LYNNWOOD — Just before Marcella Giard Larson passed away at the age of 101, her daughter took a call from a stranger hoping to solve a mysterious death.

For a decade, cold case investigators tried to restore an identity to a man whose skull was unearthed by a roaming dog on a drizzly winter day in 1978, in a neighborhood off 164th Street SW in Lynnwood.

Last year the man’s ribs, vertebrae and clothes were exhumed from a waterlogged grave in Everett, with the hope of turning up clues. Up with the weathered bones came a rumpled flowery shirt, with tiny letters stenciled along the buttonholes: “Prescott Horace.”

Horace Jack “Dany” Prescott Jr. was Larson’s first cousin, who hadn’t been seen since the age of 49, when he walked off from a Seattle hotel in late 1976.

The centenarian from Stanwood gave a swab of her DNA to Jane Jorgensen at the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office on March 1.

Larson died two months later on May Day.

She did not live to find out her genetic profile became the final piece of a puzzle, confirming her cousin and the John Doe from Lynnwood were the same person.

In search of Horace

Horace Prescott grew up in a family of four with Nordic heritage, in what was a modest two-story Seattle home on Sunnyside Avenue, east of Green Lake and Ballard High School.

Census records show his elder sister Birdie Evelyn Prescott shared a name with her mother, whose maiden was Birdie Carolyn Husby. The son shared a name, too, with his father Horace Perrin Prescott Sr., an auto mechanic. On a spreadsheet from 1930, a Census worker scribbled that toddler Horace worked as a moulder at an ironworks, then crossed out the line and reassigned the job to a neighbor in his 40s.

The younger Horace took a nickname. Dany, 12, was the only son at the address listed in the 1940 Census. No one named Horace Prescott Jr. appeared in the Ballard High School yearbooks in the ’40s, but there is a Dany Prescott in three black-and-white photos: a sophomore grinning with his teeth, in a pale shirt collar poking out of a dark sweater; straight-faced with a wisp of a moustache in his junior year; smiling and clean-shaven with a fresh haircut as a senior.

His age lines up with the birth date for the missing man. He joined the Marines in the final days of World War II. His legal name appeared on a military fingerprint card. Japan announced its surrender two days before Pvt. Prescott’s first actual date in service, in August 1945. He sat in a military dentist’s chair weeks later. Dental records are often critical clues in cases of unidentfiied remains.

Soon after the grave was dug up in late 2018, Nancy Ward, of Kenmore, picked up a copy of The Daily Herald, and she read a front-page story about the mystery man. The article mentioned the name on the shirt, as well as the clues suggesting an alias.

“I walked around the house, and I kept saying to my husband, ‘Dany Prescott, Dany Prescott,’” Ward said. “I could just picture him sitting in the chair in our living room.”

In her youth she’d known a Dany Prescott, though she wasn’t sure of the spelling. He’d been a letter carrier who worked with her father at a post office in Ballard. He was tan, wiry, somewhat in shape from walking miles each day through Seattle for deliveries, with one shoulder weighed down by a hefty mail bag. He would stop at her family’s home on Dibble Avenue NW, to chat with Ward and her sisters.

“He was a very gentle soul. He was extremely shy of women, and my two sisters and I always intimidated the heck out of him,” Ward said. “ … It seemed like he felt rather surrounded by us.”

This would have been in the late 1960s, when Ward was in her early teens. He seemed about 6 feet tall to her. Her father, who held Dany in high regard, would refer to him as a young man. He had little to no gray in his hair. Yet he could have been 40. Ward never saw Dany out of his U.S. postal uniform, and almost always, he was sitting. As she spoke with a reporter, she looked at Dany’s high school portraits for the first time, in an article published on the internet.

“This is not the Dany Prescott I knew,” she said, a little deflated, in November 2018. “He had heavy eyebrows and full, full sad eyes.”

She studied the face closer, and noticed some of his traits seemed to match the man she’d known.

“I just can’t say for sure that these pictures are him at all, except the one on the very right,” she said.

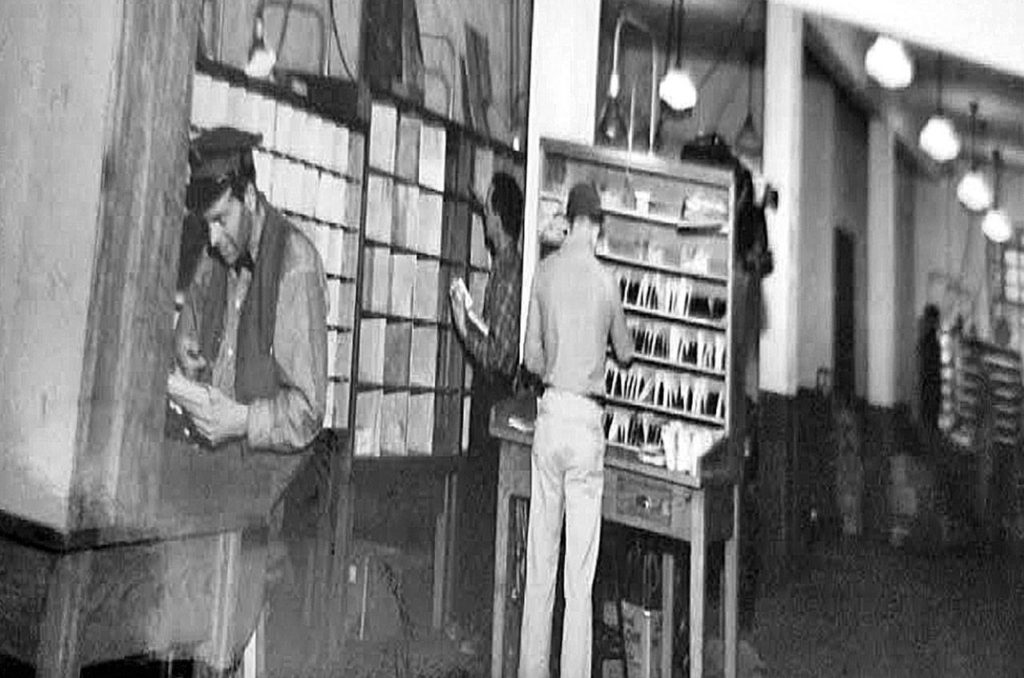

She’d known Dany Prescott as a grown man. In these photos, he was just a kid. Ward rummaged through a cedar chest where she kept her sister’s doll clothes and pictures that date to the early 1900s. In a bundle, among priceless photos she’d never seen before of her parents at a party, she made an unexpected find. There was Dany Prescott in a cap and vest, stooped over on a stool, sorting letters at a desk, probably putting them in order by address, Ward said.

“You could’ve just knocked me over with a feather,” she said.

Ward sent the picture to authorities.

She does not know why or how her family fell out of touch with Prescott. Her father never talked about him as having mental problems, but sometimes he’d travel to Tacoma for unspecified treatment through Veterans Affairs, Ward said.

Authorities know Horace Prescott Jr. had diagnosed mental illness. He spent time in military hospitals, like the man Ward had known in Ballard. How his illness manifested in his daily life may be lost to time, but police reports show Horace Jr. tended to wander.

Sometimes, Ward said, Dany would just disappear.

“That was one reason my dad was always so glad to see him,” she said, “because he would just go away.”

In search of a name

In his 40s, the disabled Marine veteran resided at a Seattle hotel, living off his retirement income. One day his father reported it had been six months since Horace Jr. picked up his check.

The Seattle Police Department took the missing person report. He’d last been seen Nov. 15, 1976.

Horace Sr. told police that his son would often leave without taking any kind of identification.

The first human remains were found on Jan. 4, 1978, in a yard along what was a rural street back then. Today the spot is neighbored by a busy thoroughfare, cookie-cutter apartments, a sprawling maze of stores — a Fred Meyer with a gas station, a Five Guys, a MOD Pizza, a sushi bar and so on.

As developers churned up the earth that spring, surveyors found a jaw bone, ribs, backbones, hip bones, dark blue dress pants, an off-white shirt and a blanket. All of it, except for a set of deer bones, appeared to belong to the same man. There was no sign of trauma other than a healed head injury.

The case was filed as an apparent natural death, with little else to go on. Most of the bones were buried in June 1978. The skull was placed in a bucket — then forgotten for decades, until an investigator carried out an inventory of unidentified remains at the medical examiner’s office in 2009.

State forensic anthropologist Dr. Kathy Taylor examined the skull and concluded it belonged to a man of European descent, who was over the age of 40. The case went cold again, until sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf took another look with Jorgensen in 2017.

At the time it was one of about a dozen cases of human remains that sheriff’s detectives hoped to identify. (Some of those have since been solved.)

As the investigators waited to execute an order to dig up the grave, they found a note in the case file with handwritten words, “John Doe No. 1 – 78.” Underneath that, “Horace Prescott.”

Jorgensen worked with Oregon genealogist Deb Stone to uncover family records and retrace branches of Prescott’s family tree. But his mother died in 1968. His father died in 1989. His sister died in 1994.

Meanwhile, investigators obtained the dental records from 1946 through NamUs, a national missing person database. Last year Dr. Gary Bell, a forensic dental expert, reviewed the records to compare them with the seven teeth remaining in the skull. Six of them had dental work.

Bell couldn’t say for sure it was Prescott. A lot can change in a man’s smile in three decades. But the dentist didn’t see any reason to rule him out.

A forensic artist reconstructed a rough version of the Lynnwood John Doe’s face, by sticking rubber pegs on bone and extrapolating his facial structure. The drawing bore a resemblance to Prescott, both in high school and at the post office.

Investigators sent remains to a lab that was able to extract DNA for comparison to other family, if kin could be found.

Earlier this year, the medical examiner’s office finally contacted two fairly close relatives: a second cousin on the father’s side in Oregon, and on the mother’s side, 100-year-old Marcella Larson in Stanwood.

Larson’s daughter Marcie Tepley recalled around the age of 7, she met an aunt named Birdie Husby. She remembers a train ride to Seattle, sitting on a bed to talk with her auntie, and not much else about her.

Tepley, 74, never saw Birdie’s son Horace Jr. Their families almost never interacted. The Husbys were early settlers of Stanwood. The name was so common there, Tepley said, it confused the mail carriers.

Tepley has an unlisted phone number. To find her relation to Horace Prescott, you have to leap across many Prescotts and Husbys. She was surprised to be found through Ancestry.com. She gave the investigators a surprise, too, when she said her mother was living at a senior home in Stanwood.

“They assumed my mom had passed on, and they were shocked that she was alive,” Tepley said.

Another cousin of Tepley’s mother had kept family records.

“We always had to send him (a note about) every little baby that was born, and he passed two years ago, and nobody could find any of the stuff that he did,” Tepley said.

Cleaning out his home, relatives picked up a calendar with a family tree on the back, tracing the bloodline to the 1600s.

Tepley’s mother celebrated her 101st birthday weeks after giving a swab of her cheek cells. Larson’s sample arrived at a University of North Texas lab. The report was finished in October. To a layperson, it reads like a a letdown.

“The tests showed an association between the sample and Prescott’s first cousin, although the statistical data was too weak for a definitive identification,” according to a case summary. “However, the results of the comparison found that the samples were concordant and concluded that the 09SN0730 sample could not be excluded as a relative of Prescott’s maternal cousin.”

In other words, the lab could not totally eliminate a tiny chance that Prescott and Larson are not relatives. But in light of all the other circumstances — the name in the case file, the name on the shirt, the teeth, the report by the anthropologist, the timing of the discovery — investigators feel they now have ample evidence to prove this was Horace Prescott.

Associate medical examiner Dr. J. Matthew Lacy made the official call this month.

Next on the former John Doe’s strange journey is to be buried a second time, in Oregon, at the request of extended family on his father’s side. Except this time, instead of a tiny paper marker for a pauper’s grave, Horace Prescott will get military honors.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.