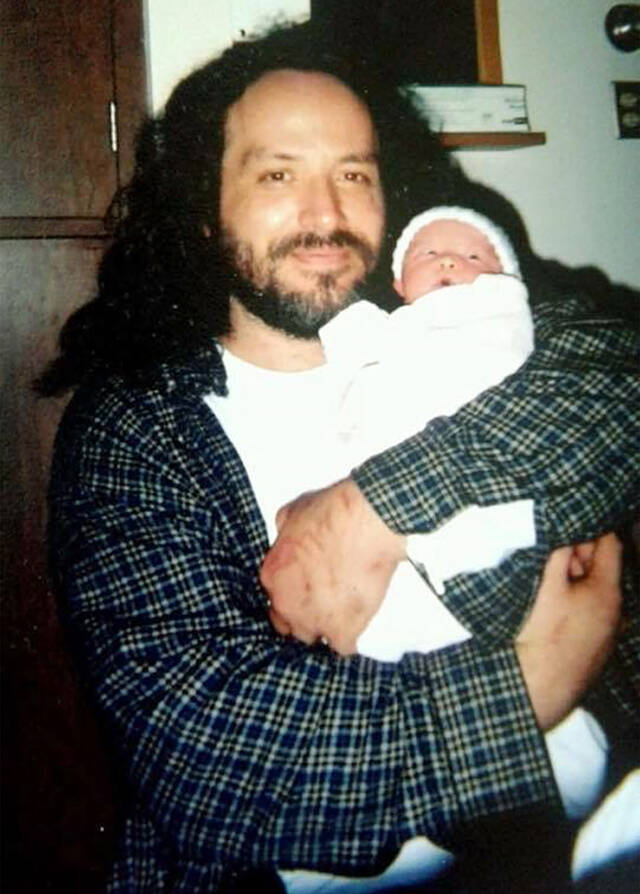

EVERETT — Snohomish County has agreed to pay $1.75 million to settle a lawsuit brought by the family of a tribal member who died in a confrontation with law enforcement officers on the Tulalip Indian Reservation in 2015.

At a Monday night meeting, the County Council unanimously approved the payout to the estate of Cecil Lacy Jr., who was 50.

His family’s lawsuit, filed in King County Superior Court in 2016, alleged Lacy died of asphyxiation while Snohomish County sheriff’s deputy Tyler Pendergrass put weight on his back and two other Tulalip police officers helped pin him to the ground.

Snohomish County’s chief medical examiner previously attributed Lacy’s death to a heart attack due to methamphetamine in his system and several other factors, including the struggle with police. Lacy also had an enlarged heart, obesity, hypertension and mental health issues, the medical examiner concluded.

In 2016, then-Snohomish County Prosecutor Mark Roe said the officers’ actions that night were legally justified. Roe, who has since retired, determined that none of them would face criminal charges.

The county admitted no fault in the settlement, which became final on Tuesday. Jason Cummings, the county’s chief civil deputy prosecutor, said the agreement “speaks for itself.”

The family is still seeking answers about Lacy’s death, his widow Sara Lacy told The Daily Herald on Tuesday.

“But for now, we’re very happy about the settlement, and that we’ve got that for our kids,” said Sara Lacy, who had three adult children with Cecil Lacy Jr. “It’s been a long fight, and it’s time for us to start the healing process.”

In a letter to state officials last year, the family’s attorney accused the detective who led Lacy’s death investigation of changing Pendergrass’ account of the incident and manipulating the medical examiner’s findings, in order to protect the deputy from the consequences of his actions.

The Lacy family and the Tulalip Tribes called on state leaders to launch an independent review of the death, which had been investigated the Snohomish County Multiple Agency Response Team. Also known as SMART, the cadre of detectives and other specialists from around the county investigates police use of force.

Gov. Jay Inslee will refer Lacy’s death investigation to a new state office, created this year by police reform legislation, that’s tasked with conducting unbiased investigations of possible cases of police brutality. The Office of Independent Investigations will also review other deaths with similar circumstances, Inslee’s press secretary Mike Faulk said in an email.

Given that several other in-custody deaths in Washington have drawn similar calls for independent investigations, Faulk said, Inslee decided “the most appropriate and fair thing to do was to refer all of these cases” to the new office once it’s up and running.

“Right now there is no existing agency that has the capacity to conduct multiple investigations of this nature,” Faulk wrote.

According to a summary of the SMART investigation, Lacy was on a nightly walk when Pendergrass and the other two officers found him near the 6400 block of Marine View Drive around 10 p.m. Sept. 18, 2015.

Law enforcement had received a call about a man waving his arms in the street.

The officers suspected Lacy was drunk or high because he was agitated and sweaty, according to the SMART investigation. Lacy told them he had previously been institutionalized for mental health issues.

The officers offered Lacy a ride home, but he tried to escape from a patrol car, says the SMART case summary. He got upset when officers told him he would need to be handcuffed during the ride home for their safety. Pendergrass used a Taser on Lacy while trying to control him, but the device was ineffective, according to the case summary. The deputy told SMART investigators that he used the weight of his upper body to prevent Lacy from standing up.

After Lacy’s body went limp, the officers tried to revive him without success.

In the years after Lacy’s death, police brutality became a subject of increased national public outcry. His widow joined the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, which has successfully lobbied for the passage of laws meant to prevent tragic deaths like her late husband’s.

“It felt really good to be productive, even while we waited for our own trial,” Sara Lacy said.

The family’s attorney, Seattle-based indigenous rights attorney Gabe Galanda, has said Lacy succumbed in the same position as George Floyd, who died in May 2020 as a Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck.

Lacy’s last words, too, were “I can’t breathe,” according to the family’s lawsuit.

“That entire set of reforms is a step in the right direction,” Galanda said, of Washington’s newest police accountability laws. “But the fact remains that, in situations like this one, there are concerted efforts by local officials and actors to conceal the truth associated with law enforcement’s mistakes or wrongs — such that we never know exactly what happened in order to prevent it from happening again.”

While litigating the case, the family turned up evidence that Pendergrass was placed on administrative leave just months after Lacy’s death amid allegations that he threatened domestic violence and misused a stun gun.

Lake Stevens police investigated the domestic violence allegations and referred the matter to their city prosecuting attorney, who declined to file charges, according to court filings in the civil lawsuit.

A sheriff’s investigator determined Pendergrass did violate two department policies, however, when he kept a stun gun that he confiscated from a Tulalip tribal member and used it while off duty without explanation, court records show. Pendergrass was issued a written reprimand in April 2016 for those violations.

The Lacy family initially sought $4.5 million in damages from the county, according to a claim submitted in April 2016. Their lawsuit accused the sheriff ’s office of negligence and excessive force.

A Superior Court judge dismissed the lawsuit in 2018 before it reached a jury, concluding there wasn’t sufficient evidence to support the claim of excessive force.

Then, in the fall of 2020, a state Court of Appeals ruled that that family’s attorneys could argue the case at trial.

According to the Court of Appeals, the trial judge was correct in dropping the lawsuit’s negligence claim but erred in dismissing the allegation of battery.

The Court of Appeals wrote: “We cannot conclude, as a matter of law, that (the deputy) acted reasonably when he applied and maintained pressure on the back of a handcuffed, unarmed, mentally ill and agitated human being who was in a prone position, exclaiming that he could not breathe. That decision should have been left to the jury.”

The case was previously set to go to trial this week, but the parties notified Superior Court that a settlement had been reached on Nov. 23, court records show.

Rachel Riley: 425-339-3465; rriley@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @rachel_m_riley.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.