OLYMPIA — Following the second-driest spring since record-keeping began in 1895, and a heat wave that has killed at least 91 people, Gov. Jay Inslee declared a sweeping drought emergency for most of Washington.

At a news conference Wednesday afternoon, he and other state leaders offered a prognosis:

“It’s climate change,” Inslee said, again and again, using the statement as the punctuation to end each of his remarks.

With climate change, he said, Washingtonians have seen more wildfires and more smoky days. Roads have buckled from the heat. Shellfish have died off by the millions. There have been fewer berries, less wheat and poor grazing conditions. Glaciers are melting. People are dying.

“We have to recognize in some sense that this is the summer of climate change,” Inslee said.

And no, he quipped, air conditioners will not save us.

Laura Watson, director of the state Department of Ecology, said the drought came as a surprise. The winter brought “robust” winter snowpack in the mountains, she said, more than double the usual. But with the recent heat and lack of precipitation, that snowpack was wiped out in dramatic fashion.

A drought emergency declaration is issued when water supply is projected to be below 75% of average and poses a hardship to water users and the environment. The declaration allows expedited emergency water right permitting and allows the state to aid agriculture, protect public water supplies and boost stream flows to safeguard fish.

There is little hope for relief before fall. According to the Office of the State Climatologist, the three-month outlook for July through September shows increased chances of above-normal temperatures and below-normal precipitation for the entire state.

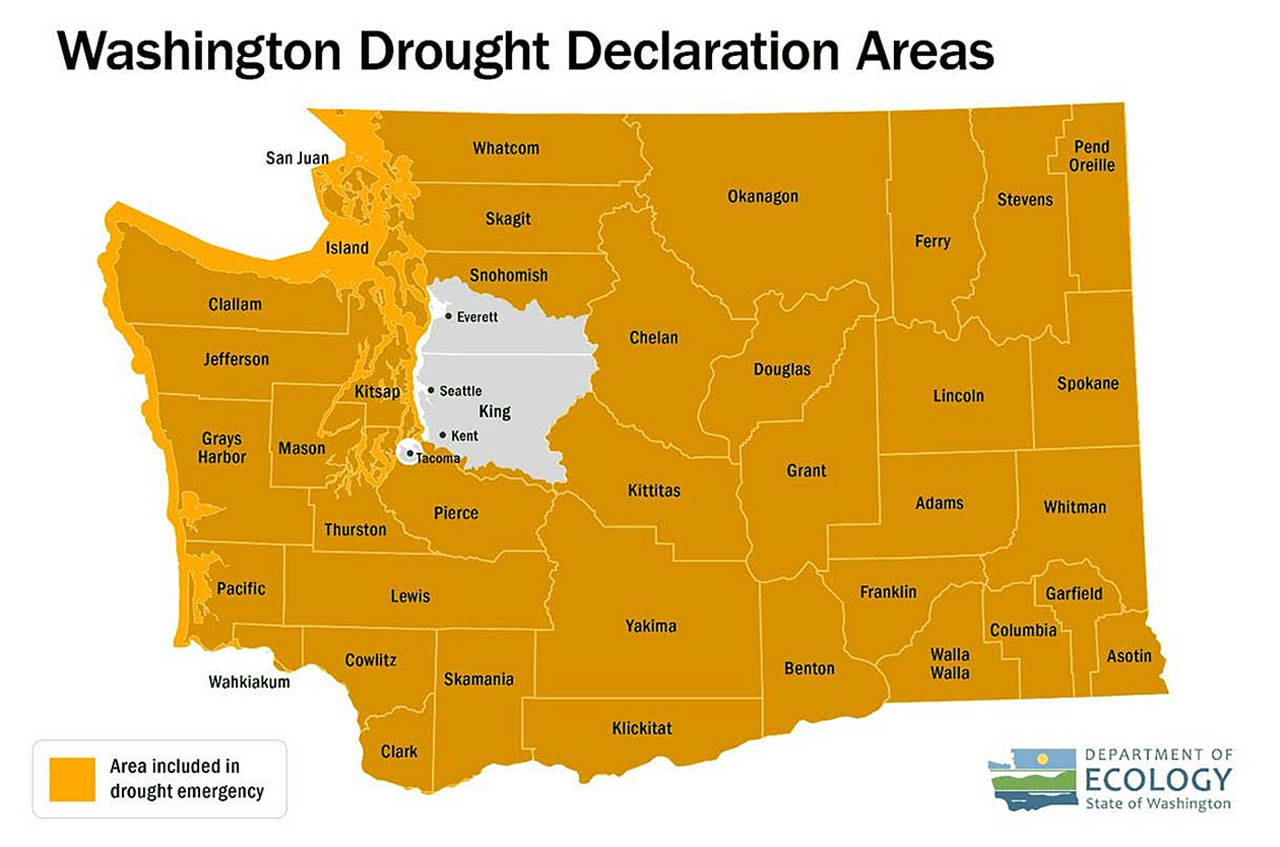

In Western Washington, there is an oasis, of sorts.

So far, most of Snohomish County has been spared from the drought, along with parts of King and Pierce counties.

How did that happen?

For Snohomish County, it’s simple: a big place to store water.

Actually, two big places: Spada Lake, with a 50-billion-gallon capacity, and Lake Chaplain, with a 5.2-billion-gallon capacity.

The Everett water system uses that water to supply an estimated 640,000 residents, about 75% of Snohomish County. It gets the water to them through a network of providers serving communities from Arlington to Mountlake Terrace and east to Sultan.

Even with record-high temperatures, Everett’s supply “continues to be in very good shape,” wrote public works spokesperson Kathleen Baxter. If it didn’t rain for the rest of the year, the city has enough in storage to meet demand, Baxter wrote.

At Spada Lake, keeping an adequate water level is a joint venture between the city and the Snohomish County Public Utility District, which co-own the reservoir.

Scott Spahr, generation engineering manager with the PUD, chalks up this year’s healthy supply to “a bit of fortune and advanced planning.”

The fortune comes from all the snowpack that piled up last winter. The depth at three measurement sites near Spada Lake was much greater than a year ago, with one site reporting the most snow since 2008.

Even when the snowpack melted, Spahr said, much of it drained into the reservoir, where it can still be used.

Spahr said the PUD treats the reservoir like a battery, and snowmelt is used to “charge” the water supply. If water levels become a concern, the agency scales back how much it uses for hydropower.

Watson credited Everett’s water storage for the region’s resilience in the face of the statewide drought. She said one way to prepare for future droughts is to build more water storage.

Still, she warned, the statewide drought serves as a “grim reminder” that water supplies face an increasingly uncertain future because of climate change.

The drought announcement isn’t the first emergency declaration of the summer. Last week, Inslee declared a wildfire state of emergency and announced a statewide ban on most outdoor and agricultural burning through Sept. 30.

This summer’s fire season is “likely to be the worst of the last five years,” said Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz. She implored the public to abide the burn bans.

She said that statewide there have already been more than 900 fires, with an estimated 219 square miles burned, just shy of the total land burned in all of 2019.

“If our new normal brings months without a drop of rain and one extreme heat wave after another, there’s no technology or amount of resources that will be able to match the on-the-ground reality our firefighters are facing,” Franz said.

The Associated Press contributed to this story.

Zachariah Bryan: 425-339-3431; zbryan@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @zachariahtb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.