In the studio of her Everett home, Susan Ringstad Emery is surrounded by artwork, along with the brushes, paints and other tools she uses. Much of her inspiration, though, is more than 2,200 miles away.

A visitor’s eyes are drawn to an acrylic painting of a polar bear, unfinished and with a colorful abstract background.

Emery’s art reflects her heritage. Her ancestry is Inupiaq and Scandinavian. She is an enrolled tribal member of the Native Village of Shishmaref in Alaska. Born in Seattle’s Ballard area, her childhood was split between Western Washington and Anchorage. Norway was the homeland of the Ringstad side of her family.

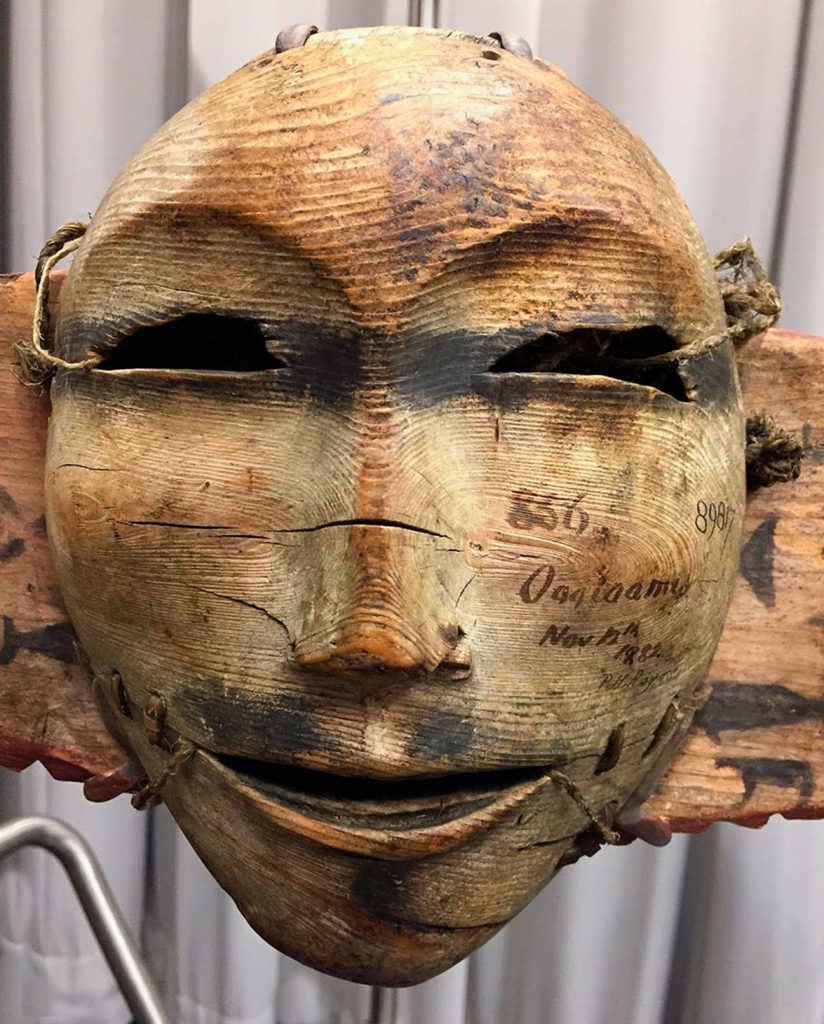

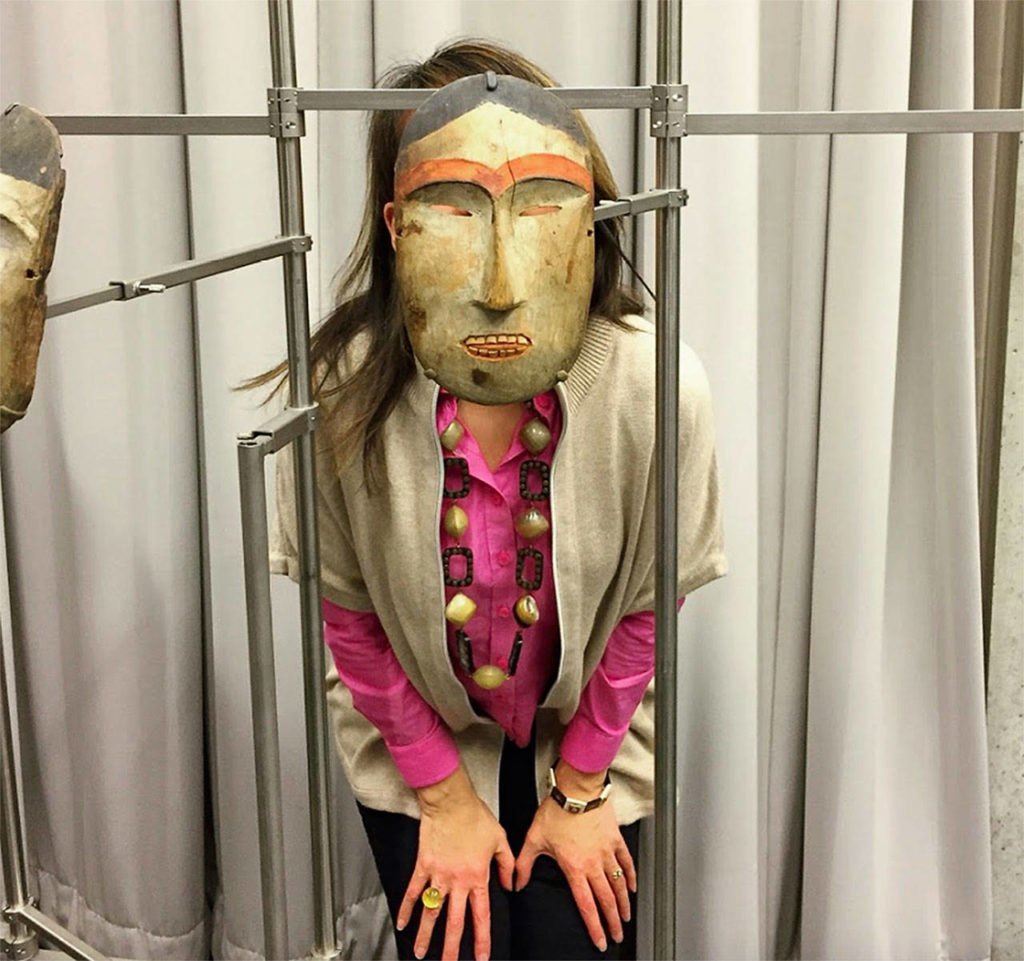

Last month, she spent several days at the Anchorage Museum, where she viewed and spent hours with artifacts — many related to her ancestors’ culture. Emery, 50, was chosen to participate in the Polar Lab Collective, a program for Alaska Native artists. It’s a collaboration between the Anchorage Museum and the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center.

The Anchorage Museum has “a huge collection” of items on loan from the Smithsonian Institution, “beautifully displayed,” Emery said. Her experience at the museum, Nov. 14-18, strengthened her bond to her heritage and inspired the art she’s now creating.

“I was looking for any items made by our people for our people,” Emery said Wednesday. “I felt some of these artifacts were alive. They have energy.”

An accomplished artist, Emery’s works have been shown in the New York Grand Central Terminal, the Alaska Native Heritage Center and Seattle’s Nordic Museum. In her downstairs studio, she shared stories of the artifacts and showed what she has made since seeing them.

A 7.0 magnitude earthquake shook the Anchorage area Friday — by chance just days after Emery described the movable metal racks the museum uses to tether precious items from the Smithsonian. The practice is meant to safeguard artifacts from quake damage.

A call to Monica Shah, the Anchorage Museum’s director of collections and chief conservator who worked with Emery, understandably went unanswered Friday. That was likely due to Friday’s two earthquakes, which news reports said ruined roads, cracked buildings and broke windows.

“Monica was with me, she was there with her computer,” Emery said. Artists, who must be Alaska Native, apply for the Polar Lab and participate one at a time.

A mother of four whose husband John Emery is a software engineer with the Fluke Corporation, she studied art at Everett Community College while raising their family.

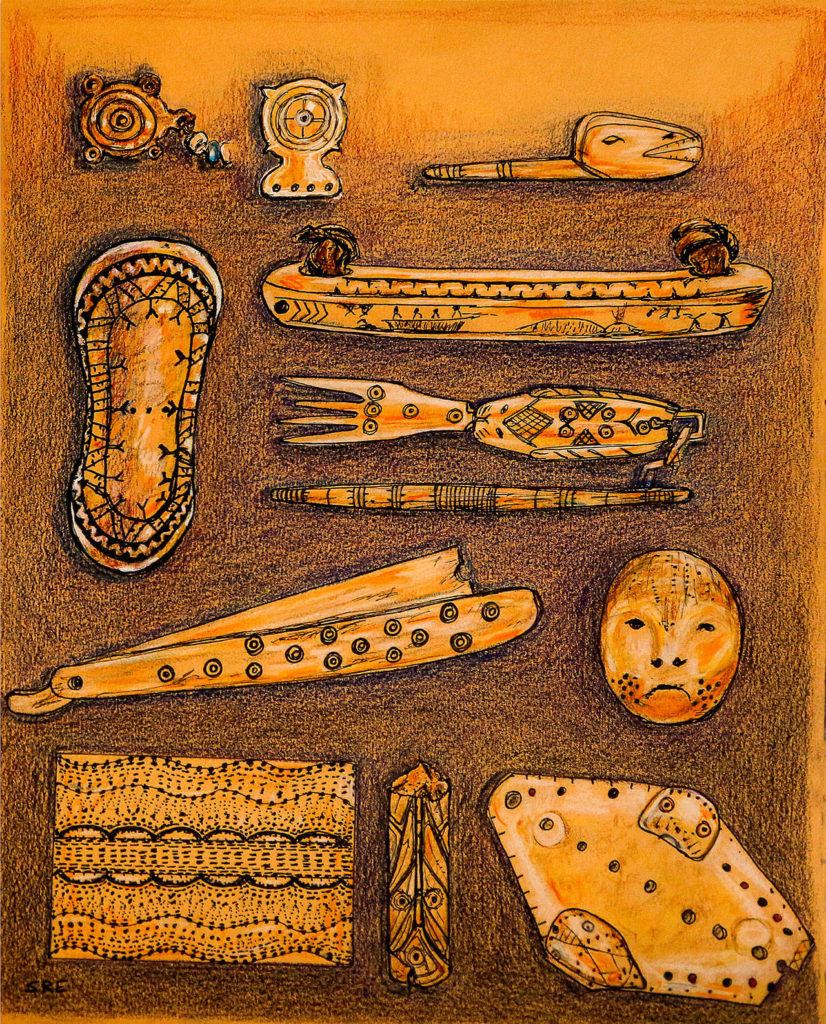

Expanding on her sense that the artifacts have life in them, Emery said “drawing them has really helped me see.”

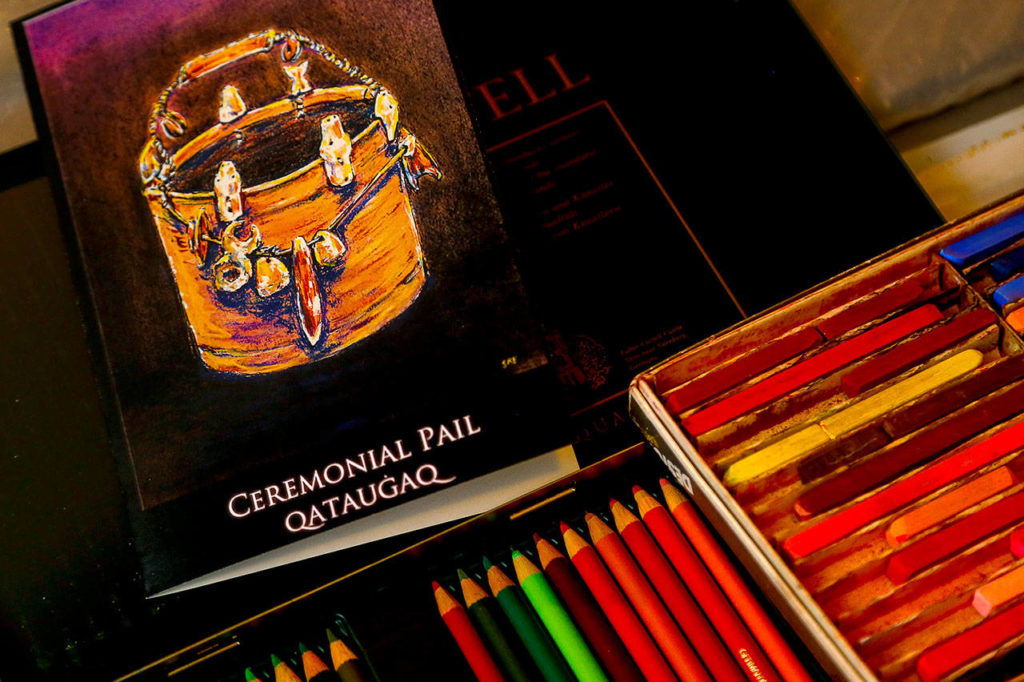

She showed her drawing of a ceremonial pail from the Smithsonian — a beautiful object of steam-bent wood, adorned with polar bear teeth carved into bear heads and whale tails. After a whale hunt, a captain’s wife would use the pail to pour fresh water on the animal, showing respect, Emery said. “She’d sing her welcome to its spirit.”

Emery said she’s descended from hunters, fishermen, ship builders and a shaman. She found one surprise at the Anchorage Museum.

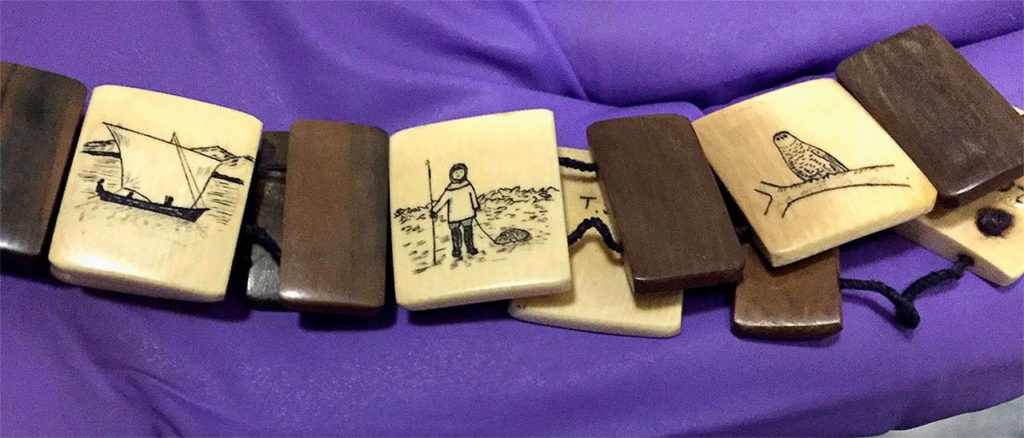

“We were looking in some of the archives, which drawers might have artifacts from my ancestors’ region, the Bering Straits,” she said. Those ancestors lived in the Wales area, near the Arctic Circle. “I saw this bracelet,” she said, pointing out a photo of the scrimshaw piece.

The bracelet’s fossilized ivory squares, etched and inked with images of a boat, an owl and a man, also show initials, T.S.

“I think my grandfather made this. It was the right region and time,” Emery said. Her grandfather was Teddy Sockpick. She shared pictures of the bracelet with cousins on social media. She learned that one cousin’s mother had said Sockpick used owls in his art, and later signed his works T. Sockpick.

Census records from 1940 show Teddy Sockpick, born about 1908, as living in Shishmaref, with the address “North Side of Only Street.”

“My cousins were super excited,” she said. “Did that artifact want to be identified? Was it fate?”

Along with drawings of the pail, mukluks and ceremonial walrus and raven masks, Emery has made pictures of tools and other carved artifacts.

One drawing in her studio is the face of an elderly woman. It’s a portrait of Emery’s great-grandmother, Annie Koonuk, known in the family as “Auka” or grandmother. “Herbert Nayokpuk was one of her sons,” Emery said. Nayokpuk, who died in 2006, was a famed Iditarod race musher known as the “Shishmaref Cannonball.”

“None of our ancestors spoke much English,” she said. “And my siblings and I weren’t taught our native language.”

Emery has tried learning Inupiaq, a dialect of Inuit languages. With not much success at that, she’s studying Norwegian instead. She has been invited to show her art in Norway this summer, but with a grandchild on the way she doesn’t plan to make the trip.

Grateful to have been chosen for the Polar Lab Collective, she said those who get that opportunity are inspired to carry on ancient traditions, creating a ripple effect through their art. Things she saw in the museum have become a part of her.

The pieces “were a lot more spiritual than I expected,” Emery said. “It’s like the artifacts are whispering, but it’s not audible.”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.