By Edie Everette / Herald Forum

Recently, at the grocery store, I ran into an acquaintance I hadn’t seen for a spell.

After asking about her, I asked about a mutual friend. “How is John?” I inquired, while her face melted into a compassion so pure that I knew instantly what it meant. “He has Alzheimer’s, and it has been a rapid decline.”

“Just two years ago,” she continued, “his wife and I were with him in Europe where he used his photographic memory and vast knowledge of World War II history to give us an amazing tour.”

After she left, I stood in the office supply aisle of the store taking deep breaths. I already had anxiety about dementia because at a Christmas party weeks earlier a man said he had run into my elderly sister and that she had not recognized him. Because he knew that my sister and I had cared for our mother when she had dementia, he looked me straight in the eyes and said, “are you scared?”

Heck, yeah, I’m scared!

I am now in my 60s and when I cannot remember a name or a word, my brain, wired for warnings, freaks. In a rush to make things right, I slowly go through the alphabet in my mind to see if that helps me find the mental file folder I’m looking for. After that, there are always search engines which can act for my brain like the extended-range fuel tank on my late father’s Porsche Roadster, an option for long-distance car racing.

It seems like a rite of passage these days, people being caregivers for parents who suffer from some form of dementia. While listening to someone telling me about their caregiver journey, I nod knowingly, saying things like, “Agree with everything they say, it creates less conflict.”

My mother’s cognitive decline was gradual. The hardest part for me was the inner anger I felt because she was not acting like a mother anymore. It was the same feeling I had as a child, when, after drinking a few Manhattans, my mother became a swarthy nightclub singer whom I did not recognize. The short of it is that even as an adult, as she became more like a child, I felt abandoned by her.

Getting over this “abandonment” or “disappointment” issue as a caregiver is something that cannot be forced. At least I couldn’t force myself to grow up and get a grip. Although I was loving toward her during her decline, I would get frustrated when, say, she’d leave the gas oven dial on with no flame. Finally, one day my brain re-aligned with life on life’s terms and my frustration brilliantly lifted to reveal inner peace and acceptance.

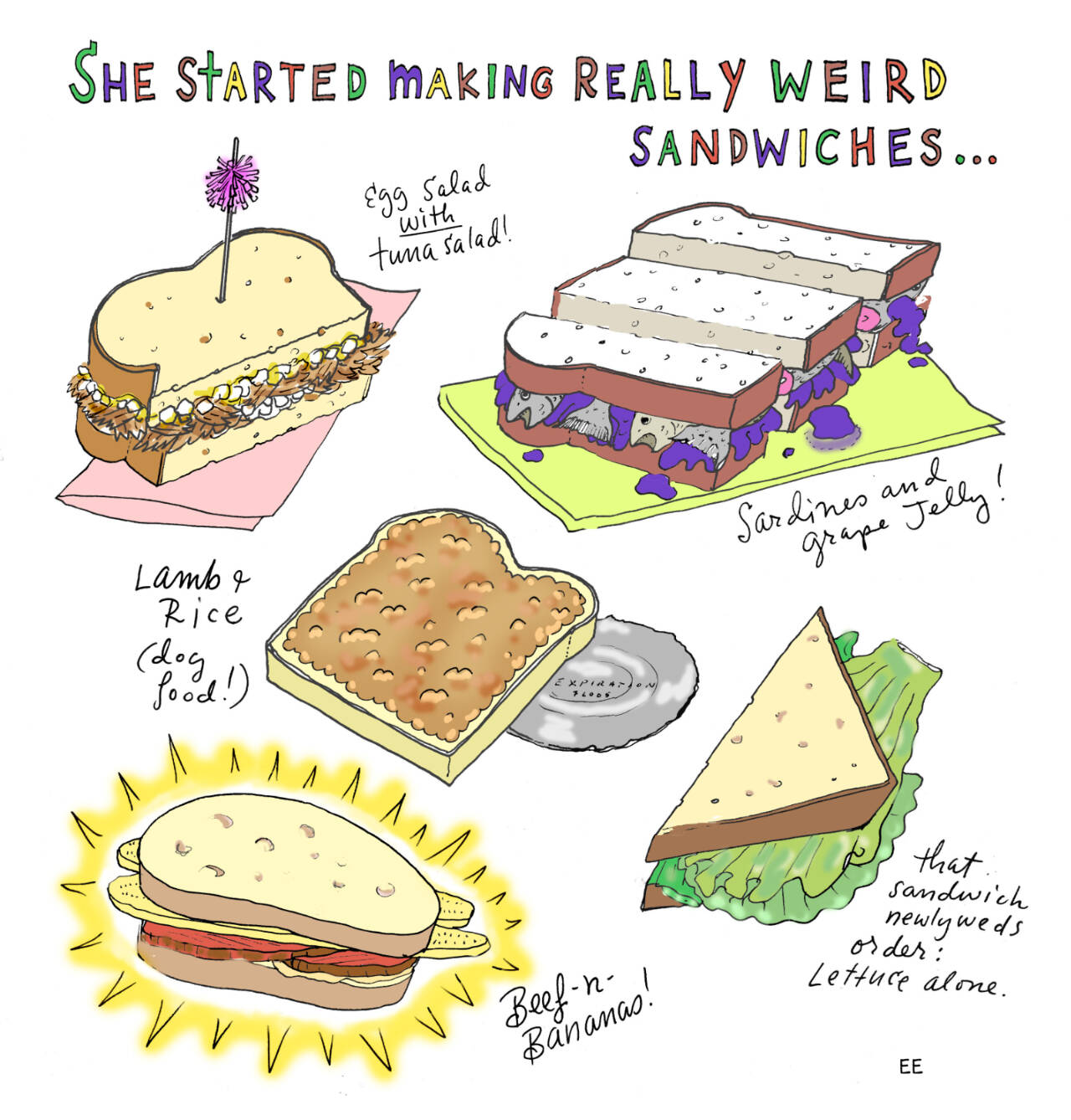

During this period with my mother, I was drawing comics about being a caregiver because … parts of it are funny!

For example, one day I was sweeping the kitchen while mom watched me from her bedroom. In my head I was getting all egotistical, like, “Wow, look at me cleaning the house so well!’”My mother suddenly said, “You are doing a great job … ” which puffed me up even more until she finished her sentence by saying, “… showing off.” Since then, my niece and I have used the term “showing off’ when we talk about doing housework.

It was amazing, though, that throughout my mother’s memory decline she never lost her sense of humor. I believe that humor in her was such a God-given force that nothing could stop her channeling it. She had the timing of Jack Benny, if anyone out there remembers who that was.

I have never finished my graphic book. I do that; I quit things. I know the book could have been good partly because my motive was pure: To help others by offering humor during a challenging time. I wanted other caregivers to realize that they have not been abandoned, that they are not alone: There are many of us out here, doing our best to hover in a state of grace.

Edie Everette is an artist and writer living in Snohomish County.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.