Paul Bochan was an immigrant who loved America. He was a U.S. Army veteran who served during the Korean War. A native of Poland, in World War II he was held by the Nazis at Dachau, a concentration camp in Germany.

His widow, Jean Bochan, is the keeper of his memories.

She lives in the rural Snohomish home they shared. Her husband was 85 when he died in 2011. They had been married 54 years.

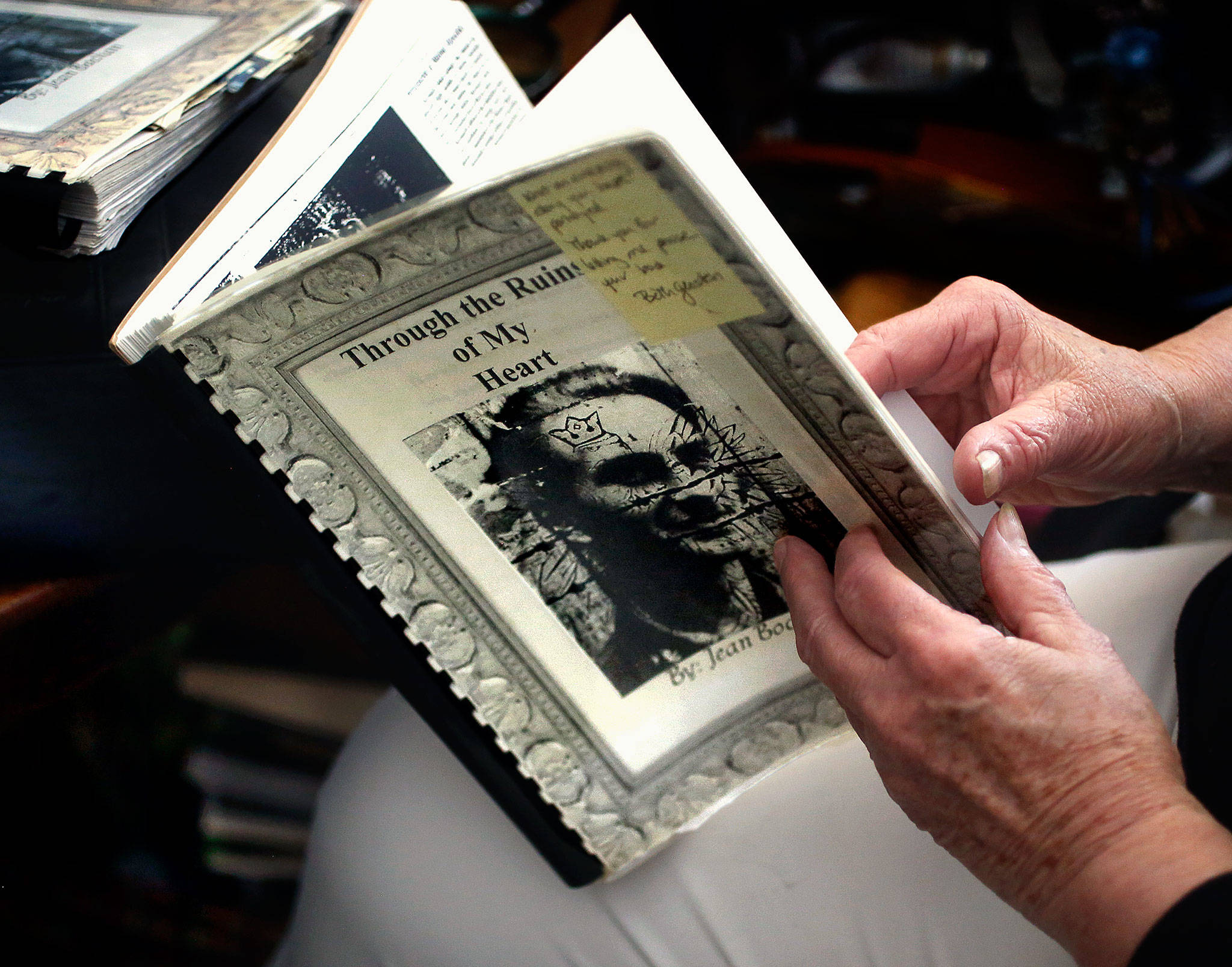

From stories her husband shared — along with his documents, photos and news clippings — Jean Bochan wrote a collection of poems. Compiled in her self-published book “Through the Ruins of My Heart,” it’s a lyrical story of Paul Bochan’s life.

“It’s history. He lived it, as a refugee and an immigrant,” she said Wednesday.

Jean Bochan, 79, called last week with a word of thanks. She wanted to express gratitude to Dick Nelms. A 95-year-old former B-17 pilot, Nelms flew 35 bombing missions over Germany in 1944. Featured in this column a week ago, Nelms was an honored speaker for a May 17 gathering at the Stanwood Eagles hall.

Bochan recalled her late husband sharing memories of seeing the Americans’ B-17s overhead — and praying for them — during his time of forced labor and imprisonment at Dachau.

Her house, where she does leather tooling work on saddles, is filled with mementos of Paul Bochan’s life. He came to the United States, through Ellis Island, as a refugee in 1949. After the war, he refused to return to a communist Poland and spent several years in displaced-person camps in Europe.

Documents show he was sponsored in the United States by “Mr. and Mrs. Nick Eliason, Seattle.” The sponsorship was organized by a Seattle priest as part of the National Catholic Welfare Conference’s War Relief Services.

Jean was 18 and Paul was 31 when they married in 1957. By then, he was working for a Seattle business that made prostheses and braces. Many of those needing his handiwork had suffered from polio. Jean met him when she took a job as a secretary at the business.

His skills in prosthetics were developed during the Korean War. Drafted into the U.S. Army at 26, he was based at Ford Ord in California. He was also part of a medical training group at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. Jean Bochan said her husband was considered an “atomic veteran” who witnessed nuclear testing at Yucca Flat, Nevada.

He was a corporal when he left the military in 1953.

In Jean’s book is a 1953 letter of commendation, written by Lt. Col. Lloyd Taylor at Fitzsimons Army Hospital in Colorado. It praised Bochan’s “outstanding performance” and said he would be “extremely difficult” to replace.

Paul Bochan did not share his concentration camp experiences until late in life, his widow said. He wasn’t Jewish, but was involved in the Polish resistance during the Nazi occupation.

He was first held at Lukiskes Prison, in Vilnius, Lithuania, a place used by the Nazi Gestapo to imprison Jews along with others for their actions with the resistance. From Lithuania, Bochan told his wife, he was sent by cattle car to Dachau in southern Germany. Dachau was not an extermination camp, like Auschwitz in Poland was, but tens of thousands died there.

Paul Bochan, who had told Jean about being lice-ridden and subsisting on potato-peel soup, was photographed with other emaciated people when Dachau was liberated by American soldiers on April 29, 1945. He was among some 32,000 Dachau prisoners who lived to see that day.

In the final pages of Jean’s book is evidence of Bochan’s forced labor at the hands of the Nazis.

She included an Associated Press article, dated March 24, 2000, about a $5 billion German fund to compensate aging victims of Nazi-era forced labor. Paul Bochan, at one point, had been forced to work in a coal mine.

There’s a photocopy of a $1,166 check in Jean’s book. It’s made out to Paul Bochan, ordered by the Swiss-based International Organization for Migration, as part of “German Forced Labour Compensation.” The check, dated May 30, 2002, and sent to Bochan’s Snohomish address, was an installment on his total award — $5,000.

A few pages before the image of that check is one of Jean’s poems, titled “Stolen Years.”

“Why did my war life story get written after so many years?” it asks. And the poem ends, “The chapter is closing on those who committed the war crimes.”

There were other chapters in Paul Bochan’s life. Together, he and his wife raised a daughter and a son. They were involved in horse training. His career included creating a brace for an injured UW Husky football player. It’s all in his wife’s book.

Her husband learned English, but always spoke with a Polish accent. And she learned a few Polish phrases, among them “I love you very much, my beloved.”

Jean Bochan thinks now of today’s refugees, from Syria and other war-torn places. “Nobody wants them. It’s tragic,” she said.

And she remembers her husband’s deep love of the country he chose as his own.

“The magic of Americans would stay with him the rest of his life,” she said.

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@herald net.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.