GOLD BAR — For Ralph Wood, it is a simple and important story of forgiveness and reconciliation.

For as long as anyone can remember, a Japanese flag hung on a wall in the Martin-Osterholtz Veterans of Foreign Wars hall in the small eastern Snohomish County town along the Skykomish River. The post received its charter in 1947, but none of the current nine members knew the tale behind the flag, which had found a home among old photos of young men in military uniforms. The assumption has been “a long-gone comrade and veteran of the World War placed it there,” said Wood, 84, a Marine who served in the Korean War.

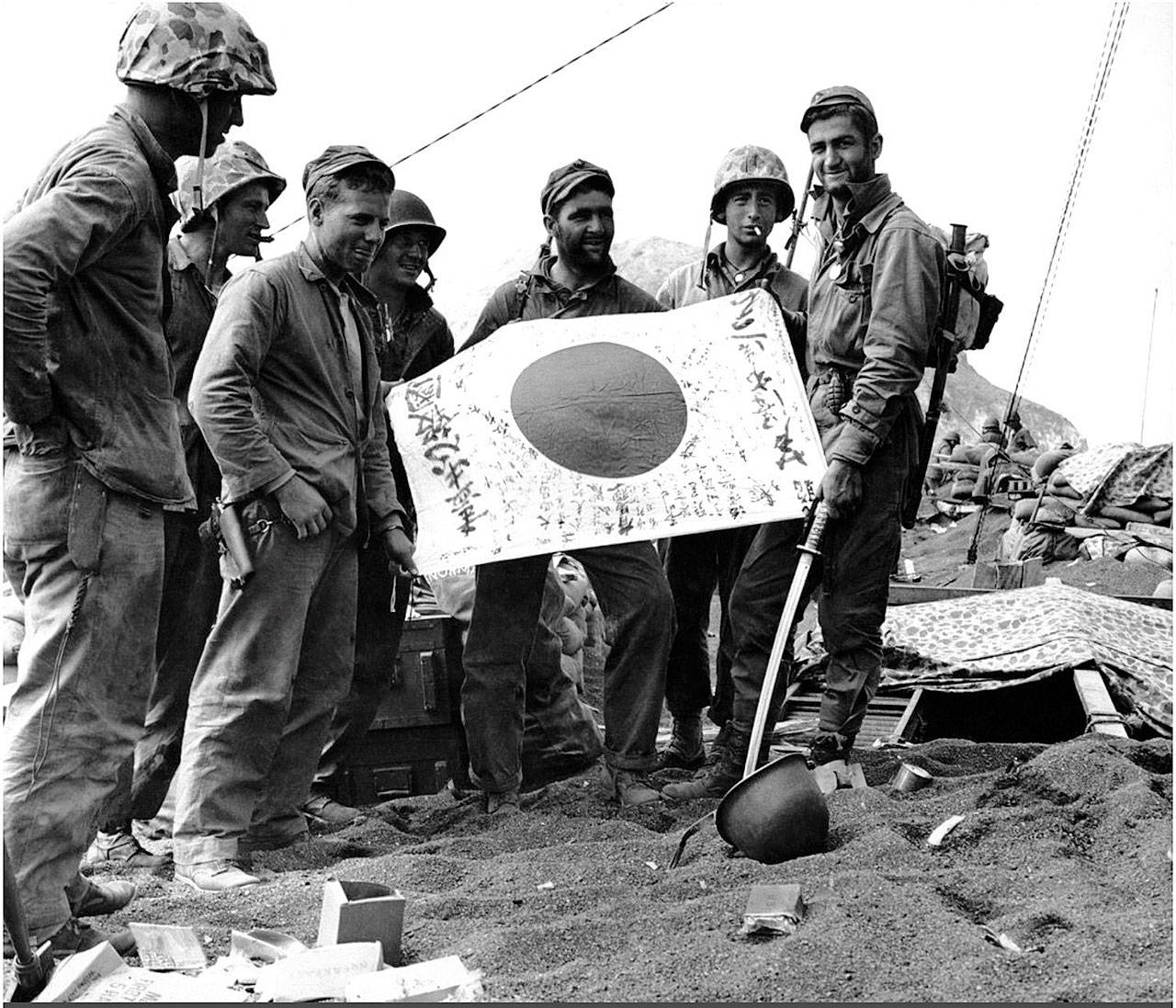

The rectangular cloth has the familiar large red circle depicting the sun in the middle. In the white background that surrounds the crimson orb is Japanese writing made in decorative strokes of black ink. The calligraphy fans out from the center of the flag toward the edges, each stream of symbols written in a different hand. For decades, no one at the post knew what the words meant.

Not until recently, anyway.

In December, Wood happened onto an article about the Obon Society, a resourceful Astoria, Oregon-based nonprofit that returns personal items taken during World War II. It was common among Japanese soldiers to carry Hinomaru national flags signed by friends and family into battle. It also was common for Allied troops to take those flags as keepsakes from the dead, tangible mementos of war and triumph.

The Obon Society was founded by Rex and Keiko Ziak after a flag belonging to her grandfather was returned to her family in 2007. It arrived 62 years after the war and seemingly out of nowhere. Keiko’s mother was too young to remember her father, but the family found relief and happiness to have such a personal connection to him.

“An absolute miracle” is how Keiko Ziak describes it. “It was the strong spirit of grandfather wanting to come home.”

She, in turn, wanted to help reunite other families with similar heirlooms. The undertaking has grown over time. Word has spread across the globe. What began as a trickle has become a steady and at times overwhelming flow of artifacts in various stages of their journey home.

Obon is a Japanese Buddhist custom to honor the spirits of one’s ancestors. It has been observed for more than 500 years and seemed a fitting name to describe the mission. The Obon Society now has more than 30 volunteers, including a network of scholars in Japan. It operates on a shoestring budget through donations and goodwill.

Everyone in the world who cared about a Japanese soldier was represented on the piece of cloth and that makes each flag precious, Rex Ziak said.

The Obon Society has received the long-lost flags from Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, the Marshall Islands, Canada, Mexico, England, Wales, Scotland, Sweden, Netherlands, Portugal, Italy and other far-flung places. In the United States, it has been given items from many sources, including veterans and their families, neighbors and collectors, and from university libraries, museums, high schools and Salvation Army donation centers.

Each relic requires hours of research and careful vetting, genealogical sleuthing and translations back and forth across the Pacific.

The flag at the Gold Bar post was one of the more recent treasures sent to the Obon Society.

Wood shared what he learned with his fellow veterans at the post where members have served in World War II, Korea, Vietnam and the Middle East. In an email to his post commander, Wood wrote: “This strikes me as a righteous thing to do.”

His fellow veterans agreed.

With their blessing, the flag was photographed and later mailed to the Obon Society, which was able to identify the soldier as Masamoto Abe, who was killed Aug. 5, 1944, in New Guinea during World War II.

The society tracked down his nephew, Hisashi Abe, who lives in the Kanagawa prefecture. Volunteers learned that Masamoto Abe was one of six sons. Another son died in Saipan, also in 1944.

The Gold Bar VFW post sent a letter to the friends and relatives of Masamoto Abe.

It read: “… We all have vivid memories of young friends who were killed while doing what they felt was their duty: serving their country. We sometimes wonder who else is remembering them and the life they never got to live. We are very pleased to know that this flag is being returned to its place of origin and into the custody of those who knew and honored the man who carried it into battle.”

Keiko once thought that it was only the families in Japan who benefited from the flags’ return. Neighbors and relatives over weeks and months often will visit the homes where the flags are sent. Word ripples out, giving hope to others who lost relatives in World War II that they, too, might experience a similar reconnection to a loved one.

Rex and Keiko also have learned the act of returning a flag can be satisfying and even heartwarming for Americans, especially veterans and their families.

“It sends a powerful message, like an olive branch, even 73 years later,” Rex said. “We know it heals on both sides of the ocean.”

The Obon Society has received more than 1,000 items over the years, and so far has reunited more than 200 with families.

The Gold Bar flag proved unique.

It is the second flag being returned to the same family in Japan.

The Gold Bar flag had been photographed and catalogued into the Obon Society database and was awaiting the search.

By chance a summer intern was organizing old files and scanning paperwork while Keiko Ziak was reviewing the Gold Bar paperwork. When she glanced at an old file stacked by a scanner, she noticed a familiar name. The flag appeared to have belonged to Masamoto Abe.

“Our scholars in Japan did an expedited search and, to our complete surprise, traced the Gold Bar flag to the exact same Abe family,” Rex Ziak said. “Our associates in Japan contacted the Abe family and sent them several photographs of the Gold Bar flag … and not only did they confirm the name of the soldier, but they noticed many other signatures on the flag as belonging to people who are neighboring families that continue to live in their neighborhood.”

The Gold Bar flag had been given to Abe by his immediate family; the other flag was apparently from co-workers at a factory called Japan Carbon Industrial where Abe worked before he was drafted. The first flag had been given to the Obon Society by a man living in Portland whose father had served in the U.S. Army’s 41st Infantry Division, which was involved in fighting in New Guinea during the time Abe was killed. That search required more than 15 months to trace back to his family.

In a thank-you letter in 2016, Hisashi and Saeko Abe, the soldier’s nephew and his wife, expressed their gratitude.

“I believe my Uncle Masamoto is also happy to finally return to home,” the letter said in English.

Someday, the Gold Bar VFW might get a similar note, which likely will find a home in the same hall where the Abe flag once hung.

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.