Their names are still with us.

They are sprinkled here and there across Snohomish County, on buildings where former soldiers meet and on street signs if you look in the right places. They’re etched in stone and appear on plaques at city halls and high schools.

They are in books, obituaries and blurry microfilmed stories from local newspapers.

Some can be found on weather-worn gravestones.

It’s the same story in counties across the country and communities around the globe.

More than 9 million soldiers from many nations died during World War I. Another 20 million were wounded.

The U.S. entered the war in April 1917, three years after it began. German U-boats were sinking American merchant ships in the North Atlantic. The time had come to abandon the neutral corner and take a stand. “The world must be made safe for democracy,” President Woodrow Wilson declared, and it would be “the war to end war.” Soon thereafter, young men were enlisting and local draft boards toiled toward their quotas.

The war ended Nov. 11, 1918. Six years later, the U.S. War Department reported its final tally: 116,516 American soldiers had given their lives.

William Mason’s 1926 book “Snohomish County in the War” has a list of the dead. That list takes up 11 pages. The roster includes 124 names of soldiers, sailors and Marines along with two Red Cross nurses. The vast majority of battlefield deaths involving local soldiers occurred in 1918.

On the eve of Memorial Day a century later, their sacrifices merit reflection, a reminder that ordinary people — the farmer, the logger, the sawmill worker — were willing to make extraordinary sacrifices.

Ask around at the library, the Veterans of Foreign Wars and American Legion halls, or the local historical society. Reach out to the tribal curator or grassroots genealogist. They’ll do some digging and those names from long ago become stories.

Story behind the name

One hundred years after his death, Gay Jones’ name can be found on a business card in Elmer Johnson’s wallet. VFW Post 921 is named after Jones, and Johnson, the organization’s quartermaster, keeps the cards handy.

Jones is one of 81 names engraved in a granite monument that hundreds of people pass by on Friday nights during football season at Snohomish High School’s Veterans Memorial Stadium. They were servicemen from in and around Snohomish who died for their country. Fifteen names are from World War I.

His draft registration card said Jones was born 10 miles north of Monroe, that he had worked on a farm and had no dependents. His signature at the bottom of the card is written in crisp cursive.

His parents, Hugh and Lillie Jones, had two daughters, but Gay Luther Jones was their only son, according to the 1910 U.S. Census.

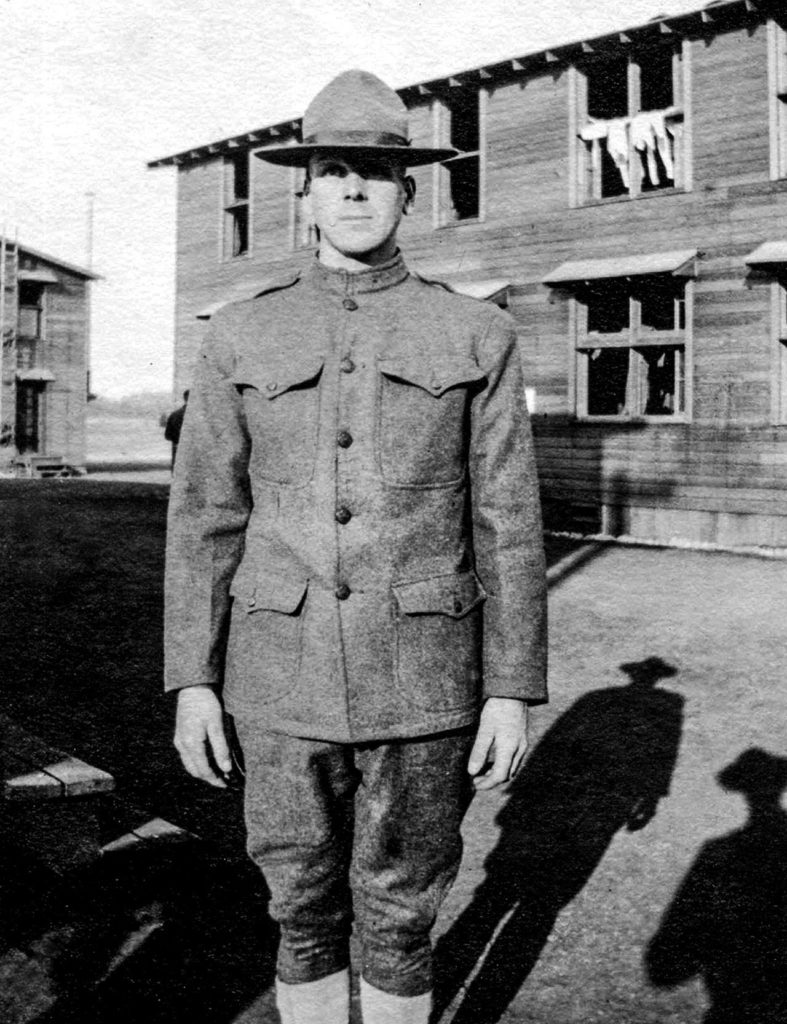

Pvt. Jones entered Camp Lewis May 25, 1918, and became a member of Company E 361st Infantry, 91st Division. Military records show he was aboard a ship barely two months later embarking from Hoboken, New Jersey, to the war in Europe.

On Sept. 26, he went into action in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, a critical but costly attack along the Western Front that helped bring an end to the war. He was killed three days later, one of more than 26,000 American soldiers lost in the 47-day campaign.

For a time, Pvt. Jones was buried in France.

His parents, like so many others, wanted him home. His casket sailed out of Antwerp, Belgium, on Aug. 5, 1921, back to Hoboken on its way to Snohomish.

On what would have been his 25th birthday, Pvt. Jones received a hero’s tribute in his hometown.

“The largest soldier funeral ever held in Snohomish was that of Gay L. Jones,” began a story five days later in the Sept. 23 Snohomish County Tribune.

A bugler played taps and a firing squad sent three volleys into the afternoon sky at the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery where his headstone is upright and readable today.

Arrangements that day were handled by the Earl Winehart American Legion Post in town. Winehart and Jones had been students at Snohomish High School. Pvt. Winehart was killed in action a week after Jones. He was buried in France.

These days, Earl Winehart’s name appears atop a giant downtown mural dedicated to veterans. It’s on the side of the American Legion Hall along First Street, a stone’s throw from the Snohomish River.

As it did on that Sunday afternoon 100 years ago, the Winehart post still watches out for Jones, maintaining the cemetery where he is buried.

Classmates and soldiers

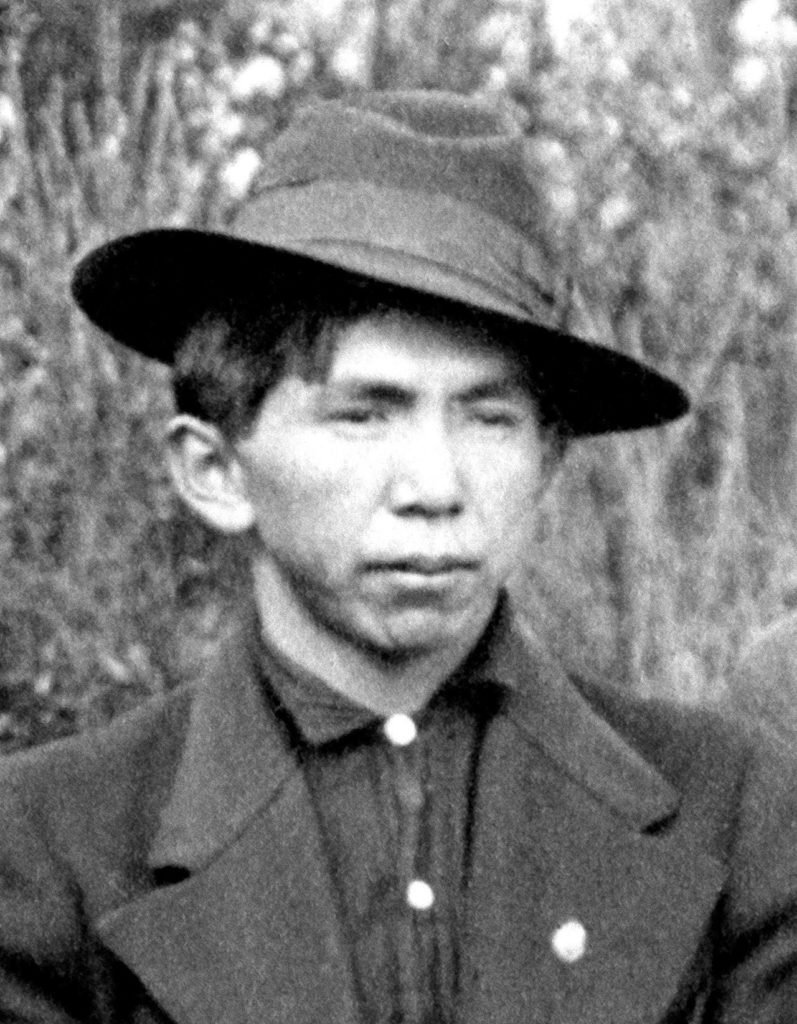

Their draft registration paperwork was filled out the same day, June 5, 1917, on the Tulalip Indian Reservation.

One was eager to serve; the other worried what would happen to his family if he was sent away.

Alphonsus Bob and Elson James were among the 17,000 Native Americans who registered to serve their country in World War I.

Bob, who had attended the Tulalip Boarding School and was later hired as its night watchman, grew impatient in the months that followed. He figured he’d try to volunteer for the Navy if the Army didn’t act soon.

“No boy answered the call of country with happier spirit or gladder heart” was how The Tulalip Bulletin in 1918 described his desire to serve.

James, who’d also attended the tribal boarding school, asked for an exemption from military service. He was the sole support for his mother, nephews and two sisters, according to his draft registration form.

Eventually, they were both called to duty. Bob was a private with Company D, 361st Infantry, 91st Division; James, a private with Company F, 30th Infantry, 3rd Division. Both would end up on the front lines and, in James’ case, beyond them.

On Oct. 12, 1918, Bob’s father received a telegram. Bob died in France Sept. 27, 1918.

“Few boys are held in more loving memory than that of our splendid boy, man and soldier Alphonsus Bob,” read a tribute in The Tulalip Bulletin.

James drew the admiration of commanding officers. Second Lt. Robert W. Wythes would call James “one of my best and most dependable men.”

On three consecutive nights, James guided soldiers to an isolated post in “No Man’s Land,” Wythes wrote. On the second night, the mission secured critical information about German occupation on the outskirts of a French village. James showed “exceptional skill, courage and coolness under fire.”

James that fall sent an undated postcard to his cousin Ed Percival back home. He wrote that he was among the soldiers following the German retreat into Germany and that the war would be over soon.

He was right. The fighting ended within three weeks of his late-night missions.

But they had taken a toll. James grew weak and feverish on a hike into Germany, likely from exposure. On Dec. 11, one month after the Armistice was signed, James died of pneumonia in a field hospital.

Today, Tessa Campbell is senior curator for the Tulalip Tribes’ Hibulb Cultural Center & Natural History Preserve. James is part of her family tree. He was her great-uncle, the brother of her grandmother.

For a long time, her family did not know where James was buried. In 2000, she was in France searching for his grave and other records. More than a decade later, her family encountered an Oct. 17, 1920, diary entry written by William Shelton, the last hereditary chief of the Tulalip Tribes. His diaries came to the Hibulb’s collection in 2013 and he chronicled life on the reservation from 1905 into the 1930s.

He wrote that Elson James’ body had come home on a train at 10 a.m. that day. “Big funeral this afternoon” with soldiers and Sunday school children among those to pay their respects, he wrote.

One hundred years after the soldiers’ deaths, passengers catch a Community Transit bus off Elson James Drive. South of Marine View Drive, children jump on trampolines in their yards along Bob Alphonsus Loop Road and glimpse Tulalip Bay.

Pursuing the past

Richard Hanks has been a journalist, archivist and community college instructor. He earned his doctorate in Native American history while in his 50s. He’s done extensive research on Southern California tribes, Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War. These days, he carries another title: president of the Stanwood Area Historical Society.

A few years back, he joined a community effort to build a veterans memorial plaza, which will be dedicated Monday on a lawn next to the Floyd Norgaard Cultural Center.

The memorial will have more than four dozen names, including 11 who died in World War I. Document by document, over months and years, Hanks has come to know the soldiers and their stories. He’s written short, compassionate biographies that have been published in the Crab Cracker, a twice-monthly magazine for Stanwood and Camano Island.

“I’m trying to put that human face back on people who are etched in marble,” he said. “I have sometimes spent two years on one particular soldier, trying to dig out a little bit more.”

In July 2015, he wrote about Jacob Tieseth, who emigrated from Norway in 1913 only to end up back in Europe as a U.S. Army field medic in 1918. He was posthumously awarded the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry in battle during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The citation from Gen. John J. Pershing described how Tieseth had come to the aid of the wounded before he, too, was shot and killed.

Hanks told of Red Cross nurse Emma Thorsen, who’d been raised in Silvana, graduated in 1915 from nursing school at Providence Hospital in Seattle, and was assigned to Camp Dodge, Iowa. More soldiers died from disease and other causes than on battlefields in World War I, including dozens from Snohomish County.

“Nurse Emma Thorsen may never have been close enough to the front lines in World War I to hear the roar of the guns, but certainly knew the moans of dying men,” Hanks related. “Their struggles became hers in the battle against the influenza pandemic of 1918.”

Thorsen, too, was stricken and died two weeks after the war ended.

There also was the story of Margaret Buli’s voyage to France 12 years after the war. The Gold Star mother went to visit her son’s grave. Albert Buli, a 24-year-old Marine private, died in the waning days of battle.

Of Pvt. Frank Hancock, a local farm boy who died in the Battle of Meuse-Argonne, Hanks describes the “slightly faded name printed on the cream stucco south wall of American Legion Post. 92” in Stanwood. The post is named in Hancock’s honor; Hanks calls him “Stanwood’s Symbolic Soldier.”

Also on the new memorial is the name Joseph E. Bruseth.

Head down to Arlington and Joseph Bruseth’s name can be found on a World War I memorial outside City Hall. Beneath an eagle and the words “For God and Country” are the names of “… THE BOYS OF THE TOWN WHO PAID THE SUPREME SACRIFICE IN THE WORLD WAR.” The ornate tribute was created in 1925. There was no way of knowing another world war would begin 14 years later.

A few miles south, volunteers at the Stillaguamish Valley Genealogy Society and Library are happy to spend a morning helping a visitor learn more about Bruseth and the seven other names on the bronze table. They seamlessly sift through old newspaper clippings and find military, census and ancestral records on the internet.

A colleague at the Stanwood Historical Society provided Hanks with correspondence received from one of Bruseth’s sisters.

It includes a Western Union telegram from Washington, D.C., sent to 4115 Rucker Ave. in Everett. It is dated 3:40 p.m. Dec. 12, 1918, a month and a day after the Armistice was signed. The telegram was addressed to Miss Eliza Bruseth and informed her that her brother was killed in action in early October.

She pressed for answers, sending a letter and photo of her brother to military higher-ups.

In October 1919, a year after her brother’s death, she received a letter from 1st Sgt. Albert Shad, who served with Company L, 111th Infantry, 28th Division. He described how Pvt. Bruseth and three other soldiers were assigned to venture into no man’s land to assess enemy strength. Less than five minutes after the patrol departed, three returned, including a sergeant who had been critically wounded.

Bruseth died where he was shot by a machine gun.

“He was given proper burial at the foot of the ridge by Chaplain Samoni with a wooden cross at the head of the grave with one of his identification tags attached to it,” Shad wrote.

Pvt. Bruseth would be buried again. His family saw to that — this time in the Arlington National Cemetery.

A brother, Peter Bruseth, also served in World War I stateside. He was discharged from the Army in July 1919.

Someday, Hanks would like to assemble all of the biographies of the Stanwood-area servicemen into a small book.

He hopes people will pay a visit to the new memorial in town.

And on Monday, as many people have the day off, he’d like to think they will remember.

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.