OTTER ISLAND — This is what nature intended.

Lush vegetation to either side of the brackish channel called to mind the Deep South bayou country, if only for lack of comparable landscapes.

This certainly wasn’t Louisiana. There were no live oaks with Spanish moss, alligators or copperheads. This was the Snohomish River estuary.

On Otter Island, one of the few largely intact pieces of natural tidal marsh between Everett and Marysville, spruce trees grow stunted amongst Oregon grape, salal and sedge. One April morning, clouds filtered the sun, almost hinting at a rainbow. Bald eagles watched stoically from branches high above. Mallard ducks, mergansers and blue herons occasionally flapped by below them.

The water, however, held the most significant sight for a group of habitat and floodplain experts poking around the islet on an aluminum-hulled boat. Thousands of juvenile chum salmon parr, no longer than a pinky finger, darted through submerged grass along the near-pristine banks. In the months ahead, their salmonid relatives, the endangered Chinook, would arrive from upriver.

“Otter Island is just a gem,” said Mike Rustay, a habitat biologist for Snohomish County. “It’s sort of right at the heart of the estuary.”

People who have lived much of their life rushing past this landscape on nearby I-5 could be forgiven for being awestruck. It shouldn’t look exotic, but it does. Much of the area once resembled Otter Island, until settlers built dikes to convert the soggy, low-lying earth to farmland. By the early 20th century, that had happened throughout the Snohomish River delta, and the region’s other river systems.

Around the mouth of the Snohomish, about 90 percent of the estuary is thought to be cut off from tidewaters that historically soaked the land.

This patch of ground, apparently, proved too difficult to tame. Otter Island survived in a mostly wild state, while its neighbors did not.

Scientists believe development of the estuary destroyed ideal places for juvenile Chinook salmon to linger and grow, giving them a better shot at survival when they venture out to saltwater. Chinook, more than other fish, rely on these tidal zones during early stages of life.

“The forest wetland back in here is some of the habitat that’s most needed,” said Brett Gaddis, also a county biologist. “If we could snap our fingers, this is what it would all look like.”

An ongoing transformation

It might be harder than a snap of the fingers, but Gaddis and his colleagues are working to return another piece of the estuary to a more natural condition.

Across Steamboat Slough from Otter Island and its Sitka spruce, Mid-Spencer Island has few trees, other than some that county staff planted in the early 2000s.

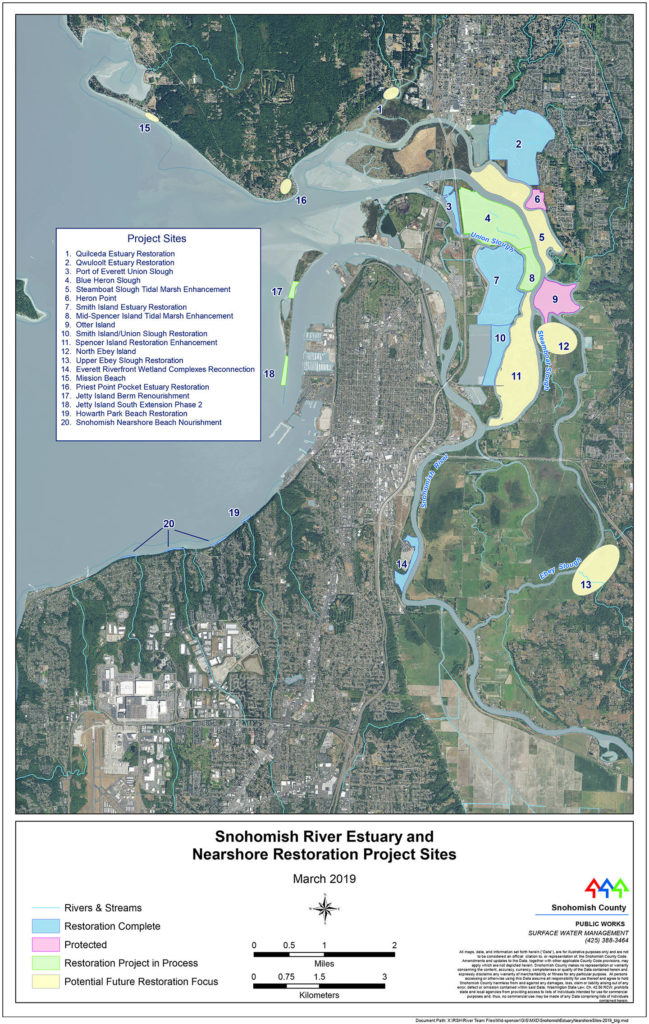

That’s the next piece of the habitat mosaic the county hopes to take on. It’s one of a dozen or more projects that various agencies have completed or will soon start in the estuary. The expensive re-engineering of the floodplain was spurred by the 1999 listing of Puget Sound Chinook as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Bull trout, another threatened species present in the watershed, also could thrive in the restored habitat along with insects, birds and other wildlife.

From what county staff can gather, the Mid-Spencer levees were built in the 1930s. There was a natural breach in the late-1960s. Water now flows through the dike in about four places.

“It’s been in the process of self-restoration,” Gaddis said. “The (tide) comes in and out of the older breaches. The remnant dike is not going away very fast.”

It’s far from what they’d like. A county contractor is preparing to start work in August to help the island reflood more completely. The plan is to make 16 new breaches and shave down another 1,000 feet of the dike to a lower elevation.

The county in April approved a $948,000 bid for the work. By October, when construction is expected to finish, about 74 acres should be exposed to the tides.

The goal is to increase juvenile salmon coming to the interior of Mid-Spencer.

The project won’t affect the nature trails on the south side of Spencer Island. It borders the Port of Everett habitat project known as Blue Heron Slough on the northern part of the island.

County staff consider Mid-Spencer more of an enhancement, rather than a full restoration like the massive Smith Island project on the other side of Union Slough. Completed last summer, after at least a decade and a half of property acquisitions and site prep, the work at Smith Island flooded more than 377 acres.

Smith Island brings the region closer to a goal of restoring more than 1,200 acres of estuary outlined in a 2005 salmon recovery plan for the Snohomish basin. Another step in that direction is the Tulalip Tribes’ comparably sized Qwuloolt Estuary, where dikes were breached in 2015. The port’s Blue Heron Slough, where work is supposed to start this year, is of a similar scale.

Throughout the spring, county staff documented hundreds of juvenile Chinook in Smith Island’s new tidal channels.

“We’re starting to see coho as well,” Rustay said. “We’re extremely pleased with the densities of fish we’re catching in there. And they’re distributed all throughout the site. It’s good to see.”

Qwuloolt suggests the eventual benefits could be even greater with time. A few years ago, there were essentially no salmon using the marshy area near Marysville.

“Now, there are anywhere between 10,000 to 100,000 — that’s just Chinook,” said Brett Shattuck, a restoration ecologist with the tribes.

Those numbers from 2017 are just a snapshot, what you might expect to see at any given time for much of the spring, Shattuck said. They exclude any chum, coho or other fish that might be passing through.

“Estuaries are really where you get the greatest bang for the buck when you’re talking about the recovery of Chinook,” Shattuck said. “If they get to a greater size, they have a much better chance of surviving once they get to salt water.”

Running out of time

The Snohomish is the second-largest watershed that drains into Puget Sound, behind the Skagit. Tributaries, including the Skykomish and Snoqualmie rivers, provide hundreds of miles of salmon-rearing habitat.

That makes it an attractive target for statewide efforts to revive Chinook. Other opportunities are scattered throughout the Sound, from Olympia to the Canadian border. Watersheds around Seattle and Tacoma have been paved over to the point where there may be little left to restore.

“The Skagit and the Snohomish are certainly some of the most important in the Sound,” said Erik Neatherlin, executive coordinator for the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office.

Despite getting more space in some Puget Sound estuaries, Chinook, so far, have shown few signs of rebounding. Neatherlin feels a sense of urgency. That’s true for the endangered salmon, and even more so for the critically endangered Southern Resident orca, which relies on Chinook as its primary source of food.

“Those projects that are hitting the ground are 10, 20 years in the making,” Neatherlin said. “We don’t have 10, 20 years out.”

Another 11 habitat projects around the state “could be built like that,” he said. But most would cost multiple millions of dollars, and they haven’t secured the money.

Chinook and other salmon species face challenges outside the estuary. They include culverts, water quality and survival at sea.

Still, Neatherlin can point to progress by local and tribal governments in the Snohomish estuary as a model for other parts of the state.

“I think we need to increase the urgency that we’re telling our story,” he said.

Back in the aluminum boat on the sloughs, Snohomish County floodplain engineer Lisa Tario was heartened by their work.

In the months since the tide seeped back into Smith Island, invasive Himalayan blackberries had started to die back. Native baldhip and Nootka roses grew in clumps. In the shallow waters, the ferment of decaying plants would provide food for insects, which in turn would feed fish and fowl.

The tangible results gave Tario hope, even if they may go unnoticed by the people living within view, on the edges of Everett, Lake Stevens and Marysville.

“I’m so choked up because we get to see it. We get to see what we’re doing,” she said. “… It’s not always visible, the enormous impacts that we’re having on the natural environment.”

Noah Haglund: 425-339-3465; nhaglund@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @NWhaglund.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.