EDMONDS — A Swiss couple was paddling all the way to Ketchikan, Alaska. A student about to start college was planning to arrive in Bellingham over water. Another woman, who had spent the last 438 days circumnavigating the lower 48 states by bike and kayak, scribbled her note on the last leg of her journey.

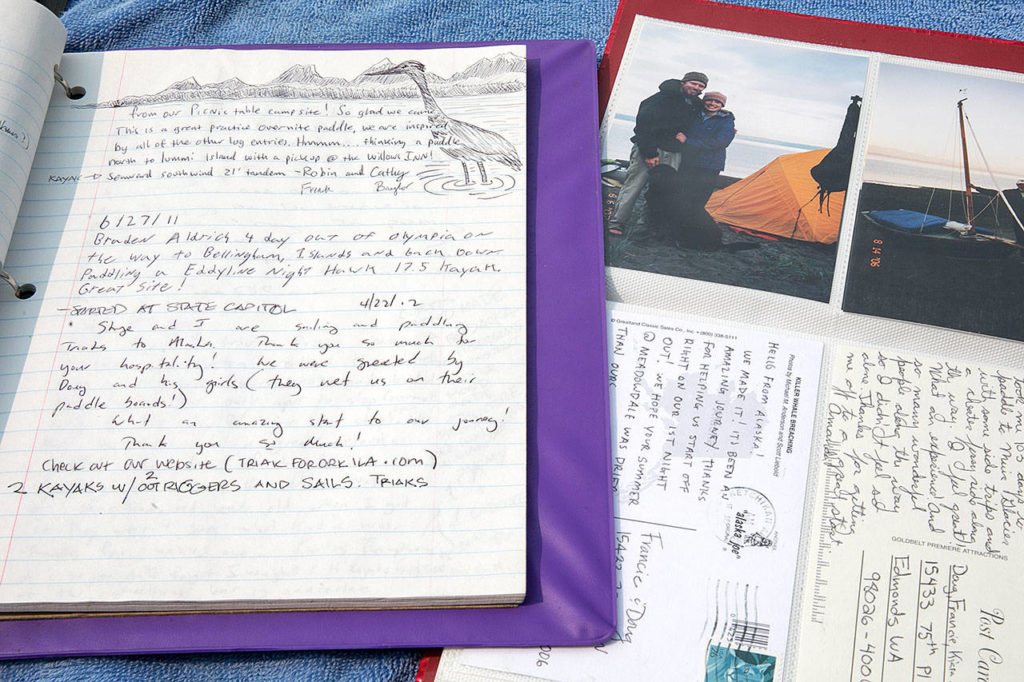

A group of five was caught in a downpour as they left Seattle on the first day of traveling to Vancouver, B.C., as part of a charity trip for muscular dystrophy. And a solo paddler from Duvall in a rented kayak had embarked on his first long-distance expedition. “Never did more than 12 miles prior to the trip,” he wrote in a communal journal that documents those who arrived over water to Meadowdale Beach Park in Edmonds.

“Each one is a different story,” said Doug Dailer, the ranger at the park, thumbing through the memories recorded in a notebook in a purple binder.

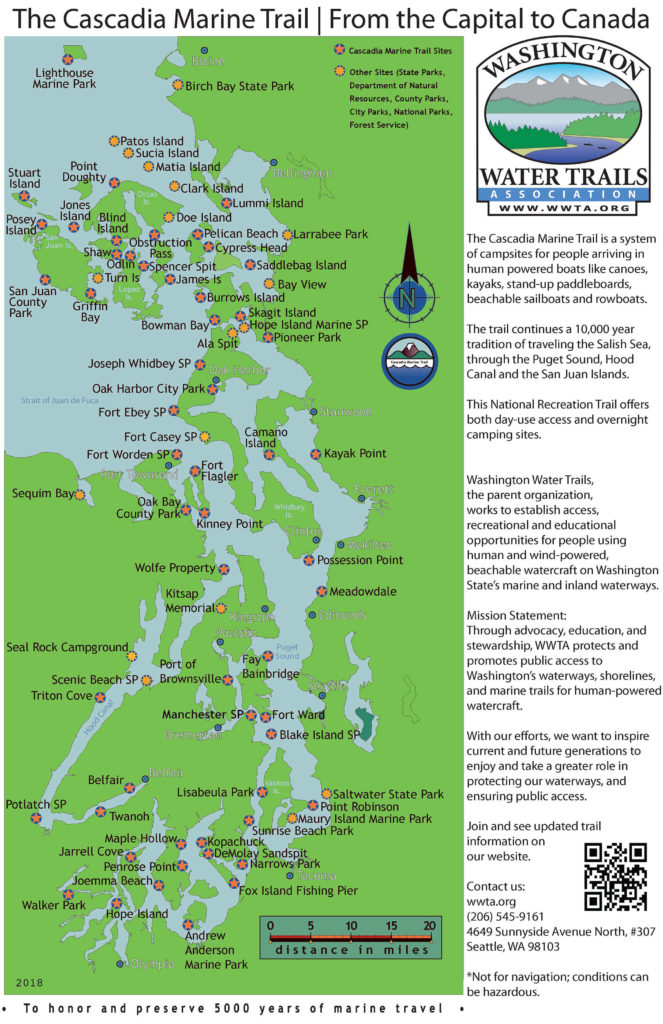

The entries, which begin in 1998, are from people traveling the Cascadia Marine Trail. The route meanders along more than 2,300 miles of the Puget Sound shoreline stretching from Olympia to Canada.

The trail was established in 1993, after members of the Washington Water Trails Association began to notice access to the sound was dwindling as development and population growth consumed prized land along the shoreline. The Cascadia Marine Trail has since grown to 66 campsites and more than 150 day-use stops.

The association wants to find a site every five to eight miles along the route, to ensure the shoreline and waterways remain within reach of the public.

The Cascadia Marine Trail, where paddles rhythmically dip into the water as ospreys plunge for fish and crabs scurry below, aims to honor and preserve the long tradition of marine travel through the Salish Sea.

Preserving access

When Tom Steinburn and Tom Deschner, along with other founders of the trail, paddled around Puget Sound in the late 1970s, they were surrounded by beaches where kayakers could come ashore for lunch or to pitch a tent for the night.

As the state’s population grew, owners of large farms and homesteads subdivided their land into smaller and smaller pieces. And Steinburn and Deschner began seeing no trespassing signs along the shore, said Reed Waite, executive director of the Washington Water Trails Association between 2000 and 2008.

“They would come to a beach they had been before and a house was now perched there,” Waite said. “They saw their recreational opportunities disappearing.”

Shortly after the trail was designated, Steinburn, who has since passed away, told the Kitsap Sun, “If something wasn’t done, all of the richness of Puget Sound would be lost to people who, for a modest outlay, could get out and enjoy it.”

The association decided a system of dedicated access points and campsites was needed to keep paddlers, or any human- or wind-powered craft, exploring the water.

“Finding a place to safe harbor is important,” said Don Crook, the vice president.

Weather can rapidly shift, or strong currents can force a change of plans.

Without campsites, Crook said, “there would be a lot of commando (illegal) camping.”

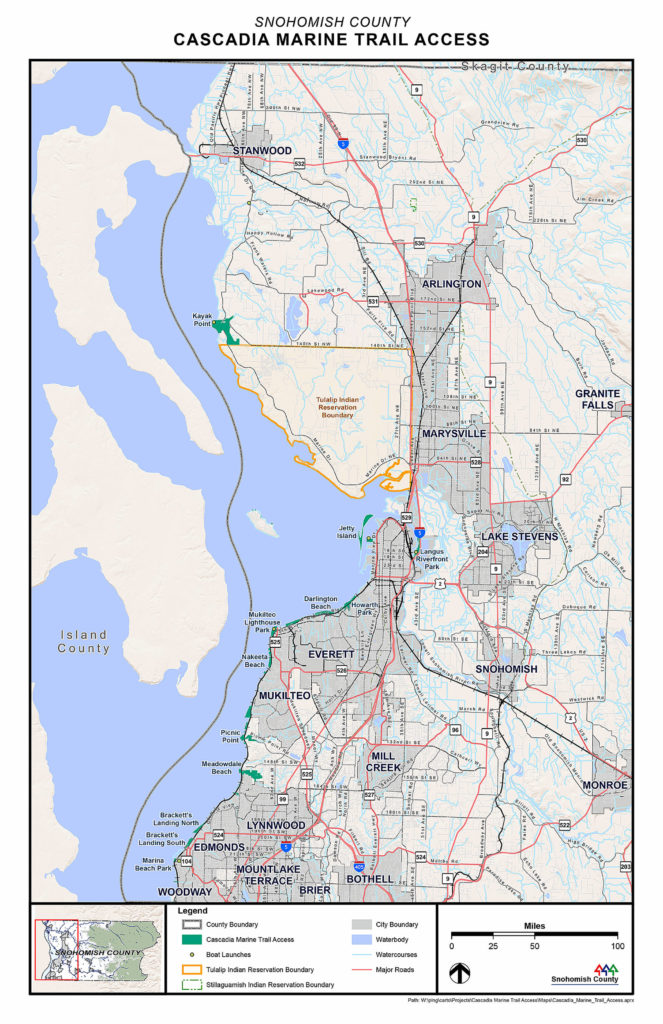

Snohomish County has two official Cascadia Marine Trail sites, and both allow camping: Kayak Point and Meadowdale Beach Park. According to the county, there are four boat launch sites, including Kayak Point near Stanwood, and about a dozen day-use spots.

A 2013 inventory of Puget Sound found about 19 percent of the shoreline was public. But with rocky bluffs along much of the region’s coast, only about half of that is actually reachable.

“Therefore, the public has real access to about 10 percent of the inland marine waters of Puget Sound,” according to the report by the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit conservation group.

“As our population grows, the pressure on existing facilities is acute and the need for new, accessible public spaces is urgent,” the report said.

With about a quarter of publicly owned shoreline along Puget Sound, Snohomish County has a larger percentage than many of the other 12 counties that line the inlet.

Over the last two decades or so, the amount of publicly accessible shoreline in the county hasn’t changed much, said Joshua Dugan with the county executive’s office.

Waite said Washington state, unlike California and Oregon, didn’t pass policies to ensure land along the water remains in the public domain.

Washington took a different approach to shoreline management, said Curt Hart, a spokesman for the state Department of Ecology.

The state requires local jurisdictions to develop a shoreline master program to protect the land and ensure the public has access, he said. The department works with cities and counties to prevent the loss of public access points and add new spots.

“It doesn’t say that every shoreline is open to the public,” he said.

That’s different from Oregon’s law, which established public ownership along the coast from the water to 16 vertical feet above the low tide mark.

“It’s something we hold in common and nobody should have domain over it,” Waite said.

Private landowners in Washington own the shore and the tidelands, he said. “And people are pretty selfish with their shellfish.”

Possibilities are limitless

The hazy, smoky August skies weighed heavy as Don Crook and Andrée Hurley launched their kayaks from Snee Oosh Beach on the Swinomish Reservation near La Conner.

Hurley, president of the Washington Water Trails Association, spent her childhood along the ocean and has led kayak expeditions in Puget Sound for years. Crook started kayaking in Lake Michigan when he lived outside Chicago.

Launching at low tide forced the pair to wade through thick mud that sucks shoes and feet deep into the slime. Eagles soared overhead and harbor seals emerged from the water for a better look as the kayakers aimed for Hope Island State Park, one of the stops on the Cascadia Marine Trail.

Many of the marine trail sites are reserved only for people arriving by boat that is powered by humans or wind. At some sites, including Meadowdale Beach Park, paddlers are the only campers allowed to stay overnight.

The trail is constantly changing as the association gains and loses sites — weather destroys some and budgets cut others.

With the goal of having a safe pull-out every 5 to 8 miles, the group is always on the hunt for new locations.

Each summer, a Washington Water Trails Association crew tries to survey each site. Forging a relationship with state, county and city park rangers has been crucial.

Unlike many of the overcrowded hiking spots, in some stretches of the Cascadia Marine Trail it’s always been easy to find solitude.

When Joel Rogers traversed the entire trail, he didn’t encounter another human-powered watercraft using the route until he was more than halfway through his journey, according to his book published in 1998, Watertrail: The Hidden Path Through Puget Sound.

Though in the San Juans, on the night Rogers spent on Jones Island, his boat was one of 37 resting on the beach.

Dailer, the ranger at Meadowdale Beach Park, said about 10 groups pass through the campsite each year. Use is increasing. Starting this year, kids and leaders from a summer camp just a few miles away kayak into camp overnight each Wednesday.

“Being on the water you are humbled by Mother Nature,” Waite said. “The wind, the water, the currents, puts you in your place. It’s choose your own adventure. The possibilities are limitless.”

Lizz Giordano: 425-374-4165; egiordano@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @lizzgior.

•••

The shore is where the sacred water meets the sacred land.

It is tiny. It is fragile.

Walk gently upon our Mother Earth.

It is good like that.

—An excerpt from a Coast Salish blessing posted at the Meadowdale site

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.