TULALIP — When she was about 9 years old, Deborah Parker’s grandmother taught her how to hide beneath the dining room table.

Parker, then a tall elementary school student from Tulalip, crouched down beside her grandmother. The tablecloth draped over the edges, acting as a veil from the outside world.

“This is what we did so they wouldn’t take us to the boarding school,” her grandmother said.

“I just remember those thoughts of, like, how scary would it be for government officials to come and try and take your child, and you have no choice?” Parker said. “I can’t imagine.”

Parker, now the chief executive of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, is leading efforts to find records, graves and stories that expose the hard truths about the U.S. Indian Boarding School system.

On Wednesday, she spoke at the nation’s capital following the release of a U.S. Department of the Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, a key first step in a long-awaited reckoning.

“Our children had their own regalia, prayers and religion before Indian boarding schools violently took them away,” she said Wednesday. “… Boarding schools operated as a broad system with a singular goal: to strip us of our languages, identities and cultures, these life ways that have connected us to the land since time immemorial.”

The 106-page report identified 53 marked or unmarked graveyards where Indigenous students were buried. The initial investigation found at least 500 Indigenous children died in about 19 schools across the country.

From 1819 to 1969, kids as young as 4 were placed in one of at least 408 federally supported Indian boarding schools across the United States, where school officials forced the children to assimilate — often through violence, according to the Interior report released Wednesday.

“Rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; disease; malnourishment; overcrowding; and lack of health care in Indian boarding schools are well-documented,” the report says.

School rules were often enforced through solitary confinement, flogging, withholding food, whipping, slapping and cuffing, the report states. At times, older children were made to punish younger children.

“My house is almost on the (site of the Tulalip) boarding school — I can walk down the road and it’s right there,” Parker told reporters Wednesday. “Yet no one wanted to speak of the pain and the torture. We knew there was a little jail cell. We knew that the basement was where the kids were crying and wanting to go home. We knew that children didn’t get to go home. … We know that one of our young girls was sent to the basement and she was chained to a heater and beaten daily. We know others hid so that they wouldn’t receive the abuse.”

According to the report, the schools helped carry out two policies baked into the founding of the U.S. government: to take Native American land and wealth via treaties, and to eliminate the cultures of Native people.

‘Exterminate, eradicate and assimilate’

Congress enacted the Civilization Fund Act in 1819, as groundwork for a system of assimilation and cultural suppression labeled “education.” The stated mission of the act was “providing against the further decline and final extinction of the Indian tribes, adjoining the frontier settlements of the United States, and for introducing among them the habits and art of civilization.”

The federal government appropriated $10,000 each year to fund those goals. That money typically went to churches that would plant the seeds for federally run boarding schools.

In the late 1800s, Indian police began removing Indigenous children from their homes and placing them in federal Indian boarding schools, according to the Interior report.

“As the federal government moved the country west, they also moved to exterminate, eradicate and assimilate Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians, the languages, cultures, religions, traditional practices, and even the history of Native communities — all of it was targeted for destruction,” Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland said, fighting back tears at a press conference Wednesday. “Nowhere is that more clear than in the legacy of federal Indian boarding schools.”

Boarding schools “deployed systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” on Indigenous children, the report states. The school system largely focused on manual labor and vocational skills.

Indigenous children attended boarding schools for 10 months of the year. Federal records reveal the government viewed “disruption to the Indian family unit” as an integral part of federal policy to assimilate Indigenous children.

“The love of home and the warm reciprocal affection existing between parents and children are among the strongest characteristics of the Indian nature,” one 1904 document states, according to the Interior report.

According to local records, students learned how to speak English, grow food and log trees in school. They were forbidden from speaking their language or engaging in anything “Indian,” Tulalip elder Les Parks said.

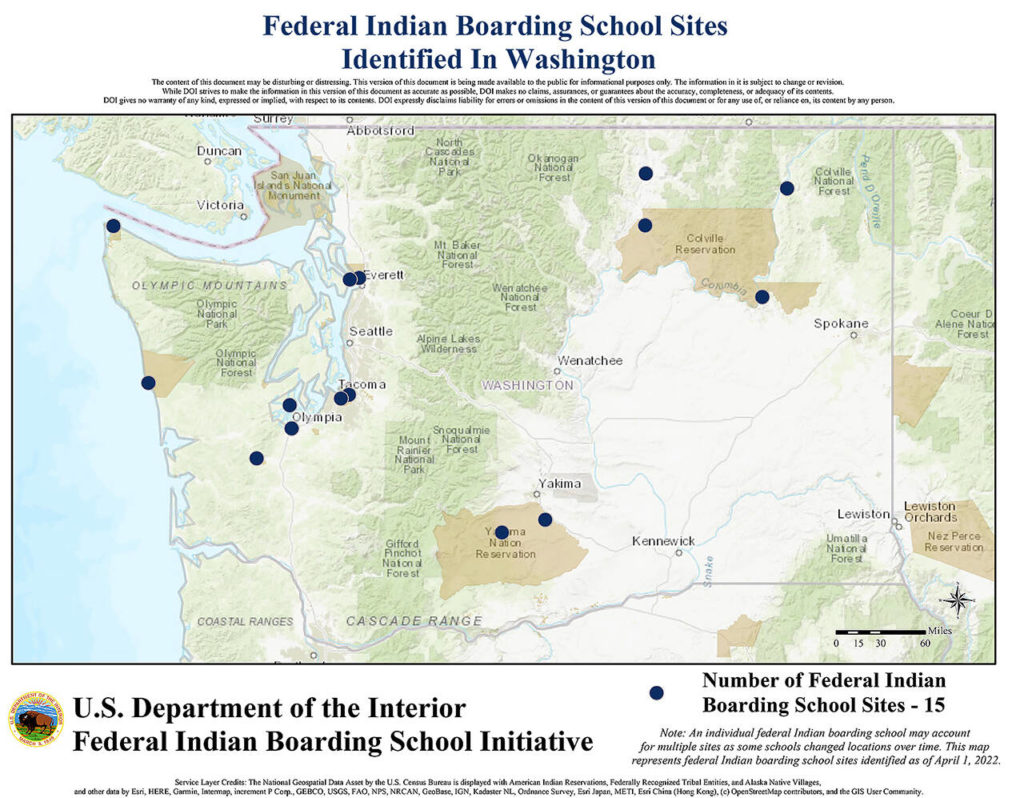

There were 15 federally funded boarding schools in the state of Washington, according to the Interior report. Two were listed on the Tulalip Reservation. The first was a Catholic mission school. It was transferred to federal government control around 1900, which counted as a second school in the new report.

The Tulalip Indian School only offered courses through the eighth grade. Many Tulalip teens were sent to the Chemawa Indian School near Salem, Oregon to finish their education. Others were sent to sanitariums or “hospitals.”

The Interior identified over 1,000 other institutions — including day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages and standalone dormitories — that may have played a part in the forced assimilation of Indigenous people.

The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative began just one year ago, by order of Haaland, the first Indigenous person to serve as a cabinet secretary.

For decades, Tulalip families and Indigenous families across the United States have grappled with intergenerational trauma resulting from abuse in the schools.

“There was an incredible amount of violence against my family members,” Parker told The Daily Herald.

‘I carry that hurt’

As the investigation continues, the Department of the Interior expects the number of known sites and child deaths to increase.

“Many died, often far from their homes and families,” Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland said Wednesday.

Boarding school survivors often don’t want to talk about the schools, said Teri Gobin, chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes.

“It left such scars on their life,” she said.

Many are now elders.

“A vast majority of us have our own family members who went to boarding school,” said Matt Remle, Native American liaison for the Marysville School District. “… Most of them don’t talk about it, don’t share about it.”

Indian boarding schools and their legacies — abuse, assimilation, death — touched at least one generation of every Native family in the United States.

The Interior report revealed attendance at each federal institution used for Indian education ranged from one to over 1,000 children, in the time frame from 1820 to 1932.

“The federal policies that attempted to wipe out Native identity, language and culture continue to manifest in the pain tribal communities face today,” Haaland said, “including cycles of violence and abuse, disappearance of Indigenous people, premature deaths, poverty and loss of wealth, mental health disorders and substance abuse.”

Studies have demonstrated boarding school survivors experience increased risk for PTSD, depression and unresolved grief. A “prevailing sense of despair, loneliness, and isolation from family and community are often described,” the new report says, citing a 2018 study of Northern Plains tribes.

“So much violence that impacted their self esteem, impacted their ability to work, to live, to parent,” Parker told the Herald. “And that’s impacted even me as a mother, as a relative, as a daughter. I carry that pain. I carry that hurt. I carry that. Just watching my relatives go through alcoholism, drug addiction — those are the social ills that we faced.”

With a $7 million investment from Congress, the Department of the Interior plans to produce a second volume of the report. Investigators identified 39,385 boxes of potentially relevant documents, or about 98.4 million sheets of paper, to analyze and possibly digitize for further research.

Interior officials will also soon begin a year-long cross-country tour to connect with boarding school survivors. The Interior department plans to create an oral history and help connect communities with trauma-informed support.

Newland also recommended that federal lawmakers fund Native language revitalization programs, promote Indigenous health research and recognize the generations of Indigenous people who experienced the federal Indian boarding school system with a federal memorial.

“Our children deserve to be found. Our children deserve to be brought home. We are here for their justice,” Parker said. “We will not stop advocating until the United States fully accounts for the genocide committed against our children. The time is now.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.