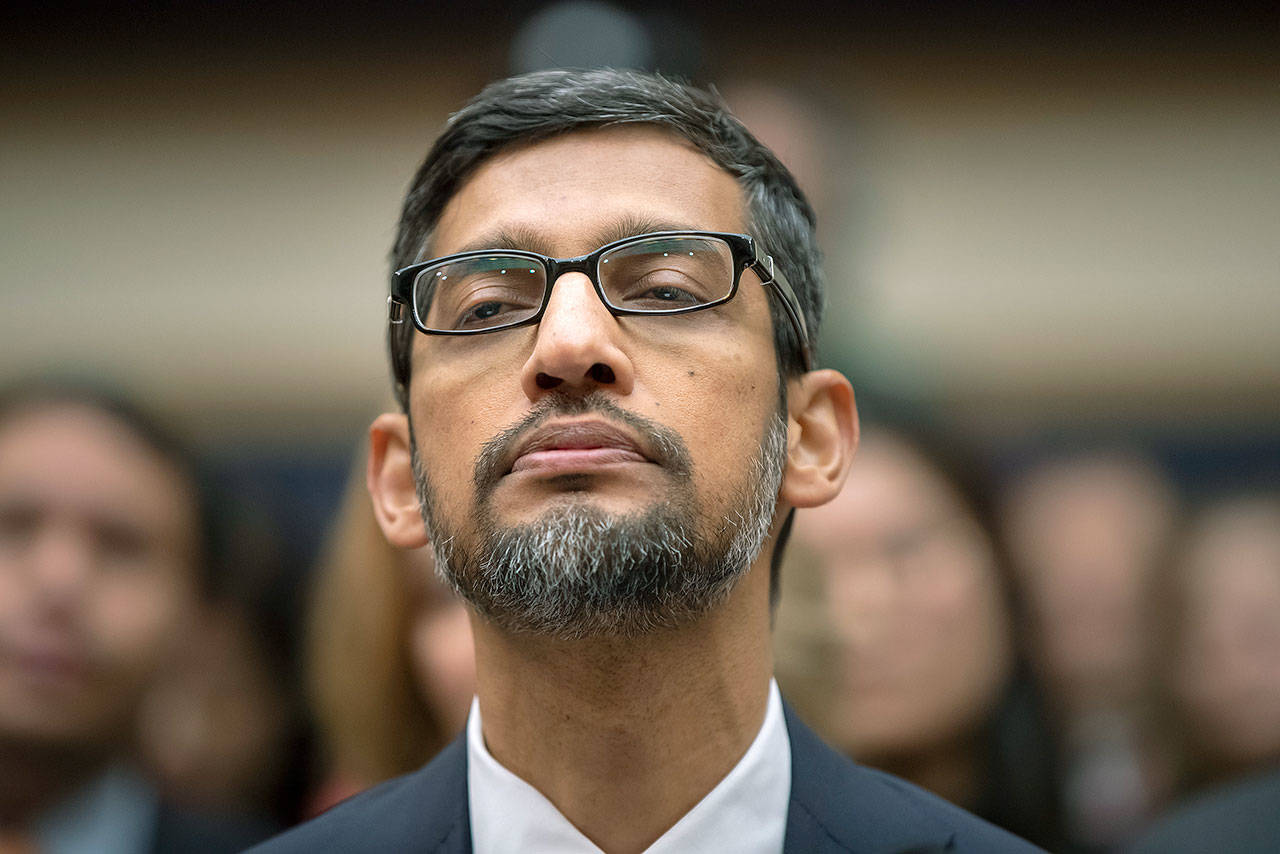

Those and other concerns bubbled up in December as lawmakers grilled Google CEO Sundar Pichai at a congressional hearing — a sequel to similar public reckonings this year with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and other tech executives.

“It was necessary to convene this hearing because of the widening gap of distrust between technology companies and the American people,” Republican House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy said.

Internet pioneer Vint Cerf said he and other engineers never imagined their vision of a worldwide network of connected computers would morph 45 years later into a surveillance system that collects personal information or a propaganda machine that could sway elections.

“We were just trying to get it to work,” recalled Cerf, who is now Google’s chief internet evangelist. “But now that it’s in the hands of the general public, there are people who … want it to work in a way that obviously does harm, or benefits themselves, or disrupts the political system. So we are going to have to deal with that.”

Contrary to futuristic fears of “super-intelligent” robots taking control, the real dangers of our tech era have crept in more prosaically — often in the form of tech innovations we welcomed for making life more convenient .

Part of experts’ concern about the leap into connecting every home device to the internet and letting computers do our work is that the technology is still buggy and influenced by human errors and prejudices. Uber and Tesla were investigated for fatal self-driving car crashes in March, IBM came under scrutiny for working with New York City police to build a facial recognition system that can detect ethnicity, and Amazon took heat for supplying its own flawed facial recognition service to law enforcement agencies.

In some cases, opposition to the tech industry’s rush to apply its newest innovations to questionable commercial uses has come from its own employees. Google workers helped scuttle the company’s Pentagon drone contract, and workers at Amazon, Microsoft and Salesforce sought to cancel their companies’ contracts to supply tech services to immigration authorities.

“It became obvious to a lot of people that the rhetoric of doing good and benefiting society and ‘Don’t be evil’ was not what these companies were actually living up to,” said Whittaker, who is also a research scientist at Google who founded its Open Research group.

At the same time, even some titans of technology have been sounding alarms. Prominent engineers and designers have increasingly spoken out about shielding children from the habit-forming tech products they helped create.

And then there’s Microsoft President Brad Smith, who in December called for regulating facial recognition technology so that the “year 2024 doesn’t look like a page” from George Orwell’s “1984.”

In a blog post and a Washington speech, Smith painted a bleak vision of all-seeing government surveillance systems forcing dissidents to hide in darkened rooms “to tap in code with hand signals on each other’s arms.”

To avoid such an Orwellian scenario, Smith advocates regulating technology so that anyone about to subject themselves to surveillance is properly notified. But privacy advocates argue that’s not enough.

Such debates are already happening in states like Illinois, where a strict facial recognition law has faced tech industry challenges, and California, which in 2018 passed the nation’s most far-reaching law to give consumers more control over their personal data. It takes effect in 2020.

The issue could find new attention in Congress next year as more Republicans warm up to the idea of basic online privacy regulations and the incoming Democratic House majority takes a more skeptical approach to tech firms that many liberal politicians once viewed as allies — and prolific campaign donors.

The “leave them alone” approach of the early internet era won’t work anymore, said Rep. David Cicilline, a Rhode Island Democrat poised to take the helm of the House’s antitrust subcommittee.

“We’re seeing now some of the consequences of the abuses that can occur in these platforms if they remain unregulated without meaningful oversight or enforcement,” Cicilline said.

Too much regulation may bring its own undesirable side effects, Cerf warned.

“It’s funny in a way because this online environment was supposed to remove friction from our ability to transact,” he said. “If in our desire, if not zeal, to protect people’s privacy we throw sand in the gears of everything, we may end up with a very secure system that doesn’t work very well.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.