Jason Biermann has honored the dead and cared for the living.

Snohomish County’s director of emergency management, Biermann is a veteran of nearly 29 years of military service. Through Army duty, he earned one of the least-awarded identification badges in the U.S. military — second only to the United States Astronaut Badge.

“Honor Guard” say the letters on his badge, its sterling silver worn from being polished daily with jewelers’ rouge.

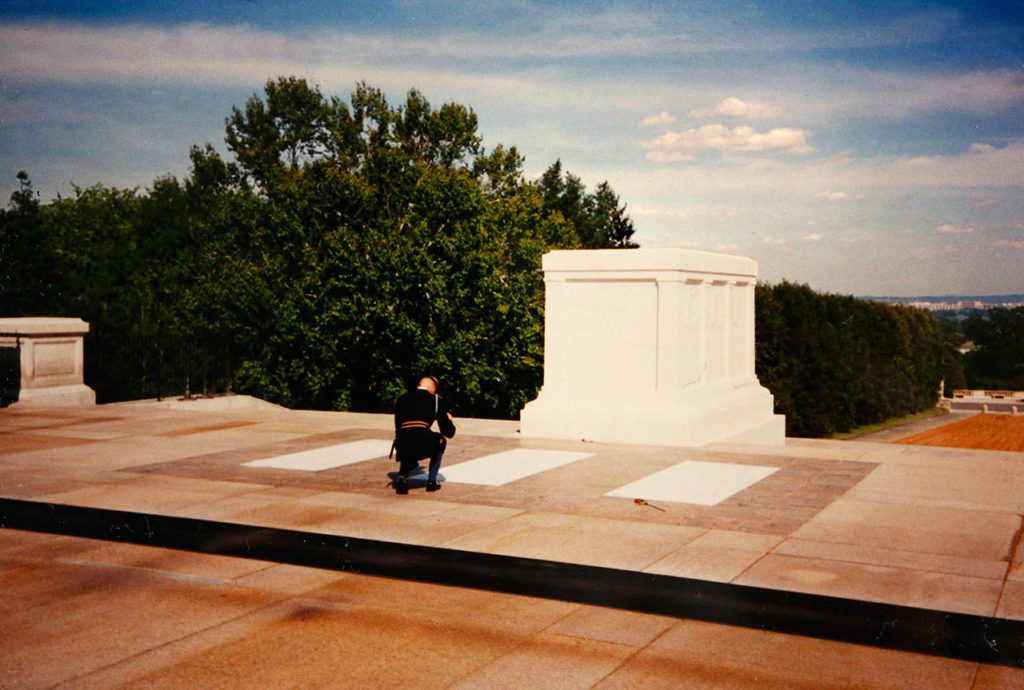

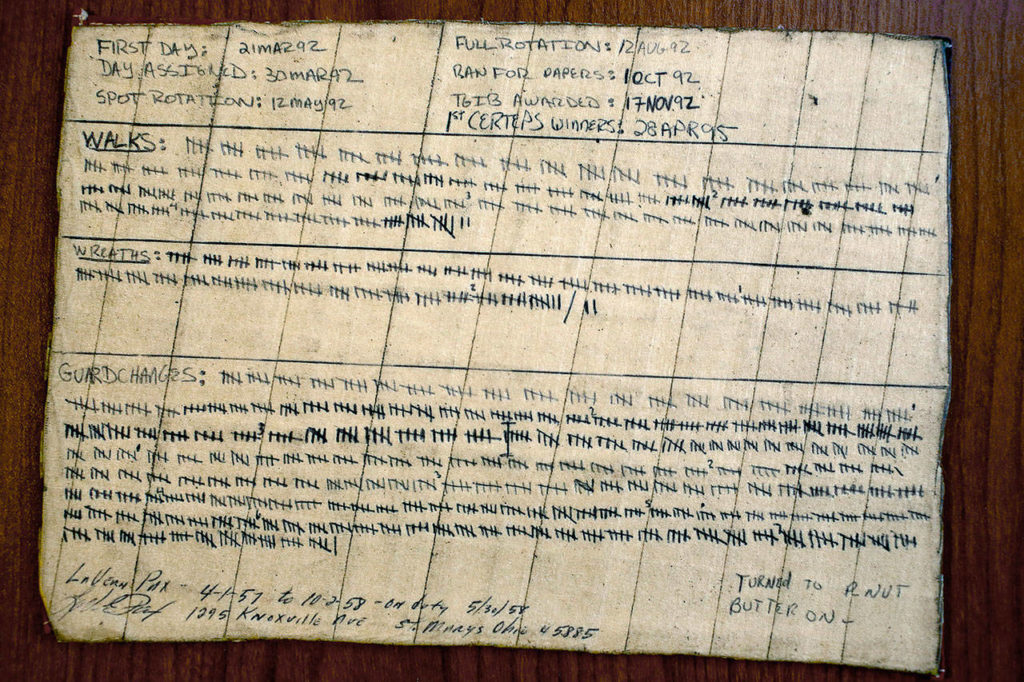

In the early 1990s, Biermann was part of the Honor Guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

A decade later, in 2002, he spent nine months as an Army Reserve medic in Afghanistan.

And a dozen years after that, as a county employee, Biermann managed the emergency operations center after the Oso mudslide.

The duty of a Tomb Guard at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia is somber, precise and steeped in history.

It was Armistice Day 1921 that an unknown American World War I soldier was buried in the plaza of the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington. What was known as the Great War ended Nov. 11, 1918, a century ago.

A sarcophagus, replaced by the current marble tomb in 1926, was above the grave. In 1958, two more unknown Americans were interred in the plaza, one from World War II, the other killed in Korea.

In 1984, an unknown service member from the Vietnam War was interred there. But in 1998, his remains were identified through DNA testing and returned to his family. The marker over what was once the Vietnam crypt is now inscribed with “Honoring and Keeping Faith With America’s Missing Servicemen 1958-1975.”

A Tomb Guard “is sort of the embodiment of people who gave up their identity,” said Biermann, 48, who cited line six of the Sentinel’s Creed: “my standard will remain perfection.”

Biermann’s military career began with financial need, not the pursuit of perfection. He was a student at the University of Iowa when he enlisted in the Army Reserve in 1989. “I needed college money,” he said.

During a two-week stint with the reserve in Washington, D.C., he saw the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns. There and then, Biermann decided that was what he wanted to do. He switched from the Army Reserve to active duty.

Being chosen for the elite Tomb platoon, part of the 3rd U.S. Infantry Regiment known as “The Old Guard,” is a highly selective process. Trainees face strict rules, inspections and knowledge tests that require verbatim memorization of tomb history and the ability to locate — and run to — 150 notable grave sites at Arlington.

“It really is a way to impress on aspiring Tomb Guards the importance of the cemetery,” said Biermann, who earned his badge Nov. 17, 1992, after seven months of training and testing.

Sentinels guard the Tomb of the Unknowns 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, in all weather and under any circumstance. As part of one of three relief groups, a Tomb Guard serves 24 hours on, then 24 off, 24 on, 24 off, 24 on, then four days off. Shifts are a half-hour long in summer, an hour in winter, and there’s work in the Tomb Guard quarters when one is not walking or part of a guard change.

The uniform — wool to hold the creases — must be perfect, with shoes and badge shined. Daytime duty requires sunglasses. Hair is cut every three days.

A Tomb Guard needs an internal stopwatch. They march 21 steps down a black mat, turn and face east for 21 seconds, turn and face north for 21 seconds, then take 21 steps down the mat and repeat. During training, Biermann said, a 10th of a second off meant 21 push-ups.

After the turn, guards switch their M-14 rifles to the shoulder nearest visitors, in a show of defending the tomb from any threat. Is that gun loaded? “I can’t tell you,” Biermann said.

“The hardest thing was getting through training, achieving that standard,” said Biermann, who spent about 30 months as a Tomb Guard, starting when he was 22. “It was time demanding, physically demanding, emotionally demanding. It’s rain or shine. Personal things come up. People get sick.”

In all, he was in the military 28 years and seven months, six and a half years on active duty. He retired from the Army Reserve in April.

Biermann worked as a firefighter in Austin, Texas, and later in emergency management in Teton County, Wyoming.

He was in the Reserve in Texas before the 9/11 attacks in 2001. “A year later I was on a C-130 headed to Afghanistan,” he said.

Biermann shared little about his duty in Afghanistan. “I was there early on, setting up what became a huge operation,” he said. “My group was at Bagram, and partly at Kandahar — all over the place.”

He moved here in 2009, the year he started with Snohomish County’s Emergency Management Department, and became its director in 2016.

On March 22, 2014, he was in Tacoma when his cellphone started ringing. He spent the first week after the Oso mudslide in Darrington. “I slept in Mayor Dan Rankin’s office,” said Biermann, who was at the emergency operations center for a month after the slide that claimed 43 lives. “All those volunteers, it was pretty amazing,” he said.

His Honor Guard badge is No. 388, out of 656 ever awarded. “It’s a small group,” said Biermann, who trained others, including the first female Tomb Guard.

Biermann is also a father, with a daughter and two sons. At 20, his older son is about to graduate from basic training at the Army’s Fort Jackson in South Carolina.

In a life of fatherhood, a military career and a civilian career, his time as a Tomb Guard remains a huge honor. “It’s imprinted on you,” he said.

With every U.S. military member now supplying DNA, Biermann doubts there will ever be another interred at the Tomb of the Unknowns. He spent countless hours there in the presence of three, all recipients of the Medal of Honor. “Here rests in honored glory an American soldier known but to God,” the tomb’s inscription reads.

As a Tomb Guard, said Biermann, “you’re fully aware of the thousands and thousands” of others who gave their lives.

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.