By The Herald Editorial Board

You can’t argue with success, but maybe state lawmakers ought to allow for some checks and balances.

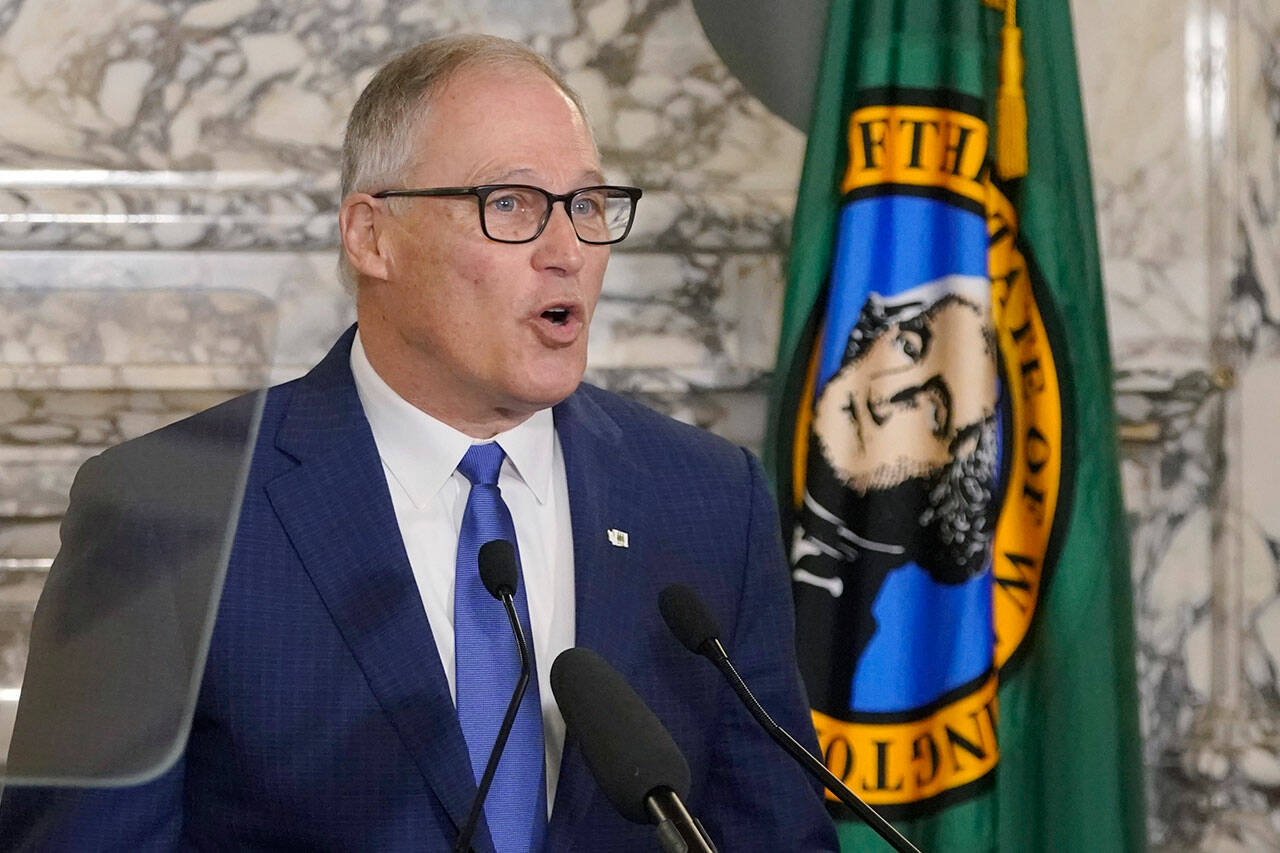

Two pieces of legislation before state lawmakers — one from each chamber — seek to allow for reconsideration of the governor’s authority to declare a state of emergency and issue orders and restrictions, such as Gov. Jay Inslee’s emergency orders, which began two years ago, related to the covid-19 pandemic.

Because Washington state was among the first in the country to experience an outbreak of covid-19, Inslee was among the first governors to declare an emergency and issue orders that sought to limit spread of the disease through initial stay-home mandates, orders that closed or severely restricted businesses, set limits for the size of public and private gatherings, moved public schools to remote learning, required vaccinations for health care workers and state employees and required masks to be worn in public.

Those orders were not without personal and public sacrifice and pain, but they also — as intended — have been successful in limiting the covid case rates and deaths in Washington state over the last two years. Washington state continues to have one of the lowest rates for cases and deaths in the nation, ranking seventh lowest for cases per 100,000 residents (17,000, compared to Rhode Island’s high of 32,228); and sixth lowest for deaths per 100,000 residents (141, far less than half that of Mississippi at 364 and Arizona at 360).

Regardless of statistics, some among both parties in the Legislature are asking if those decisions should be left to the governor alone.

“Why is that important?” asked state Rep. Chris Corry, R-Yakima, during a hearing for the legislation he sponsored, House Bill 1772, which seeks to increase legislative oversight of emergency orders. “Article 1, Section 1 of our (state) constitution states that all political power is inherent with the governed. In order for us to honor that and honor our oaths as representatives we should be party and part of those discussions.”

Corry’s legislation would limit a governor’s state of emergency to 60 days and orders prohibiting certain actions to 30 days unless extended by the Legislature. HB 1772 would also reduce the penalty for wilful violation of emergency orders from a gross misdemeanor to a civil infraction.

Senate Bill 5909, sponsored by state Sen. Emily Randall, D-Bremerton, would — after 90 days of an order being issued — authorize the majority and minority leaders of the Senate and the speaker and minority leader in the House to terminate a state of emergency or its restrictions, if all four are in agreement and the Legislature is not in session.

The Legislature currently does have the power to rescind a governor’s orders, but it requires a two-thirds majority in each chamber, a high-bar for reconsideration.

“Our neighbors recognize that there’s a gap in the checks and balances of our system of government,” Randall said, introducing her legislation during a committee hearing, “that there’s a place where we don’t have an equal balance of power.”

Supporters of the legislation have pointed to a 50-state scorecard on emergency orders produced by the Maine Policy Institute, a free-market think tank in Portland, Maine, that ranked Washington near the bottom because the governor has sole authority to declare and end states of emergency.

But that scorecard may not be as helpful in arguing the case against a governor’s authority as claimed. Among the worst offenders in the institute’s eyes — Washington, Vermont and Hawaii — those states are among leaders for lowest per capita death rates from covid, while Kansas and South Carolina — ranked highest on the scorecard because their governors must seek legislative approval after 15 days — ranked 20th and 33rd respectively, 258 deaths per 100,000 for Kansas and 297 deaths per 100,000 for South Carolina.

Maine, by the way, which allows its legislature to terminate a governor’s orders by a simple majority vote, fell in the middle of the pack on the institute’s scorecard, but ranks just above Washington state for its covid per capita death rate, 129 for every 100,000 residents.

Case rates and lives saved are apt measures with which to measure the effectiveness of Gov. Inlsee’s emergency orders on covid. And arguments that the length of those orders — more than 700 days now — point to the governor’s overreach, fail to fully acknowledge the resilience of a pandemic that has during the last two years ebbed at times only to come surging back. We are only now seeing the peak and hopefully the decline of the omicron variant’s surge, whose case rates have far eclipsed previous surges and overwhelmed our hospitals and medical workers. The success of Inslee’s orders has depended on his ability to respond quickly as the pandemic changed, allowing restrictions to be relaxed when appropriate and tightened when necessary.

At the same time, that success has come at significant cost in terms of children’s lost time in classrooms, in unemployment, in businesses closed and in family gatherings canceled. Those costs to Washington residents should be recognized with a clearer path to review of a governor’s emergency orders than now exists. And such a review could allow for greater public confidence in those orders.

SB 5909 appears to strike the best balance between the appropriate authority of a governor and the ability of legislative representatives to keep that authority in check.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.