By Jay L. Zagorsky

For The Conversation

U.S. roads and bridges are in abysmal shape, and that was before the recent winter storms made things even worse.

In fact, the government rates over one-quarter of all urban interstates as in fair to poor condition, and one-third of U.S. bridges need repair.

To fix the potholes and crumbling roads, federal, state and local governments rely on fuel taxes, which raise more than $80 billion a year and pay for around three-quarters of what the U.S. spends on building new roads and maintaining them.

I recently purchased an electric car, the Tesla Model 3. While swerving down a particularly rutted highway in New York, the economist in me began to wonder, what will happen to the roads as fewer and fewer cars run on gasoline? Who will pay to fix the streets?

Fuel taxes 101: Every time you go to the pump, each gallon of fuel you purchase puts money into a variety of pockets.

About half goes to the drillers that extract oil from the earth. Just under a quarter pays the refineries to turn crude into gasoline. And around 6 percent goes to distributors.

The rest, or typically about 20 percent of every gallon of gas, goes to various governments to maintain and enhance the U.S. transportation’s infrastructure.

Currently, the federal government charges 18.4 cents per gallon of gasoline, which provides 85 percent to 90 percent of the Highway Trust Fund that finances most federal spending on highways and mass transit.

State and local government charge their own taxes that vary widely. Combined with the national levy, fuel taxes range from more than 70 cents per gallon in high-tax states like California and Pennsylvania to a little more than 30 cents in states like Alaska and Arizona. The difference is a key reason the price of gasoline changes so dramatically when you cross state lines.

While people often complain when their fuel prices go up, the real burden of gasoline taxes has been falling for decades. The federal government’s 18.4 cent tax, for example, was set way back in 1993. The tax would have to be 73 percent higher, or 32 cents, to have the same purchasing power.

On top of that, today’s vehicles get better mileage, which means fewer gallons of gas and less money collected in taxes.

And plug-in electric vehicles, of course, don’t need gasoline, so their drivers don’t pay a dime in fuel taxes.

A crisis in the making: At the moment, this doesn’t present a crisis because electric vehicles represent only a small proportion of the U.S. fleet.

Slightly more than 1 million plug-in vehicles have been sold since 2012 when the first mass market models hit the roads. While impressive, that figure is just a fraction of the more than 250 million vehicles currently registered and legally drivable on U.S. highways.

But sales of electric cars are growing rapidly as how far they can travel before recharging climbs and prices fall. Dealers sold a record 360,000 electric vehicles last year, up 80 percent from 2017.

If sales continue at this breakneck pace, electric cars will become mainstream in no time. In addition, governments in Europe and China are actively steering consumers away from fossil fuels and toward their electric counterparts.

In other words, the time will come very soon when the U.S. and individual states will no longer be able to rely on fuel taxes to mend American roads.

Some states are already anticipating this eventuality and are crafting solutions.

One involves charging owners of electric cars a fixed fee. So far, 17 states have done just that, with annual taxes ranging from $100 to $200 per car.

There are a few of problems with a fixed-fee approach. For example, the proceeds only go to state coffers, even though the driver also uses out-of-state roads and national highways.

Another is that it’s regressive. Since a fixed fee hits all owners equally, regardless of income or how much they drive, it hurts poorer consumers most. During debate in Maine over a proposed $250 annual EV fee, opponents noted that the average person currently pays just a third of that — $82 — in state fuel taxes.

Oregon is testing another solution. Instead of paying fuel taxes, drivers are able to volunteer for a program that lets them pay based on miles driven rather than how many gallons they consume. The state installs tracking devices in their cars — whether electric or conventional — and drivers get a refund for the gas tax they pay at the pump.

The program raises privacy and fairness concerns especially for rural residents who have few other transportation options.

Another way forward: I believe there’s another solution.

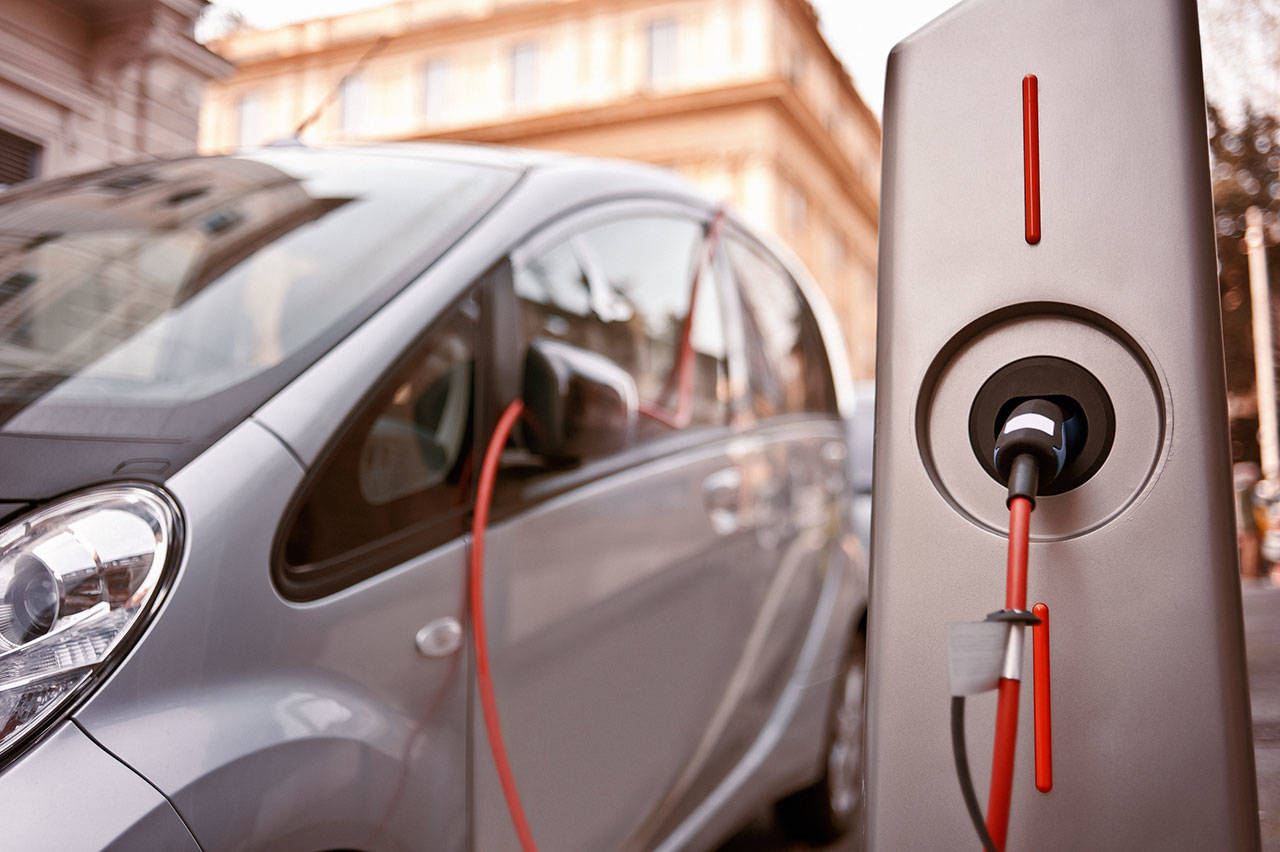

Currently, carmakers and others are deploying large networks of charging stations throughout the country. Examples include Tesla’s Superchargers, Chargepoint, EVgo and Volkswagen’s proposed mobile chargers.

They operate just like gas pumps, only they provide kilowatts of electricity instead of gallons of fuel. While electric vehicle owners are free to use their own power outlets, anyone traveling long distances has to use these stations. And because charging at home is a hassle — requiring eight to 20 hours — I believe most drivers will increasingly choose the convenience and speed of the charging stations, which can fill up an EV in as little as 30 minutes.

So one option could be for governments to tack on their taxes to the bill, charging a few extra cents per kilowatt “pumped into the tank.” Furthermore, I would argue that the tax — whether on fuel or power — shouldn’t be a fixed amount but a percentage, which makes it less likely to be eroded by inflation over time.

It is in everyone’s interest to ensure there are funds to maintain the nation’s road. A small percentage tax on EV charging stations will help maintain U.S. roads without hurting electric vehicles’ chances of becoming a mass market product.

Jay L. Zagorsky is a lecturer at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.