‘It hurts my heart’: WA West African center scales back amid fiscal shortfall

Published 1:30 am Saturday, November 22, 2025

EVERETT — The Washington West African Center has significantly scaled back its programs due to a funding shortfall.

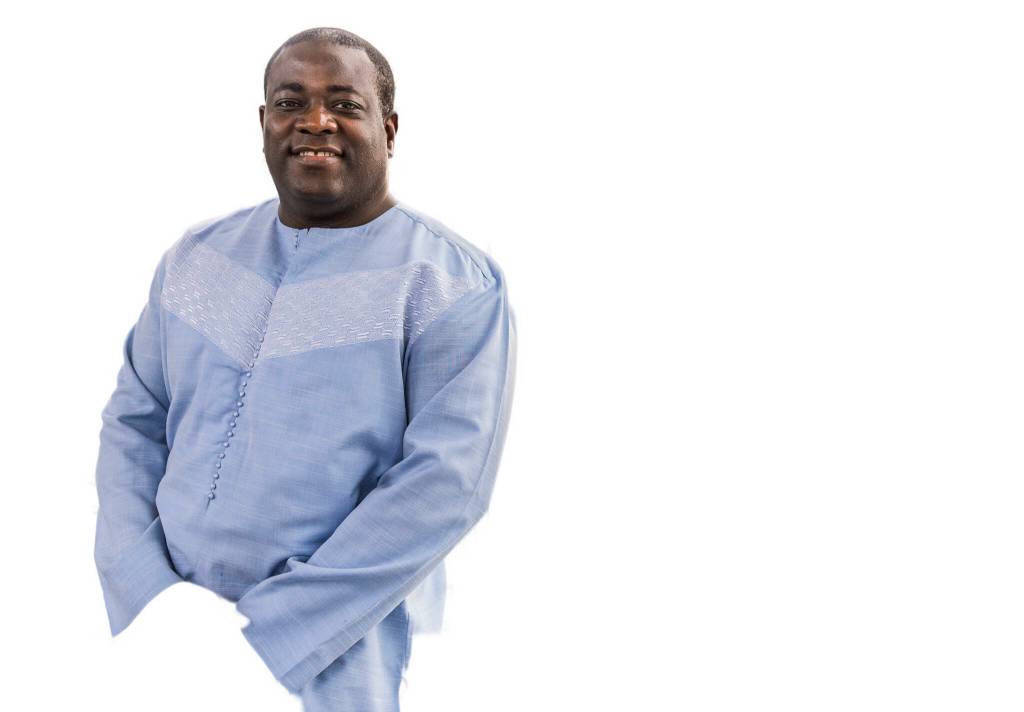

The shortfall stems from grants that have either been canceled or delayed this year, Executive Director Pa Ousman Joof said. The Lynnwood-based center’s budget for this year was $1.4 million, he said. It’s currently operating on $300,000.

The Washington West African Center provides free food distribution, housing assistance, transportation services, language classes and more to West Africans living in Washington. About 20,000 West Africans live in Washington, Joof said, mostly concentrated in Snohomish, King, Clark and Pierce counties.

“Quite simply put, we are the 211 and the 911 for the West African Community, where if they need anything, they just come to us,” Joof said. “If we don’t have it, we make a concerted effort to go find it.”

Joof is originally from The Gambia and founded the Washington West African Center in 2017. The idea for the center stemmed from his personal experience adjusting to life in the United States. In 2008, he was arrested and detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and had to wear a monitoring bracelet for nine months. He moved around the U.S. for several years in an attempt to find independence, he said. In 2015, he settled in Lynnwood.

“I decided to establish this to serve as a shoulder to lean on and create a culturally relevant hub where our community members can come and get access to services in a culturally relevant and dignified way,” Joof said.

In the past few months, the center has had to scale down multiple services, including its food distribution, housing services and English classes. It’s suspended its after-school and community garden programs. The center’s after-school program taught kids about African culture and tradition along with teaching life and career skills.

“Programs like this are definitely worth preserving, and I think that their importance can’t fully be stated, both on the impact of the kids’ lives and the parents’ lives, and even us as staff,” said Sahara Milam, who led the center’s after-school program.

The center saw an increase in funding after 2020, Joof said. Now, a lot of the funding is disappearing, he said.

“It had to take COVID and the death of George Floyd, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, for us to start having access to funding, visibility and access to sit at tables where decisions about our lives are made,” he said. “Our needs were there, our community’s problems were there, but we never had access. Post-COVID was when government entities started to realize that they can’t do this alone, and they need us.”

Although the center does not receive direct federal funding, Joof said federal policies are trickling down and affecting more local funding sources. When President Donald Trump took office, he signed an executive order to terminate government diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

“People and institutions are distancing themselves from our communities and people like us because they don’t want to be in trouble with the government,” Joof said. “They do not want to lose licenses, they do not want to lose funding, etc. and that is what is making it harder.”

Some grants operate on a reimbursement-based system, where the center must fully implement a program before it receives funding. Some reimbursements have been delayed, Joof said.

“It’s just hard for communities like us to keep up with because I need constant cash flow to be able to provide all these services that I’m providing for the community,” he said. “And it’s not happening.”

The center partners with local African restaurants to provide culturally relevant food to the West African community. Until this month, they held a food distribution event every two weeks. Now, they’ve scaled it down to once a month. The change came as local food banks are struggling due to rapid increases in demand.

The center also provides housing services for people who don’t have a place to stay, such as domestic violence victims and newly arrived migrants. One of the center’s biggest achievements, Joof said, is its master leasing program, which provides transitional housing and wraparound services while people work to secure work permits and jobs.

“Even when our community members apply for housing through the conventional ways, they are usually denied because there are several barriers against them,” he said.

The program is currently housing over 30 people and has housed 60 people over the past few years. Recently, they’ve had to scale back the program.

The center has also suspended its tailoring classes and moved its English classes online.

“Losing those programs is definitely worrying,” Joof said. “Losing the trust of the community is worrying.”

Some volunteers and staff members have seen their hours cut because of the financial challenges, with some going from 30 hours a week to less than 10.

“Nowadays, I’m only working eight hours or maybe six hours a week,” said Zenaboub Hayatoul Nourd Soumahoro, media assistant for the center. “It’s affecting my mental health.”

In a letter to local businesses, Joof called the center’s financial situation “a state of emergency.” The center is asking for donations and will hold a fundraiser event in January. Joof said he will reinstate programs as the center receives more funding. Washington West African Center is accepting donations at its website: wawac.org/donations/donate.

“It hurts my heart that the gains that we have made in the past five years are all being lost based on the current realities that we are faced with,” Joof said.

Jenna Peterson: 425-339-3486; jenna.peterson@heraldnet.com; X: @jennarpetersonn.