By Emily Vraga

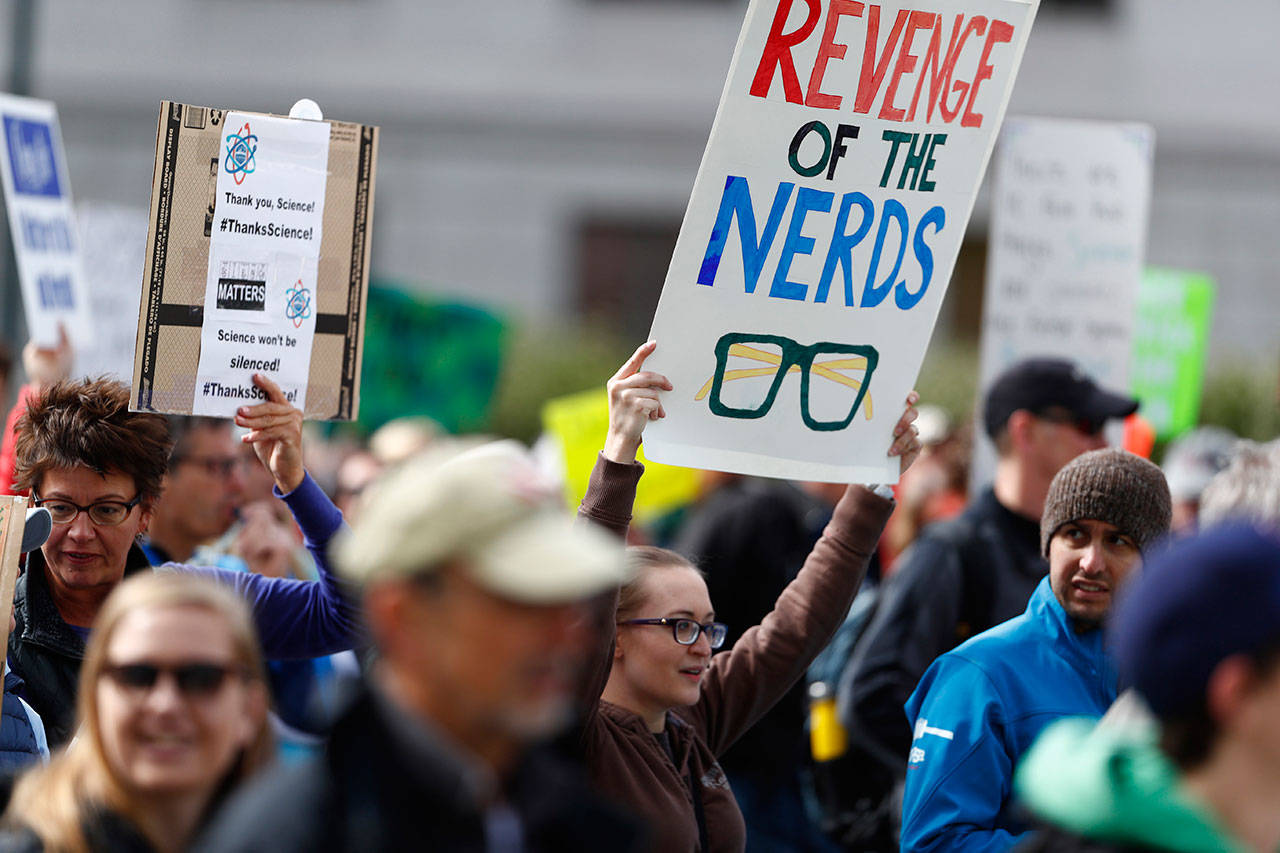

Following Saturday’s March for Science, questions about whether scientists can and should advocate for public policy become more important.

On one hand, scientists have relevant expertise to contribute to conversations about public policy. And in the abstract, the American public supports the idea that scientists should be involved in political debate. On the other hand, scientists who advocate may risk losing the trust of the public. Maintaining that trust is imperative for scientists, both to be able to communicate public risks appropriately and to preserve public funding for research.

Little existing research had tested how audiences react when confronted with concrete examples of scientific advocacy. Led by my colleague John Kotcher, my colleagues and I at the George Mason Center for Climate Change Communication devised an experiment to test these questions in the summer of 2014. Our results suggest there is at least some tolerance for advocacy by scientists among the American public.

Testing a scientist’s perceived credibility: We asked more than 1,200 American adults to read the biography and a single Facebook post of a (fictional) climate scientist named Dr. Dave Wilson. In this post, Dr. Wilson promotes his recent interview regarding his work on climate change. We varied the message of this statement to include a range of advocacy messages — from no advocacy (discussing recent evidence about climate change) to clear advocacy for specific policies to address climate change.

We found that perceptions of Dr. Wilson’s credibility — and of the scientific community more broadly — did not noticeably decline when he engaged in most types of advocacy.

When Dr. Wilson championed taking action on climate change, without specifying what action, he was considered equally credible as when he described new evidence on climate change or discussed the risks and benefits of a range of policies. In fact, perceptions of Dr. Wilson’s credibility were maintained even when he argued in favor of reducing carbon emissions at coal-fired power plants.

Only when Dr. Wilson advocated for building more nuclear power plants did his credibility suffer.

Advocacy received differently than partisanship: Our study suggests that the American public may not see scientists who advocate for general action on scientific issues as lacking in credibility, nor will they punish the scientific community for one scientist’s advocacy. Yet this study represented only one case of scientific advocacy; other forms of advocacy may not be as accepted by the public. For example, more caution is required when scientists promote specific (unpopular) policies.

Most notably, our study did not test overtly partisan statements from Dr. Wilson. Our research participants saw it that way too; they rated all of Dr. Wilson’s statements as more scientific than political.

The March for Science, however, does risk being seen as motivated by partisan beliefs. In that case, scientists may not escape being criticized for their actions. This is especially true if the march is seen as a protest against President Trump or Republicans in general. In our study, conservatives saw Dr. Wilson as less credible whether he engaged in advocacy or not. If conservatives see the march as a protest against their values, they may dismiss the message of the march — and the messengers — without considering its merits.

This risk is exacerbated when media coverage of the March for Science is considered. In our study, people saw Dr. Wilson promoting his interview in his Facebook post, but were not exposed to the actual interview in which Dr. Wilson made his case for a given policy. Nor were his actions disruptive; a single post on social media is relatively easy to skip or ignore, and Dr. Wilson could frame his interview in the way he liked.

The March for Science will be the opposite. If successful, the march will garner attention from news outlets, who may reframe the purpose of the march.

Balancing the advocacy message: So what can be done to limit accusations of partisan bias surrounding the march?

One way marchers can minimize this possibility is by crafting an inclusive message that resonates with many people, stressing the ways science improves our society and protects future generations. However, the march’s similarity to other explicitly anti-Trump marches may make it hard to avoid a partisan connotation.

Moreover, in our research Dr. Wilson was portrayed as an older white male, matching cultural stereotypes about scientists; he may have had more freedom to engage in advocacy than would female or nonwhite scientists. An inclusive and diverse March for Science may challenge these traditional portrayals of scientists. While many (the authors included) would see that as a desirable objective in itself, it may complicate successful advocacy.

A goal of the March for Science is to demonstrate that science is a nonpartisan issue. It represents a unique opportunity for scientists to highlight the ways in which science improves our society. Scientists participating in the march should emphasize shared values with those who might otherwise disagree — such as the desire to create a better world for our children and grandchildren.

If the event remains a March for Science, rather than a march against a party or group, the chances increase that it will effectively focus attention on the importance of scientific research.

Emily Vraga is an assistant professor at George Mason University’s Department of Communication. This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.