By Peniel E. Joseph / The Washington Post

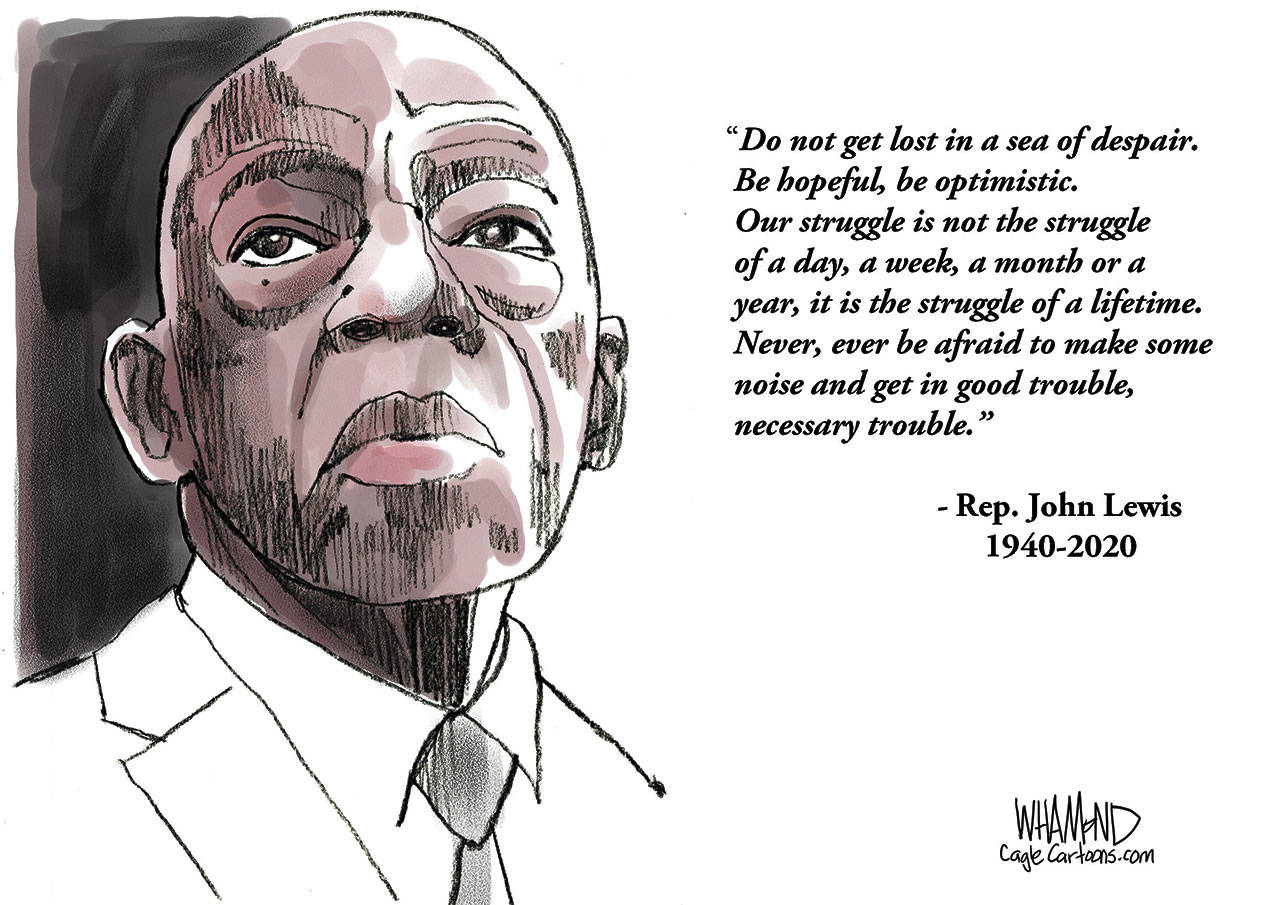

On July 17, congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis died at 80 on the same day as 95-year-old stalwart C.T. Vivian, Martin Luther King’s favorite preacher. Both leave behind a legacy of social justice activism that played a pivotal role in some of the most resounding victories of the civil rights movement: America’s Second Reconstruction.

Lewis’ death comes at a critical moment in U.S. history amid a moral and political reckoning on black dignity and citizenship that represents nothing less than a Third American Reconstruction. And his life provides lessons for activists today on how to confront racial violence, forge productive alliances and transform American democracy.

Born in 1940 in Troy, Ala., to a family of sharecropping farmers, the deeply religious Lewis joined the movement for black dignity and citizenship as a student activist in Nashville. Already enthralled by the dazzling oratory of the young Martin Luther King Jr., Lewis enjoyed an unusual kind of political apprenticeship under the mentorship of an array of movement leaders. He learned the practical application of nonviolent civil disobedience from the Rev. James Lawson and became fast friends with fellow student activists such as Diane Nash. Ella Baker, the founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”), played a critical role in convincing students such as Lewis that they — and not just King and older generations of preachers — could play pivotal leadership roles in an unfolding national drama.

Lewis’ calm demeanor, personal sincerity and outward humility made him a quiet star among student leaders. He was arrested dozens of times for civil rights activism between 1960 and 1966. In 1961, he joined hundreds of volunteers on Freedom Rides, traveling throughout the Jim Crow South to challenge segregated bus terminals. On May 14, 1961, Lewis experienced a vicious beating at the hands of a white mob as a Freedom Rider in Anniston, Ala. It was the first of many brutal experiences he endured as an activist, and such punishment bolstered Lewis’s political resolve to defeat racial segregation.

Elected chairman of SNCC in 1963, Lewis became the youngest national civil rights leader of the 1960s. At only 23, he was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. Although parts of the collectively written speech were abandoned after objections from white allies in the movement, Lewis prepared the nation for continued racial combat in the service of justice. “By the force of our demands, our determination and our numbers, we shall splinter the desegregated South into a thousand pieces and pull them back together in the image of God and democracy,” he argued.

Lewis effectively navigated between student militants in SNCC — which craved transformational political change radical enough to protect black life in the Mississippi Delta and Alabama black belt — and more pragmatic civil rights leaders who viewed the Democratic Party as the most effective vehicle for widespread social change. In 1964, Lewis encountered Malcolm X while touring Africa in hopes of forging international alliances to strengthen domestic black freedom struggles and came away from his meeting impressed with the black nationalist icon’s willingness to explore political alliances with civil rights leaders.

On March 7, 1965, Lewis, dressed in a crisp white shirt, tie, raincoat and backpack, joined several hundred demonstrators crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., who were routed by blue-helmeted state troopers. The violence that afternoon left Lewis with permanent scars on his head. But the activists’ resolve in the face of violent opposition helped trigger the moral and political outrage that led to the passage of voting rights legislation. Lewis’ involvement at that moment made visible to the whole nation the violent, racist dehumanization of black people.

In May 1966, Stokely Carmichael, the charismatic Howard University activist and friend-turned-organizational rival, replaced Lewis as SNCC chairman. Carmichael’s call for “Black Power!” the next month during a civil rights demonstration in Mississippi helped to transform the aesthetics of the black freedom struggle. Lewis completed his college degree at Fisk University at the moment when Black Power activists were calling for a dramatic and radical restructuring of American democracy. The political vision of Black Power activists, despite political disagreements with Carmichael and SNCC, inspired Lewis, who used the racial solidarity forged in the crucible of the movement as a springboard to political office.

As the radical hopes of the 1960s faded in the aftermath of King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, Lewis turned to electoral politics. In 1986, he won the Georgia congressional seat he would hold until his death in an ugly political battle with Julian Bond, the charismatic SNCC activist and former-friend-turned-bitter-adversary. Over the next 33 years, Lewis went from staring down the forces of white supremacy at bus stations and bridges to confronting these same adversaries in the U.S. Congress. Bringing organizing skills learned as an activist and radical ideas about transforming American life, he fought valiantly for health-care, gun-control and anti-poverty legislation. During the late 1980s and 1990s as the nation turned away from the vision of the “Beloved Community” outlined at the March on Washington, Lewis advocated for a return to the anti-poverty and anti-racist policies that briefly flourished during the 1960s.

The American political establishment, over time, caught up with his accomplishments. Barack Obama’s watershed presidential election proved a boon to Lewis’s political legacy, with the first black president acknowledging the congressman’s towering achievements with a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Lewis recognized Obama’s ascent as a part of a political harvest reaped from the bloodstained sacrifices of earlier generations.

Lewis understood that those struggles for black dignity and citizenship continued during his lifetime. He embraced the Black Lives Matter movement, including the recent national and global protests for racial justice and equality in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder at the hands of police. “It is so much more massive and all-inclusive,” Lewis noted of Black Lives Matter. Whereas black women, including those who helped to nurture Lewis and lead the movement, were excluded from speaking at the March on Washington in 1963, he marveled to witness the prominence of black women in the BLM movement; as featured leaders, organizers and strategists. As an elder statesman within political and civil rights circles, Lewis continued to encourage the young to lead a movement he recognized as continuing into our own time.

Lewis’s extraordinary life offers important lessons for contemporary generations organizing for black equality in America and around the world. His example teaches us that movements for racial justice have always been denigrated by authorities and been targets of violence by political, legislative and military bodies. Young people who refused to heed the warnings of an older generation helped to transform American democracy, but they received crucial mentoring from a council of elders who believed, like Baker, that strong people did not require charismatic top-down patriarchal leadership. To the contrary, young activists could be trusted to ask the right questions that would lead to what Lewis called the “good trouble” capable of ending systemic racism, structural violence and white supremacy.

Peniel E. Joseph is the Barbara Jordan chair in ethics and political values at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. He also is the founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. His latest book is”The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.