Editorial: Recognizing state history’s conflicts and common ground

Published 1:30 am Tuesday, November 18, 2025

By The Herald Editorial Board

We’ve seen in recent years the fraught debate over removal of statues and monuments that honored Confederate war figures and other problematic people in history. But even placement of new monuments to historical figures can pose problems of logistics and politics.

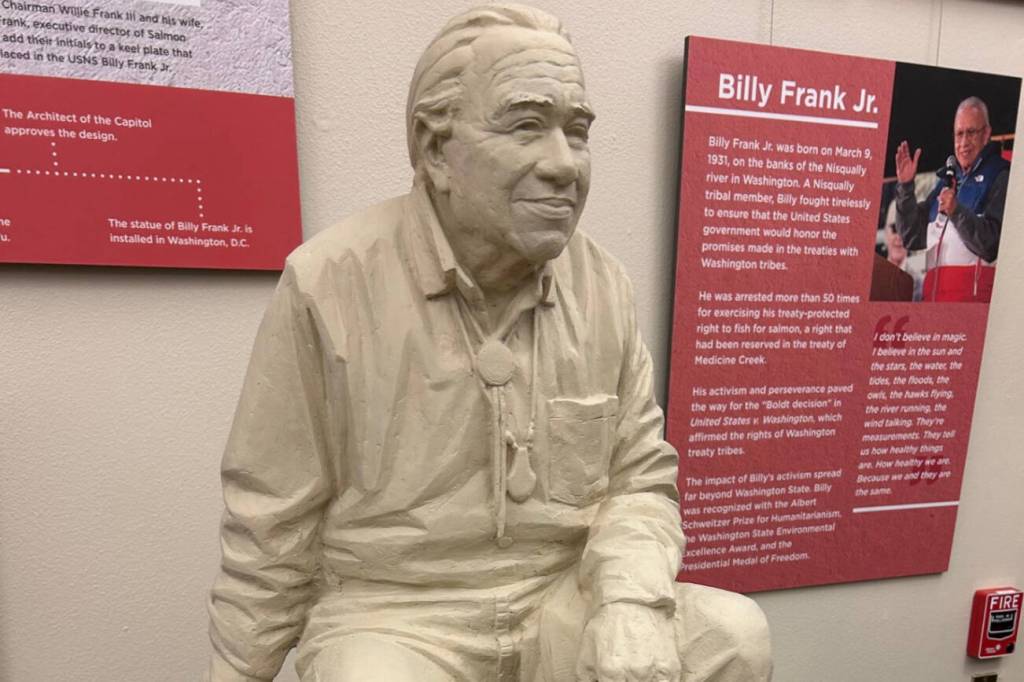

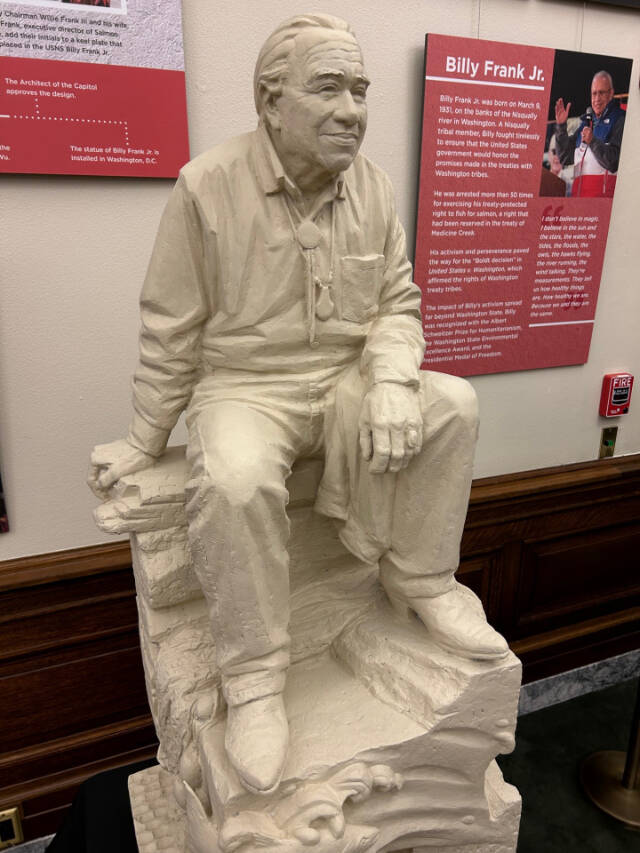

State officials now are debating placement of a new sculpture that honors the late Billy Frank Jr., a member of the Nisqually Tribe and chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission for most of its first 30 years, forcing a decision on the placement of at least one of two other sculptures that honor historical figures Marcus Whitman and Mother Joseph, both pioneering missionaries who came to what would become Washington state.

The Whitman sculpture, with its stone base is 11-feet tall and weighs 9,144 pounds, honors the physician and missionary who established a Christian mission in 1836 near present day Walla Walla on land of the Cayuse tribe.

It currently stands in the Capitol’s north portico, near where state officials had envisioned placing a new bronze sculpture — one of a pair that will soon by cast — of Billy Frank Jr. Along with the statue destined for the state Capitol, a second will be cast that will stand in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, which features two sculptures of historical figures from each of the states, currently Whitman and Mother Joseph.

Among those who first called for Frank to be honored in state legislation in 2021 was Lt. Gov. Denny Heck, who regularly walked by the statues in the U.S. Capitol during his tenure in Congress. During a legislative committee hearing when the sculpture was first proposed Heck said Frank described himself as developing from a “getting-arrested-type guy to a consensus builder,” as he pushed for tribal fishing rights, leading fish-ins and demonstrations that eventually led to the 1974 Boldt decision in federal court that affirmed tribal rights to salmon, steelhead and other fish and established the state’s Indian tribes as co-managers of the state’s fisheries.

Heck, along with the state Capitol Committee, now have the delicate task of finding a place of honor for Frank’s sculpture in the state Capitol while still paying respect to a state pioneer, albeit one with a history complicated by his drive to Christianize and “civilize” Indians and the relationships with tribes near his Walla Walla mission. Those relationships started cordially but deteriorated, as an account by History Link reports, in the face of mutual distrust, leading to the deaths of Whitman and his wife and 11 others in an attack by members of the Cayuse tribe on Nov. 29, 1847.

While Frank’s sculpture will replace Whitman’s in the nation’s Capitol, state committees and officials appear committed to rearranging furniture rather than deposing Whitman from Olympia.

Yet, relocating the Whitman sculpture has proved difficult logistically and politically. Its more than four tons rules out relocation to the Capitol’s third floor to a prominent spot outside the House and Senate chambers, because of the costs of reinforcing the floor. Locating the sculpture outside of the Capitol’s south portico would require periodic waxing to protect it from the elements and would leave it more vulnerable to vandalism.

Willie Frank III, Frank’s son, and others have expressed “very strong feelings,” the Washington State Standard’s Jerry Cornfield reported last week, regarding Frank’s sculpture sharing the same space as Whitman’s statue. And Frank III’s proposal to move the statue to the Wa He Lut Indian School at Franks Landing on the Nisqually Reservation was met with objections from those, including Republican lawmakers, who want both sculptures to have prominent locations at the Capitol.

“We’ve got a lot of different points of view that are being brought here, and I am convinced that if we deal with one another respectfully, we can get to a point where everybody is going to be comfortable with what we do,” Heck said in a recent meeting of the Capitol Committee, which he chairs. Heck, himself, has suggested the Whitman bronze cede its current location to the Frank sculpture, moving it to the entrance of the Senate cafeteria, between the offices of the governor and lieutenant governor.

But that move itself will require a $35,000 structural analysis that might have to wait for the Legislature’s budget negotiations that start early next year.

Even if the Whitman sculpture is moved some distance from the Frank sculpture, a thought-provoking juxtaposition of figures and state history will remain. With some of the options under consideration, Frank’s bronze would be displayed next to that of Mother Joseph, who in 1856 lead a group of missionaries to the Pacific Northwest territories where she was the architect and supervisor of construction for 11 hospitals, seven academies, two orphanages and five Indian schools.

No objections to siting the Frank and Mother Joseph sculptures near each other were noted during a recent presentation before a joint meeting of the Capitol Committee and the Capitol Campus Design Advisory Committee.

A decision will have to come soon as the contract for the bronze castings has been awarded to a Seattle foundry, and the statue destined for the U.S. Capitol is set for delivery by next September, as the nation marks its 250th year.

Heck’s call for respectful consensus should remain the overreaching goal as a final decision for the placement of all three sculptures is made. That desire for consensus and respect for history itself honors Frank’s legacy.

Not placing Whitman and Frank in close proximity — yet retaining Whitman’s presence at the Capitol — respects family and tribal wishes while still giving each man’s place in history its due. At the same time, the joint placement of Frank and Mother Joseph retains the opportunity to spur conversations regarding both the conflict and common ground shared by the state’s Indian nations and those who settled here to create Washington state.

And it honors much of what Frank worked for throughout his life.

As represented in the recent documentary “Fish War,” which chronicles the struggle for Native American rights — as treaties such as the Point Elliott Treaty of 1855 had guaranteed — to fish in the tribes’ “usual and accustomed areas,” Frank and others worked tirelessly not just for federal and state governments’ recognition of the right to harvest salmon but to build consensus that has required efforts to protect watershed and other habitats that are in the interest of all in the state.

Each of Frank’s sculptures deserves a prominent place in both Washington capitols.