Marian Harrison and Marilyn Quincy may not think of themselves as historians, but that’s exactly what they are.

They have turned to century-old newspapers, business directories, census reports, tax records, graveyards and their own memories to recover the stories of some of Snohomish County’s earliest African-American residents. Their work started as a way to pass on forgotten family history but soon expanded to include all of the county’s black pioneers — lives that have largely been overlooked by earlier historians.

“I knew my family had been there when Washington became a state,” Quincy said. “I looked up the 1889 census and found that there were three black families in Snohomish County: The Stewarts in Snohomish, the Richardsons in Monroe and the Udells in the Edmonds area.”

Though the information is limited, local historians have found a common narrative for black migration to Snohomish County: Early African-Americans looking to start anew after the demise of slavery settled here to find freedom, gain employment and own land.

The local searches have turned up small yet important facts that reveal the lives of these early residents. For example:

Louisa “Nellie” Donaldson (1849-?) owned the Everett Avenue grocery store and helped found the Second Baptist Church in Everett. George W. Norwood Jr. (1890-1957) served as a soldier in World War I before settling near Arlington. William P. Shafroth (1861-1922) was a Snohomish postman, vegetable farmer and justice of the peace. Jennie Samuels (1868-1948) was a women’s club organizer and tourist home operator for black travelers in Everett.

In their research, Harrison, 85, of Marysville, and Quincy, 72, of Everett, found out that they are distant relatives. They are both related to William P. Stewart, a Civil War veteran. Harrison had an ancestor who married into Stewart’s family; Quincy is his great-granddaughter.

Stewart served in the Civil War with the 29th U.S. Colored Volunteer Infantry. He moved to Snohomish County about 1889 and is buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Snohomish.

“I need to get back into it,” Quincy said of her local black history research, which she shares with the Everett Public Library. “It’s a shame we only think about it one month a year.” (February is Black History Month.)

Here are the recovered stories of five of Snohomish County’s most notable black pioneers:

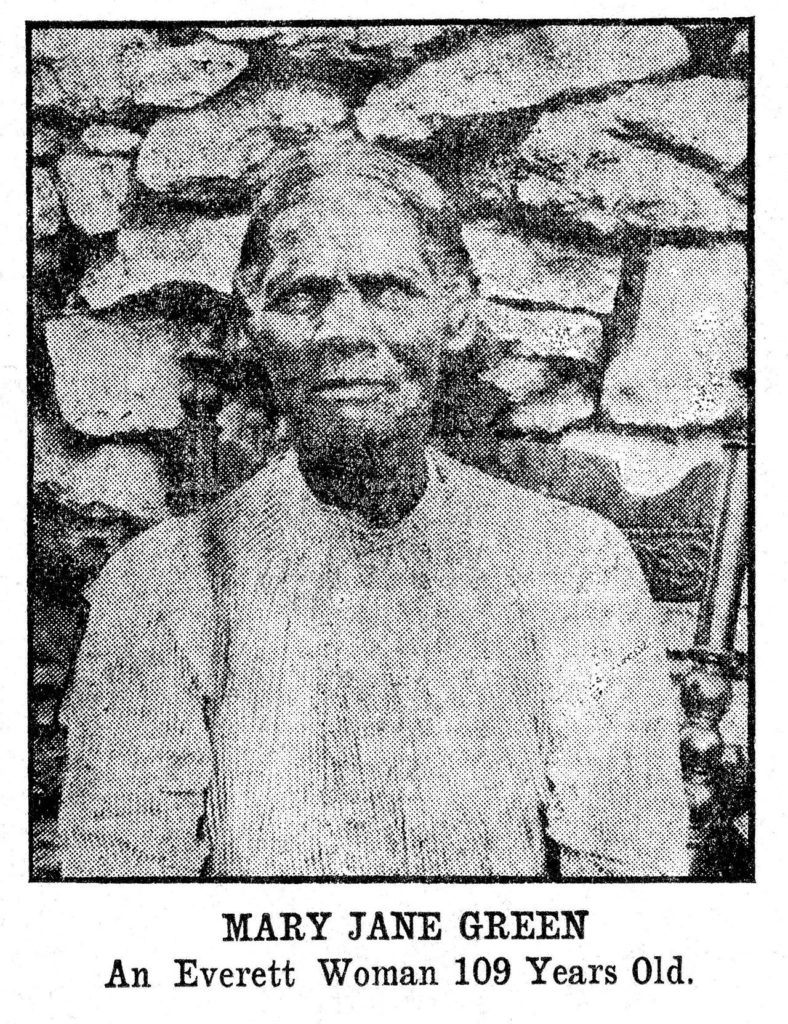

Mary Jane Green (1802-1912) was a former slave and lived to be the oldest resident of Everett on record. She died at 110.

Green is the second-oldest resident to live in Washington, though she held the state record for nearly a century. The oldest on record is Emma Otis (1901-2015) who was 114 years old and living in Poulsbo when she died.

Even at 109, Green remembered “those dark days of slavery” as if they were yesterday, according to a story that ran in the Everett Daily Herald on May 5, 1911.

She was sold as a slave three times. Her family was divided on an auction block in Tennessee. Her first owner bought her and her mother. She never saw her father again.

“One master I had was very bad,” Green told a reporter. “He was born for hell and he is there now.”

She became a mother herself while field laboring in old Virginia. All of her children were born during James Buchanan’s presidency. (Buchanan was the 15th president of the United States, from 1857-1861.)

She moved from Kansas City, Missouri, to Everett to live with her granddaughter, who was the widow of Lewis George Walker, one of nearly 100 victims killed in the Wellington avalanche of 1910. Walker was assistant to the superintendent to the Great Northern Railroad.

A devout Christian, for four years Green walked unassisted the seven blocks from her home on Everett Avenue to Second Baptist Church, then on Rainier Avenue, every Sunday.

She was buried in an unmarked grave in Evergreen Cemetery next to her grandson-in-law. Walker’s gravestone has an inscription noting that he was a Wellington victim. His wife may also be buried nearby in an unmarked grave.

“There isn’t much about Mary Jane Green beyond the article where she’s talking about her slavery years,” Everett historian David Dilgard said. “More than the interview, the photograph of her is pretty powerful. It shows an elderly woman who has seen a whole lot of history.”

Luella Boyer (1869-1912) was perhaps the first African-American businesswoman in Everett. She was a hairdresser and dermatologist who owned a beauty shop in Everett’s theater district. She also worked at the Everett Theatre as a backstage maid.

The Everett Theater Co. paid “Mrs. Boyer” a $1 nightly fee for cleaning the theater (now the Historic Everett Theatre), which still stands on Colby Avenue. She may have also done hairdressing backstage.

She likely met show business legends George Walker and Bert Williams at the Everett Theatre on Jan. 16, 1905 while they were on tour. The song-and-dance comedians, who had recently entertained the king of England, starred in the first all-African-American musical comedy “In Dahomey.”

Born in Idaho, Luella Ruth Brown married John Boyer, a black barber from Pennsylvania, around 1869. They adopted a daughter, Esther, not long after moving to Everett in 1902.

While John sold hair products as a traveling salesman, Luella established and expanded her business. She was known as “Madame Boyer” at the beauty shop. The prefix “Madame” was popularly adopted by black female hairstylists at that time.

Though the couple separated around 1905, the 1910 census maintained the polite lie that she was a widow. (John showed up in the 1920 census for Seattle. He was listed as a wig maker.)

“When he left her, she had to support herself and their little girl, so she used his business connections to start her own line of hair products, do hairdressing for the wealthiest Everett residents, and eventually she expanded her beauty salon,” Snohomish County historian Margaret Summitt said.

She also gave talks at a Sunday forum sponsored by The Seattle Republican, a newspaper with a former slave as its publisher, on social issues of the time, including racial discrimination and prostitution of black women.

In 1910, Luella remarried to Bertrand Brent, a white man from Missouri who worked as a waiter in a restaurant in 1910 and a janitor for the Everett Public Library in 1911.

She and her new husband purchased property in Snohomish and King counties. They owned six lots in all.

A year after she remarried, Luella died at 43 from diabetes. Her grave in the Evergreen Cemetery is marked “Luella R. Brent.”

Manima Wilson (1886-1949) is believed to be the first black woman to graduate from the University of Washington.

Wilson was also the first African-American to graduate from Everett High School in 1907. According to the Black Heritage Society of Washington State, she went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in education at the UW.

Born in Everett, Manima was the only child of Arminta Spears and Samuel Wilson, a Baptist minister. Her mother and father were married in Canada, but the family lived in Everett, Spokane and Seattle.

Her mother was very active in groups affiliated with the National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Perhaps inspired by her, Manima was involved in a women’s club that ran the former Sojourner Truth Club, a boarding house for at-risk women and their children in Seattle.

“One man who worked at Cascade High School kept track of her after she graduated,” Harrison said. “She went on to study at the University of Washington and worked a lot with a women’s group that created the Sojourner Truth house that used to be up on 19th and Madison. It was still there in 1945.”

She married Claude Davis about 1915 in Ontario. Their three children — Paul, Cathern and Harriett — were born between 1916 and 1920 in Spokane. The family also appears to have lived in Winnepeg for a time.

Wilson died in 1949. She was 63.

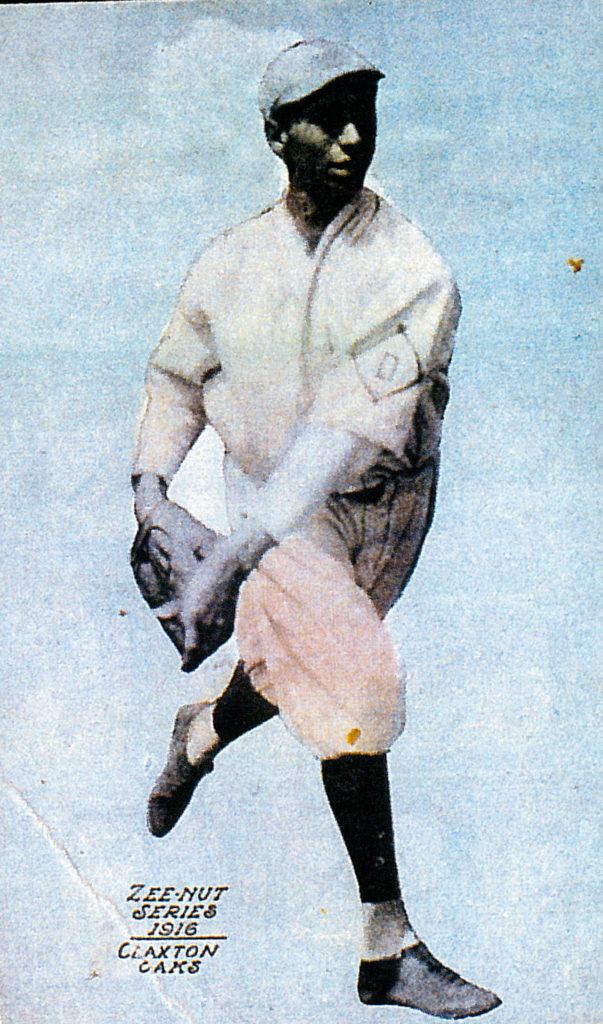

Jimmy Claxton (1892-1970) broke professional baseball’s color barrier 30 years before Jackie Robinson played.

Claxton, who was of mixed racial background, pitched a doubleheader for the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League in 1916 before he was kicked off the team because he was black.

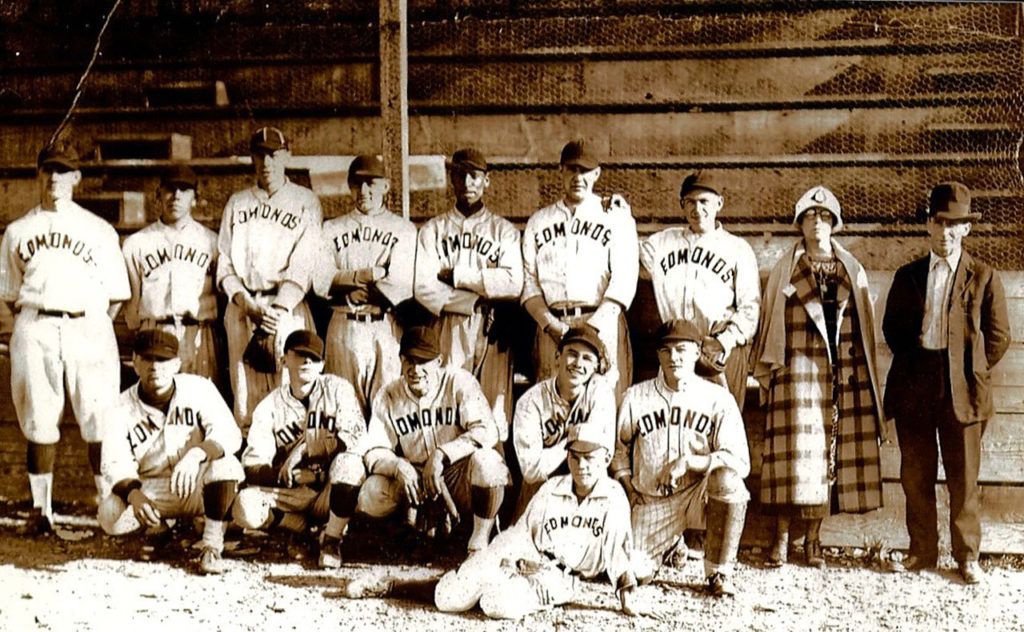

The minor league’s loss became Snohomish County’s gain when he played for the Mukilteo team from 1923-1924 and for the Edmonds team in 1925.

“Everybody knows about Jackie Robinson, and he’s credited with breaking the color barrier, but here we have Jimmy Claxton, the one who really does it decades before,” Mukilteo historian Steven K. Bertrand said. “It was Jimmy’s legacy.”

James Edgar Claxton was born in Wellington, B.C., to a white mother and a father of mostly African-American and Native American heritage.

When he signed with the Oaks, Claxton let the manager believe he was Native American.

Though he never again played professionally, he claimed to have pitched in all but two of the 48 contiguous United States, having never played in Maine or Texas. He was a pitcher for such teams as the Washington Pilots, Chicago Union Giants and Nebraska Indians. He played the sport for more than 50 years.

Claxton also was the first black player to appear on a “Zeenuts” baseball card in 1916. He is on No. 25 of the 143 cards made by the Collins-McCarthy Candy Co. The week he played for Oakland, the candy company’s photographer visited the team.

He was inducted into the Tacoma-Pierce County Sports Hall of Fame in 1969, months before his death. He died in Tacoma at 77.

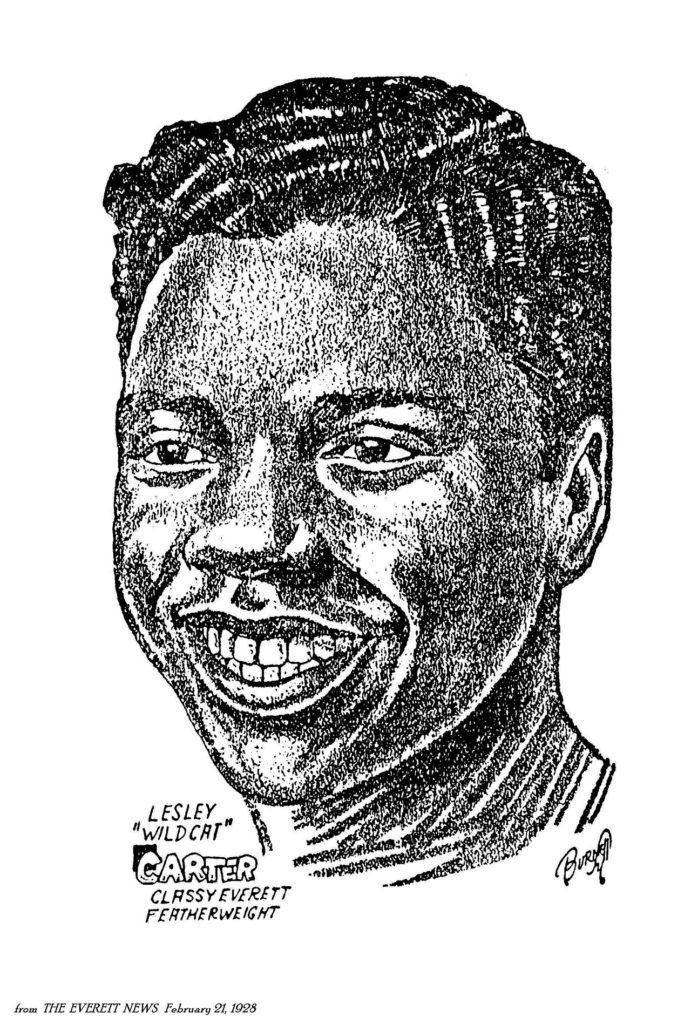

Leslie “Wildcat” Carter (1909-1985) was a popular African-American boxer on the West Coast circa 1925-1936. He and his father moved to Everett from Canada when he was a schoolboy. His mother was reportedly not with them then — though she may have raised their son on an Indian reservation in Oklahoma.

A natural athlete, Leslie Ernest Carter dominated in high school sports and at 14 got into featherweight boxing. He weighed no more than 110 pounds. His first 15 fights in Everett were won with knockouts.

During his boxing career, Carter recorded 137 bouts. He won 79 of those fights and lost 41. Fifteen of them were draws. He had a 29 percent knockout rate throughout his career: While he was only knocked out 12 times, he won 41 fights with knockouts.

“Wildcat was this really frisky, really incredible lightweight boxer,” Dilgard said. “He was a little guy but he was pugnacious. He got into all kinds of adventures.”

Dilgard shared one such adventure: “During the Second World War, a Navy ship was in town for the Fourth of July, and in his day Wildcat was very popular with the ladies. Three sailors saw him with two young white ladies on the street in Everett and attempted to rough him up, but wound up unconscious on the pavement. Wildcat walked away as if there hadn’t been a problem.”

According to a story that ran in The Herald on Feb. 26, 1930, Carter made more than $250,000 in three years.

His then-manager, Joe Waterman, told a reporter that “Carter’s downfall,” when he lost four fights in California, was due to homesickness: Carter couldn’t stand to be away from his wife and two children, even for a short time.

That is likely why Carter didn’t go fight on the East Coast, where he would have been paid a lot more money.

After he retired from boxing, Carter was a maintenance worker at Birmingham Steel in Seattle. He suffered from dementia in his later years and died at 75.

“It’s the sad cliché of a prize fighter with a bad manager making good money really fast based on talent that didn’t really get developed,” Dilgard said. “There was poor career judgment. He had the hell beaten out of him in a few mismatches and wound up working as a janitor.”

Sara Bruestle: 425-339-3046; sbruestle@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @sarabruestle.

Black history celebration

Second Baptist Church, 2801 Virginia Ave., Everett, is hosting an event to celebrate Black History Month at 3 p.m. Feb. 25 that will feature a mass choir, skit and a presentation on notable African-Americans in history. More information is at www.sbceverett.org or call 425-259-6545.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.