EVERETT — Forty years ago the search for her name began with the discovery of her death.

Berry pickers came across the young woman’s body Aug. 14, 1977, in a wooded area in south Everett.

She was wearing a pastel, striped tank top, cut-off jean shorts and size seven blue Mr. Sneekers tennis shoes. A Timex watch with a yellow face was on her left wrist, the leather band fastened at the second-to-last notch. In the pockets of her shorts were 17 cents, a partial pack of Marlboros and an empty plastic bag.

She was brunette, tan and tall, maybe 5-feet, 10-inches. A forensic anthropologist later estimated she was between 15 and 21, likely 16 to 19.

The medical examiner dug seven bullets out of her head. Her killer would later tell detectives he wrapped a bungee cord around her neck when she turned down his advances. She urinated in the front seat of his car as he choked her. He dragged her out of the 1963 Chevy Nova and emptied his rifle into her.

David Marvin Roth, 20, left the young woman there among the blackberry brambles. He told police she was a hitchhiker he picked up on Aug. 9, 1977, on the Bothell-Everett Highway on the east side of Silver Lake. Roth claimed he never got her name, said she didn’t have a purse.

“You pick up a stranger, a hitchhiker, she’s not going to tell you her name. You’re not trying to get personal. She didn’t ask me my name,” Roth told The Daily Herald in 2008, three years after getting out of prison for the murder.

If Roth knew her name, the secret went with him to the grave. Roth died of cancer Aug. 9, 2015 — 38 years to the day he killed the young woman.

She has been Jane Doe, case #77-17073, for decades. To Snohomish County sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf, she’s “Precious Jane Doe.”

The veteran homicide detective and Jane Jorgensen, an investigator with the county medical examiner’s office, have intensified efforts to find the young woman’s name. The work has been ongoing as technology improved and the Internet widened their search beyond law enforcement resources.

The latest approach to finding Jane Doe’s identity could depend on the curiosity of others searching for distant relatives and clues to family lineage.

With advances in DNA profiling, a person with $100 to spare can send in a saliva sample to a private company to map their genetic make-up and to compare to others. Genealogy buffs often share their genetic blueprint online in an effort to trace their roots and flesh out the family tree beyond the memories of relatives.

Jorgensen recently sent Jane Doe’s bones and teeth to a private lab in the hopes that a viable DNA sample can be extracted to sequence the young woman’s entire genome, a complete genetic map that may hold the key to her identity.

The plan would be to share that information with Colleen Fitzpatrick, a physicist turned forensic genealogist consultant, who has helped investigators elsewhere identify the unnamed dead and suspected killers. Scharf consulted with her years ago while trying to track down the surname of a possible suspect in a cold case. They exchanged messages recently, and she said she might be able to help with Jane Doe. Fitzpatrick, founder of Identifinders International, can tap into other genetic profiles shared online and make comparisons.

Investigators hope a cyber search will lead to one of Jane Doe’s relatives.

She was likely born between 1956 and 1962. That means her mother, if living, could be in her 70s, possibly older.

“It feels like we’re running out of time,” Jorgensen said.

Scharf picked up the case in 2008 after taking a call from the Doe Network, a Web-based group that cross-references missing persons cases against unclaimed bodies.

Experts estimate about 110,000 people are considered missing in the U.S. The unidentified remains of about 60,000 people are buried in unmarked graves or stored in boxes in medical examiner offices across the country. Physical descriptions for only about 15 percent of those remains have been entered into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center.

Jane Doe’s DNA was not on file in the national Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, a repository for the genetic profiles of convicted felons. The index also houses profiles of the relatives of missing persons, if they’ve submitted a buccal swab for testing. That hasn’t been a common practice until recent years.

When Jane Doe was killed, investigators didn’t know about forensic DNA. Unidentified remains were buried, often compromising any chances of recovering DNA later.

Sheriff’s detectives consulted with experts, who agreed the young woman’s remains should be exhumed. Scientists might be able to extract her DNA from long bones to be compared against those in the national database.

About 29 years after she was buried, Jane Doe’s remains were unearthed from a plot at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Everett.

Anthropologist Dr. Kathy Taylor examined the skeleton, concluding that the victim was younger than detectives first believed. In the early days, they estimated she was in her 20s or 30s.

Her bones in 2008 were sent to the Center for Human Identification at the University of North Texas. Forensic scientists there analyze genetic samples from unidentified remains. They also collect samples submitted by the relatives of missing persons.

Scientists were able to extract a sample from Jane Doe but it didn’t match any profile in CODIS. The testing being done now requires a new sample.

Scharf learned along the way how easy it could be for Jane Doe to slip through the cracks. Families may not know to submit a DNA sample for comparison against unidentified remains. If she was reported as a juvenile runaway, once she turned 18 the report may have been purged from law enforcement databases.

Scharf requested officials at the FBI’s National Crime Information Center run an offline search capturing data of all the missing women matching Jane Doe’s physical traits, and whose cases were removed from the database between 1975 and 1980.

The detective got back a list of 39,447 missing women. The list doesn’t tell him if any were found or why their files were removed.

Scharf and his former partner David Heitzman turned to Roth for help. Did he know her name? Did she tell him where she was from? Was a new sketch of the young woman accurate?

Roth said he was surprised investigators still didn’t know her identity.

“I felt stupid I’m alive and she was dead,” Roth said in 2008. “There’s no telling what she would have been.”

Roth was arrested in Gold Bar a few days after the killing. Someone complained about a man waving a gun around in a park. He was stopped on U.S. 2 and officers spotted marijuana and roach clips in his ashtray. They also noticed a .22-caliber rifle in the Nova. The car was impounded and Roth went to jail for a night or two.

He didn’t keep his secret for long. A week after his arrest a man contacted Seattle police, reporting that his buddy admitted to killing a hitchhiker he picked up in Everett.

The medical examiner had the young woman’s body by then. Police searched Roth’s impounded car. Inside, they found bungee cords, peacock feathers and shell casings.

Ballistic tests eventually matched the slugs recovered from the victim with Roth’s rifle. Detectives went looking for their suspect. He was arrested in Port Orchard in early 1979 and on the ferry ride back to Everett he confessed.

He picked her up, drove to the Midland Grocery, where he bought them beer. They parked near the 11300 block of Fourth Avenue W. He handed her a peacock feather and asked for sex. He became enraged when she refused him.

A jury convicted Roth of first-degree murder, and he was sentenced to life in prison. He spent 26 years behind bars before convincing the parole board he was fit to be released. He moved to Everett with his wife. That’s where Scharf found him in 2008.

The Daily Herald interviewed Roth that fall. He said he wanted to help find the victim’s family.

“I see the detectives going out of their way to find her identity. When these guys asked, I told them I’d do whatever I could. I can no longer help her, but I can help those who are looking for her. Some things we have to do,” he said.

Scharf has tracked down leads that trickled in over the years. After the newspaper’s story ran, a man called, recounting the young woman who’d been hanging around his Silver Lake neighbor’s house. He thought she was from California. She had dropped out of sight.

Scharf found a girl missing out of the Los Angeles area who was removed from the system after she turned 18. It was a good lead. “She could be the one,” he remembered thinking. He found the woman living in Montana. She told him she and a girlfriend had run away but returned home about a week later. Files were never updated to reflect her return.

The detective has ruled out missing people from as far away as Australia. He has talked to plenty of desperate families who wonder if Jane Doe is their missing daughter or sister.

A woman reached out to Scharf last year, asking if her missing sister might be “Precious Jane Doe.” The woman wondered if the authorities had the right dental records for her missing sister. Scharf helped answer that question.

“I always get excited if a tip sounds promising, but I’ve learned to be very patient and not to let disappointments bother me very long,” Scharf said.

Investigators have ruled out 60 missing women through their research.

They aren’t done looking.

Jorgensen learned that not all police agencies upload fingerprints to a national database. She’s made contact in all 50 states and plans to send Jane Doe’s prints to those agencies for comparison.

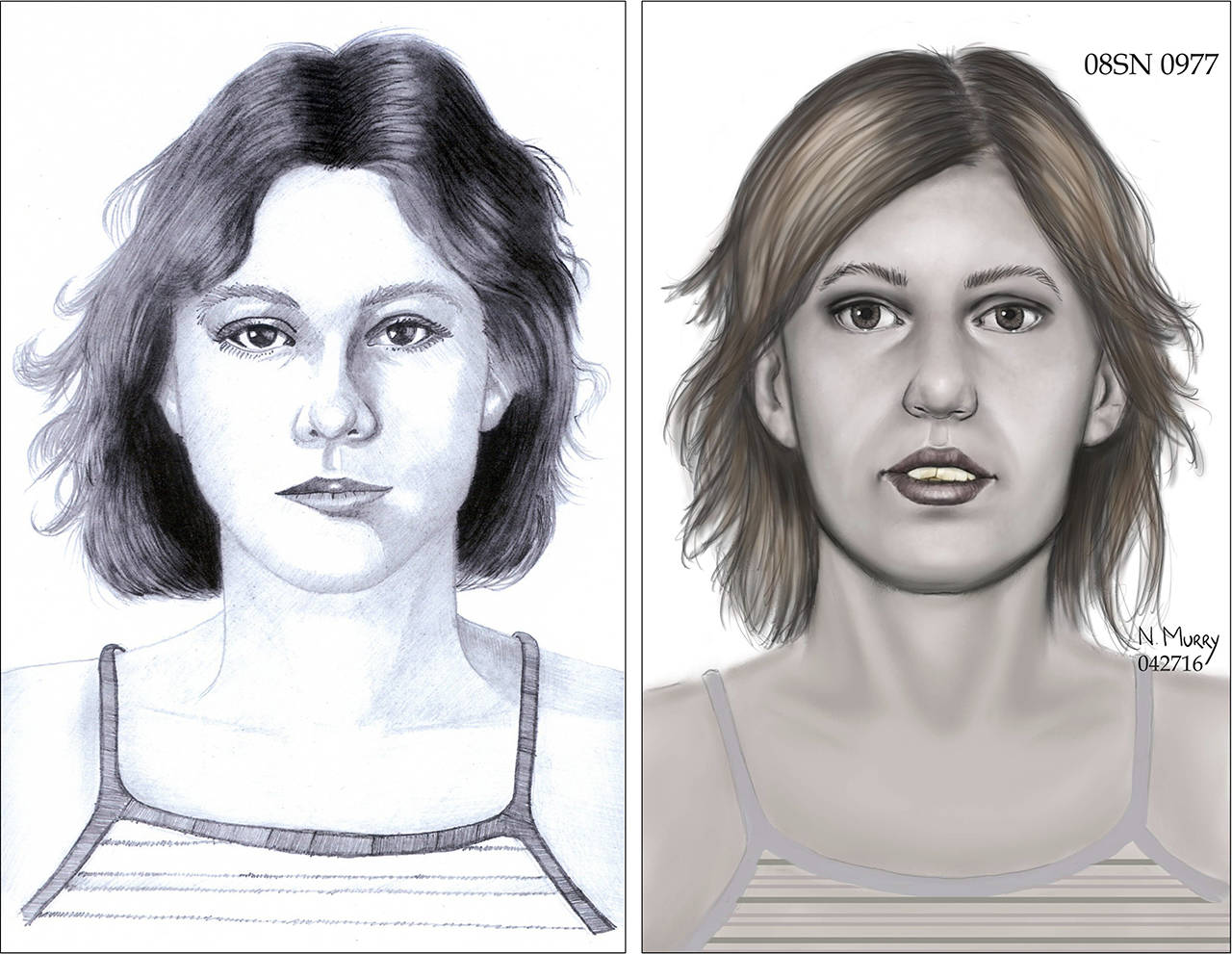

Last year her office hired a forensic artist to sketch Jane Doe and several other unidentified people based on skull reconstruction. That sketch of Jane Doe bears a striking resemblance to the one done in 2008.

The artist drew the young woman’s mouth slightly open, revealing her upper two front teeth. A forensic dentist determined those teeth had been cracked or broken and had undergone extensive restorations.

“We wanted to get a second opinion,” Jorgensen said, of getting the new sketch. Maybe the computer program caught her likeness in a way that will spark someone’s memory.

It is hard to believe no one has been looking for her all these years, Jorgensen said.

Maybe it’s finally their time to find her.

Diana Hefley: 425-339-3463; hefley@heraldnet.com.

If you have information

Jane Doe’s body was found Aug. 14, 1977, in south Everett. She was about 5 feet, 10 inches tall, 155 pounds with brown hair. She likely was born between 1956 and 1962. Anyone with information is asked to call 425-438-6200 or send an email to Contact.MedicalExaminer.Investigation@co.snohomish.wa.us.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.