EVERETT — Excavators chomped through the earthen berm at low tide.

A few hours later, saltwater flowed from Union Slough to flood former farmland on Smith Island for the first time in 85 years. Friday’s breakthrough marked a major milestone toward restoring chinook salmon habitat in the Snohomish River delta. Snohomish County has been at it since 2002, when it started acquiring land in the area.

“It’s an exciting project, a long time coming,” County Executive Dave Somers said. “It’s not only important for recreational and commercial fisheries of chinook (salmon), but for killer whales as well.”

The Smith Island Restoration Project originated from the 1999 listing of Puget Sound chinook as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Somers, a fish biologist by training, worked on salmon recovery planning in the early 2000s. He helped set restoration goals that the county, the Tulalip Tribes and other governments are now starting to realize.

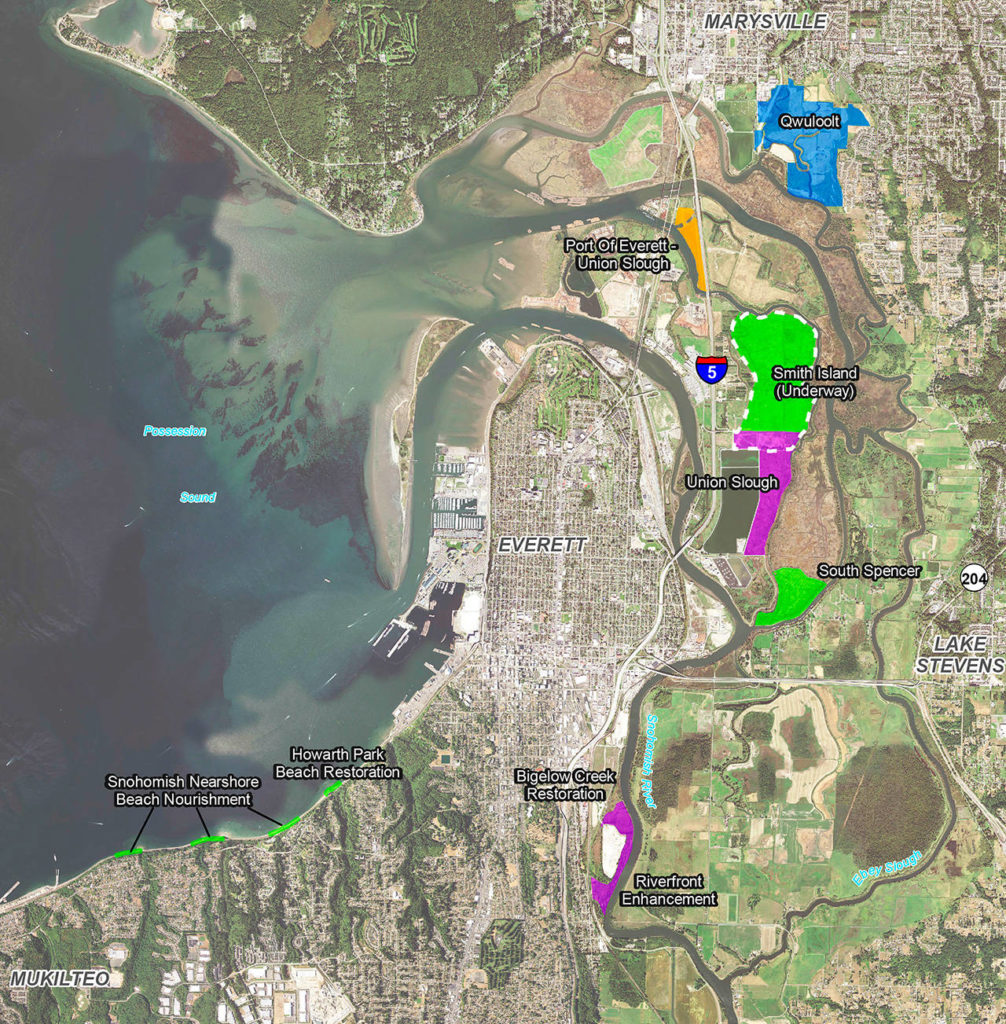

The biggest need was restoring rearing habitat for juvenile salmon before they migrate out to Puget Sound. The county project, along with work by the city of Everett, will provide 377.5 acres of new habitat south of Union Slough and east of I-5. That’s about a third of the land they’re hoping to restore in the Snohomish estuary. Projects by the tribes, the city of Everett and the Port of Everett are meeting the rest of the target.

When finished, biologists hope the reconstituted tidal marsh on Smith Island will host an average 250,000 chinook, juveniles and adults, throughout the year. It should help salmon during a crucial stage of life.

“The estuary is really the key part of the basin that’s been identified as a bottleneck,” said Mike Rustay, a senior habitat specialist with the county’s surface water management. “There is work to be done everywhere. The estuary is a key piece of that.”

Kurt Nelson, environmental division manager for the Tulalip Tribes, explained why.

“One reason we’re focusing on the estuary projects is because it’s critical habitat to out-migrating chinook,” Nelson said. “They’ll feed and grow. They’ll double in size if they’re here a month or two.”

When they arrive from upstream, chinook fry might be just over an inch long. When they head out to sea, they might be more than 3 inches.

The dikes built in the 1930s were supposed to keep Smith Island and other low-lying areas dry for farming. They also deprived young salmon of a place to grow and get stronger.

“They get flushed out to the saltwater sooner than is optimal, so they’re smaller and they’re not as well-fed and they’re more exposed to predators,” said Erik Stockdale, the county’s interim surface water planning manager.

Other fish species are expected to move in, including forage fish such as anchovies that marine predators feed on. Native plants, under the county’s vision, will reclaim the area and provide sustenance lower down the food chain.

“There’s a food web here — it’s all important,” said Aaron Kopp, a water resource engineer for the county.

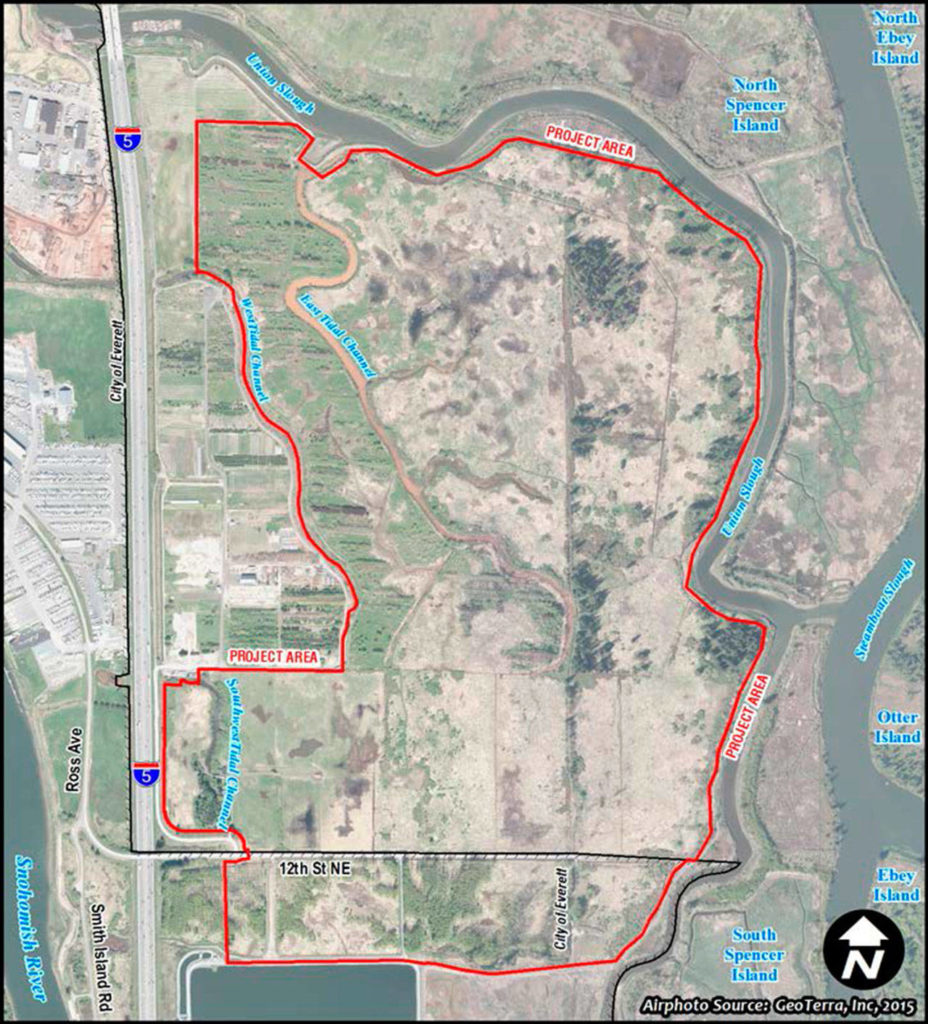

The area being flooded lies between Union Slough to the north and Everett’s wastewater lagoons to the south.

Contractors for the county got to work more than two years ago, building a mile-long dike that runs north and south. It sits closer to I-5 than the 1930s-era dike being taken out now. That allows water to inundate the land to the east.

The new dikes also should provide extra flood protection for I-5 and other nearby infrastructure, with the additional marshland possibly reducing the likelihood of catastrophic floods.

Heavy construction is expected to continue into October. That includes opening Friday’s breach to a total of 1,500 feet, plus another half-dozen openings elsewhere. After that, there are plans to finish a parking lot that people can use to access trails atop the dikes, similar to ones on nearby public lands such as Spencer Island.

A ceremony to mark the project’s completion is planned in September.

The restoration hasn’t come cheap. The budget now stands at $29 million, much more than the $13 million the county believed it would cost back in 2009. Of the total, $21.7 million is for construction.

Federal and state grants covered more than two-thirds of the cost.

The process wasn’t always pleasant. County Councilman Brian Sullivan, who represents the area, recalled years of packed hearings, pitting agricultural interests, which stood to lose ground, against fisheries, which were trying to reclaim it as tidal marsh.

“I’m glad it’s over,” Sullivan said. “We had hearing after hearing after hearing. There was a lot of confrontation over fish and farming.”

County government, Indian tribes, farmers and others helped bridge those divides through the process called the Sustainable Lands Strategy. That hasn’t erased tensions, though it does provide a forum to discuss them.

“It’s worked really well and the farmers have contributed greatly to help us do these restoration sites,” said Terry Williams, head of Tulalip’s treaty rights division.

Williams has had a hand in salmon habitat efforts for about 30 years. He said cooperation between the county and the tribes has never been better. He once employed Somers, when the future county executive was a biologist for the tribes.

The work on Smith Island is similar to a restoration effort the Tulalip Tribes completed about a mile away in 2015. The Qwuloolt project on Ebey Slough takes its name from the Lushootseed word for marsh. The primary goal was to restore habitat for wild-run chinook salmon. Other native fish, such as coho and bull trout, were expected to benefit as well. Scientists are gathering data on how fish are using the area.

Another restoration effort, an unfinished Port of Everett project, is between the ones by the tribes and the county.

How much more can be done?

“This is going to go past our lifetimes,” Williams said. “So it’s hard to guess.”

Noah Haglund: 425-339-3465; nhaglund@herald net.com. Twitter: @NWhaglund.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.