EVERETT — A legal battle that Robert Preston started against a Snohomish County sheriff’s deputy in 2016, from behind bars at a state prison in Shelton, concluded this summer with a $150,000 payout.

Preston, now 52, alleged that deputy Ryan Boyer shocked him with a stun gun and beat him until he lost consciousness while he was in custody at an Everett park-and-ride in 2014.

The assault left Preston in a coma, with a collapsed left lung, two broken ribs, a fractured nose, a snapped tooth and a deep cut that partially severed his right ear from his skull, he said in his original lawsuit. He wrote the document by hand in prison and mailed it to U.S. District Court in Seattle in July 2016, later providing medical records to confirm most of those injuries.

Attorneys who were court-appointed to represent Preston the following year argued the county was negligent in hiring Boyer in light of past misdeeds. Before Boyer was a deputy, for example, he’d been arrested for fourth-degree assault in Arlington in 2002.

The settlement became final in June. It’s one of seven the county has agreed to pay in the past year in response to claims of misconduct and excessive force by sheriff’s personnel. Those payouts totaled about $600,000, records show, plus the cost of paying county attorneys who handled the cases.

Preston was under arrest in connection with a burglary reported earlier that day. According to Boyer, the suspect tried to run away. In police reports, Boyer acknowledged he used a stun gun on Preston, struck him in the head with the Taser twice and kicked him three or four times while trying to detain him.

The county defended Boyer’s use of force, saying in court papers that Preston was “volatile” and dangerous. The struggle occurred just after Boyer realized Preston was wanted on a $50,000 felony warrant, flagged in police records with a caution notice for officer safety.

Boyer is now a sergeant at the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office.

The county didn’t admit fault in any of the settlements. All but one of the seven payouts stemmed from incidents that predated the current sheriff’s administration.

The sheriff’s office declined to comment on any of the agreements.

One $35,000 settlement went to a county resident who alleged in a federal lawsuit that a deputy tackled him, shattering his clavicle, after falsely accusing him of jaywalking just south of Everett in 2018.

Another $21,000 settlement went to an 18 year old who claimed he was a victim of assault, racial discrimination and unlawful detention. He was arrested in July 2020 after taunting deputies with a doughnut at a pro-police rally in downtown Everett.

A $51,000 payout went to a Lynnwood man who claimed in a federal lawsuit that three deputies entered his home without a search warrant in June 2015 and shocked him with a stun gun moments later, exacerbating injuries he had sustained in a household accident.

Other settlements went to a man who was bitten by a police dog in 2017, a woman who repeatedly complained about a deputy harassing her in 2019 and a man whose car was searched without a warrant in 2019.

Jason Cummings, the chief civil deputy prosecutor for the county, said such payouts are a standard cost for police agencies because officers routinely have physical altercations, by the nature of their job.

“Law enforcement is a very high-risk business,” Cummings said.

The agreements were calculated decisions by the county’s attorneys meant to resolve the claims while protecting taxpayers from ultimately footing the bill for protracted legal battles, Cummings said.

In some cases, the settlements were made to avoid the costs of going to trial, Cummings said. The county’s lawyers also weighed the risks of putting some of the cases before a jury, given the current political climate, he said.

Last year, a nationwide movement against police brutality erupted from public outcry over the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other people of color at the hands of police across the country.

‘Serious questions’

Robert Preston is white, according to court records. His case underscores the hurdles that those injured by law enforcement must overcome to get financial restitution.

His lawsuit and the resulting settlement were first reported by The Seattle Times.

The plaintiff has spent much of his life behind bars, with a long record of burglary, vehicle theft, unlawful possession of weapons, eluding law enforcement and harassment.

His medical bills from the 2014 incident were roughly $70,000, according to court records.

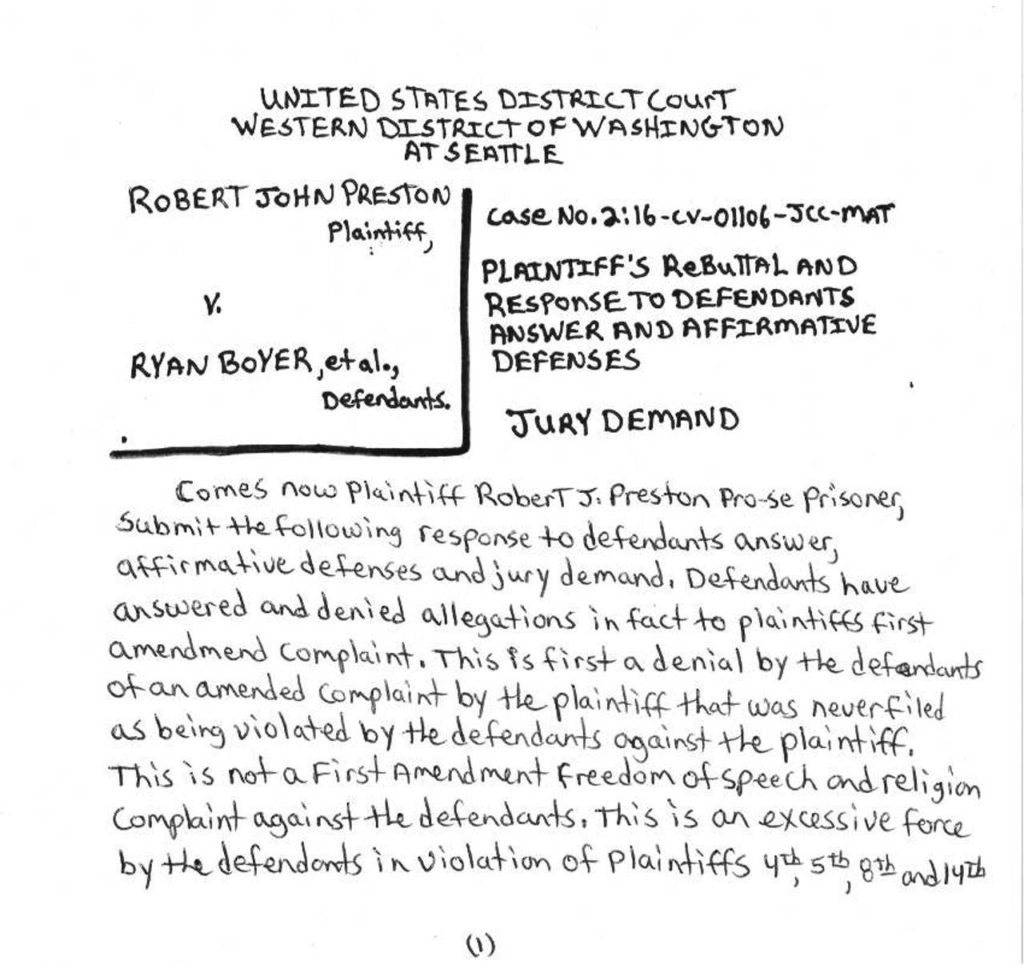

For nine months, Preston managed to push his civil case forward, hand-writing scores of pages of legal motions while serving prison time for unlawful possession of a firearm and other charges. A judge eventually agreed to appoint him an attorney in the civil case.

He had no access to a law library while incarcerated, and the system for submitting paperwork to the court was unreliable, he wrote in 2016. He was too poor to pay $32.50 needed to get procedural documents from the court clerk, he wrote in another filing.

Despite those obstacles, he gathered medical records, police reports and photographs of himself in the hospital, bloody-faced and intubated.

According to sheriff’s office records, Boyer’s encounter with Preston began as the deputy was investigating a report of a home burglary on July 30, 2014, in Edmonds. Preston lived in Edmonds at the time.

While searching the neighborhood, Boyer saw Preston with a bike that matched a description of one that was stolen, the deputy wrote in a report.

Preston initially identified himself as another person. Boyer detained him and later arrested him on suspicion of possession of stolen property and multiple stolen IDs, the report says. Preston insisted he didn’t steal the bike and that he borrowed it from someone else. So while driving to the county jail, Boyer stopped at the park-and-ride lot on 112th Street SE near I-5 to allow Preston to write a statement.

There, Boyer searched Preston’s wallet and realized his true identity.

The suspect was unpredictable, Boyer recalled in the report. Preston also wasn’t handcuffed and was 65 pounds heavier than Boyer, who was alone, the deputy said.

Boyer ordered Preston to get on his knees. Instead the suspect tried to flee, so Boyer shocked him with a stun gun. Preston fell to the ground. Boyer got on his back in effort to control him, the deputy reported. When Preston continued to resist, Boyer hit him in the head with the stun gun, kicked him and shocked him again.

Other deputies arrived. Preston was taken to Providence Regional Medical Center Everett to be cleared for booking into the jail.

Preston said in the lawsuit he woke up in the intensive care unit a day later. Medical records show he was at the hospital for a week.

He arrived at Providence covered in blood, with cuts on his ear, forehead, lips and scalp, according to an examination report. The severity of his coma suggested a serious head injury. Doctors suspected he might have had a seizure when he was shocked.

Preston was also diagnosed with a broken nasal bone, skull fractures and a collapsed left lung, the medical records show.

Court records show he later pleaded guilty to identity theft for using another man’s ID to say he was someone else.

In 2017, U.S. District Court Magistrate Judge Mary Alice Theiler agreed to appoint an attorney for Preston after the court twice denied his previous requests for counsel.

“Although defendant disputes plaintiff’s account of events, if the evidence currently in the record is viewed in plaintiff’s favor, there are at least serious questions regarding the constitutionality of defendant’s actions,” Theiler wrote in an order.

The legal issues at hand were too complex for Preston to represent himself, the judge concluded.

Deputy’s hiring questioned

High-profile law firm Perkins Coie, of Seattle, then took him on as a client, bolstering his claim with arguments about Boyer’s background. The firm filed an amended lawsuit on Preston’s behalf, naming Snohomish County as a defendant.

The attorneys alleged in another court filing that Boyer’s supervisor did not review his use of force report after the incident, as required by sheriff’s office policy. Nor was the report forwarded to a bureau chief, as is the agency’s policy if a suspect is injured.

Perkins Coie also recruited Scott DeFoe, a former Los Angeles police officer and expert witness in police procedure, to review the case.

DeFoe wrote in a 2017 report that Boyer used “excessive and unreasonable force.” He opined in another report that the county should not have hired Boyer, based on what they knew about his background.

Boyer was hired by the sheriff’s office in late 2011, after the sheriff took over the Snohomish Police Department under a new contract, according to legal filings.

Court records with information about his personal history are heavily redacted, as a judge ruled it was necessary to “to avoid disclosure of highly personal information.”

Unredacted portions of the records say Boyer was arrested in 2002 for fourth-degree assault, a misdemeanor, after one of his friends started a fight outside an Arlington bar. The charges were dismissed when Boyer completed 12 months of probation.

During the hiring process, a deputy who investigated Boyer’s background determined Boyer had no criminal history since 2002, according to court records.

That deputy recommended Boyer should be hired, noting positive comments others had made about him and concluding that Boyer had apparently learned from his mistakes.

The county disputed the claim that the sheriff’s office was negligent in its decision to hire Boyer and keep him on the force.

None of the infractions from his teens and early 20s were serious enough to be considered “automatic disqualifiers” for employment at the agency, said Joe Genster, an attorney for the county who worked on the case. Other law enforcement agencies, too, would likely have been willing to hire him, in spite of his past, Genster said in an interview with The Daily Herald.

Genster pointed to a 1991 news report by the Los Angeles Times that said DeFoe was once arrested after a fight outside a cafe.

Boyer has had no disciplinary history with the sheriff’s office over the past decade of employment, Genster said.

In January 2020, Judge John C. Coughenour denied a motion the county filed for summary judgment, saying “a genuine issue of material fact exists on the issue of whether the County was negligent in retaining Sergeant Boyer.”

The $150,000 settlement was reached in late May 2021, court records show.

Preston’s attorneys originally sought more than $1 million, Genster said.

Other recent settlements

• $21,000 in response to the claim of Benjamin Hansen, settled in November 2020.

Hansen submitted a damage claim to the county in July 2020 alleging he was assaulted by a law enforcement officer and subject to racial discrimination during a pro-police rally in downtown Everett that month, and then unlawfully detained for a day.

Hansen, an 18-year-old counter-protester at the event, teased a group of law enforcement officers by dangling a doughnut tied to a stick with a string. One sheriff’s lieutenant, in plain clothes, became angry. Videos of the encounter were widely shared on social media.

A marshal then shoved Hansen, one video recorded by a bystander shows. Hansen asked the young woman recording the video if she caught it on camera, and asked the deputies for their names and badge numbers. They didn’t respond. Instead, the marshal arrested Hansen.

The marshal wrote in an arrest report that Hansen pushed the stick and doughnut toward the face of the lieutenant’s face, who couldn’t back up any further to avoid getting jabbed because he was standing in front of a retaining wall.

Hansen, of Duvall, was booked into the Snohomish County Jail for investigation of fourth-degree assault and released the next day after posting bail of $1,000.

Snohomish County Prosecutor Adam Cornell reviewed video of the incident and declined to charge Hansen.

Caution: This video contains potentially offensive language.

• $35,000 in the case of Snohomish County resident Kevin Stagner, settled in November 2020.

Stagner, 35, alleged a deputy tackled him after falsely accusing him of jaywalking, according to a lawsuit he filed in U.S. District Court in Seattle in October 2020.

Stagner, a county resident, claimed the deputy approached him after he crossed Center Road, south of Everett city limits, in August 2018. Stagner reportedly asked if he was being detained, and the deputy said he was not. Then, the lawsuit says, the deputy slammed him into the ground and pinned him to the pavement, injuring his shoulder.

Stagner was later diagnosed with a broken collarbone that required surgery, according to the lawsuit.

He also spent nearly two months in jail awaiting trial on charges of resisting arrest, the lawsuit says. After one trial ended with a hung jury, a second jury acquitted him in 2018.

• $51,000 in the case of Virgil Armstrong, of Lynnwood, settled in February.

Armstrong was seriously injured when he bumped into and shattered a large glass fish tank during a sleepwalking episode in his apartment in 2015, according to his complaint in the case.

Armstrong cried for help. Three deputies arrived with their weapons drawn and ordered him facedown on the floor, which was covered in broken glass, says Armstrong’s lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court in Seattle in 2018.

Armstrong refused to get down, afraid to hurt himself further. The deputies shocked him with stun guns, according to Armstrong’s complaint. As he convulsed on the floor, his cuts and wounds worsened. His injuries included a lacerated Achilles tendon, doctors later told him.

The deputies disputed parts of Armstrong’s account. He was covered in blood and acting erratically when they entered the apartment in response to his screams for help, they said in court records.

There was no glass on the floor of the apartment, the county’s attorneys argued.

Photographs later taken of the scene showed almost everything inside was overturned or upended, and the carpets and furniture were covered in blood.

The county said deputies fired their stun guns when Armstrong refused to get on his belly, and that he began walking toward them. They suspected he was in the midst of a mental health episode and potentially dangerous.

Once Armstrong was subdued, he was taken to a hospital.

Attorneys for Preston and Armstrong did not return phone calls requesting comment on their cases. Everett civil rights lawyer Braden Pence, who represented Stagner and Hansen, said he had no comment on the settlements.

Rachel Riley: 425-339-3465; rriley@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @rachel_m_riley.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.