This might be the best Spirit of St. Louis replica ever made

Published 1:30 am Sunday, August 11, 2019

ARLINGTON — The details would make any dressmaker proud: French seams, a snug fit and an abundance of lift.

In high school, John Norman sewed his own clothes — purple bell bottoms, razzle-dazzle shirts.

Now he builds and sews his own airplanes. His latest is a replica of the Spirit of St. Louis, the single-engine plane that Charles Lindbergh flew non-stop from New York to Paris in 1927 in the first solo trans-Atlantic flight.

Norman, a retired Boeing mechanic, has built and restored 32 planes in the past 40 years as a hobby and through his business JNE Aircraft.

His Spirit of St. Louis replica, which has been called the most accurate ever made, will be on display at the Arlington Fly-In Aug. 16-18. A public flight is planned for later this month.

Norman, who lives in Burlington, has spent an estimated $1 million to build the replica, and devoted more than 10,000 hours to its construction.

“You build something like this and you hope it will fly,” Norman said.

Around the time Norman was designing those flare-leg jeans, a high school teacher, who was also a pilot, began offering an aeronautics class.

It was the vortex that drew all of Norman’s talent — welding, sewing, flying, dreaming. He first soloed in an airplane at 16.

Like other planes of its era, Lindbergh’s Spirit was covered in lightweight cotton fabric, “like your bed sheets,” Norman said.

For the replica, Norman took that same tack, sewing the wings, fuselage and rudder with an old Singer sewing machine.

“It took about 100 yards of cotton,” enough for 10 wedding dresses.

Whipping up a 46-foot wing that’s 7 feet wide, employing double-stitched French seams, isn’t much different than sewing a sleeve.

The pieces were loosely glued onto the frame, spritzed with water and left to dry — to achieve that Hollywood form fit.

Eight coats of butyrate dope stiffened and sealed the fabric. “It’s like model airplane glue,” he said, offering a sniff.

Mixed with aluminum paste, “dope” protects against ultraviolet light and gives the plane a metallic sheen.

“You wouldn’t believe how many people think it’s aluminum,” said Norman, who went through 40 gallons of the lacquer.

From 787s to a Ryan replica

Seven years ago, Norman sold a 1942 Hawker Hurricane, which he’d restored from the wreckage of three planes, to a buyer in Belgium.

The proceeds paid off the mortgage and then some.

Since 1990, he had wanted to build a working replica of the Spirit of St. Louis. This was his chance, said his wife, Heather.

Heather Norman is part of this story, too. She keeps the books, tracks his work hours and orders parts — “whatever needs to be done,” she said. They met more than 50 years ago while in high school on Lopez Island.

The Spirit, like the Hurricane, is for sale, too, and the Normans hope to clear $1 million before taxes.

Norman was still at Boeing, prepping 787s for delivery, when he received the first crate of aircraft tubing for his Spirit replica.

“I figured it would take me two or three years to build in my spare time,” said Norman, 66, who retired two years ago.

Ryan Airlines, a San Diego plane maker, built the original Spirit of St. Louis in 60 days, basing it on their model M-2 air-mail plane.

Rushing to meet Lindbergh’s deadline, they didn’t have time to draw a set of plans, said Norman, who spent as many hours researching the plane as building it.

Thirty years after the original plane was built, the lead mechanic drew a set from memory. They’re useful, said Norman, but they couldn’t fulfill the goal of creating a precise replica.

That would require more data and years more. In all, it took seven years to complete the replica, including three trips to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., to study the original.

He also worked closely with Ty Sundstrom, a California aviator who had built three Spirit replicas.

“I’d build a part and send photos to him,” said Norman.

They’d sit down with original photos and try to figure out dimensions of the different parts to exact scale.

They disagreed over the wingtip’s construction. Sundstrom was sure it was wood; Norman was betting it was metal.

With the Smithsonian’s consent, Norman solved the puzzle by touching a magnet to the original.

“It was metal,” he said.

Examining the original

There is no front window, no fuel gauge or brakes, and no glass in the plane’s two side windows, but that’s in keeping with the original.

“Lindbergh had to stay awake for 33½ hours,” Norman said. “We figure any glass would have made it too gassy in there.”

There are more than a half-dozen Spirit of St. Louis reproductions. Some use modern components or are based on another Ryan model, the Ryan Brougham — dubbed the Spirit’s sister ship.

In some circles, Norman’s version is being touted as the most accurate replica yet built.

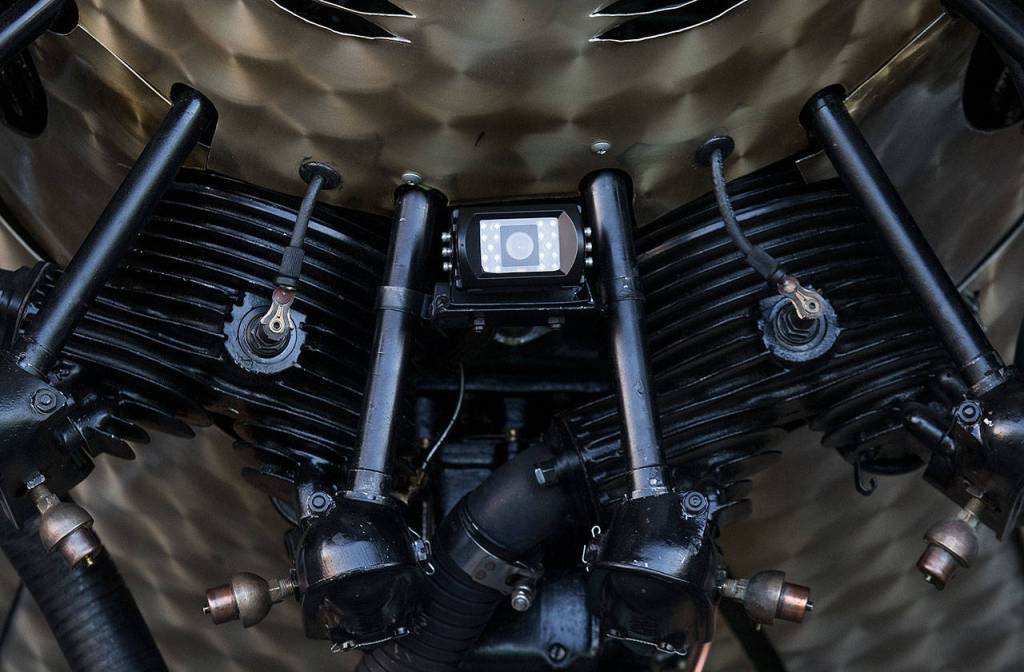

The radial engine, a Wright J-5 Whirlwind, and all the instruments match the original plane, the Antique Aircraft Association reported.

“John has even tracked down a flashlight of the same type that Lindbergh carried with him in May 1927,” the association said.

“I paid a guy in Guthrie, Oklahoma, big bucks — $30,000 for that engine — and then had to rebuild it!” Norman said.

He even bought a 1927 drill motor to recreate the whorls on the engine cowling.

Creating the curved cowling was like a tough gym workout.

“You take a hammer and beat the aluminum to make it bend,” he said. “I know, I’ve been working with sheet metal all my life.”

In 2015, the Smithsonian lowered the original Spirit of St. Louis to the floor for the first time in more than 20 years. Norman got permission to use a high-tech scope to probe the fuselage.

He found a patch on the main gasoline tank. He pinpointed the spot where “Peggy sat on the wing” and broke one of the wooden ribs.

According to the story, factory workers had a party after the plane was finished and someone, the alleged Peggy, was hoisted onto the wing, Norman said.

The scope also uncovered a problem that still plagues aircraft assemblers today — FOD, short for foreign object debris.

Concerned, U.S. Air Force officials halted deliveries of Boeing KC-46 tankers this spring after finding FOD in some of the aircraft’s closed compartments.

FOD can be wire, tools or candy wrappers inadvertently left behind during the assembly process. It’s akin to leaving a pair of snips inside the patient.

Norman’s scope of Lindbergh’s plane revealed a pair of pliers near the engine compartment.

The museum later determined it had been there since the plane’s assembly.

Even a four-ounce pair of pliers would have rankled Lindbergh, who nixed a fuel gauge, parachute and radio to reduce the plane’s weight.

Besides staying awake, Lindbergh’s challenge was toting enough gasoline for the 3,600 mile journey.

The Spirit’s five gas tanks carried nearly 450 gallons of fuel, weighing 2,745 pounds.

In the “The Flight,” a 2017 book detailing Lindbergh’s transatlantic crossing, Dan Hampton wrote that every ounce saved in the structure of the plane was an extra ounce of fuel that could be carried, and “a few more precious moments in the air could mean the difference between success and failure.”

“It cost Lindbergh $80 to fill up,” Norman said. “It would cost me $2,200.”

An amateur-built plane like the Spirit usually requires 40 hours of test flying before it can fly outside a restricted zone. Norman caught a break when the Federal Aviation Administration inspectors came to certify the plane as airworthy. They cut the 40 hours to a symbolic 33½ — the duration of Lindbergh’s flight.

Nice details, but would it fly?

On a recent Sunday morning, the Spirit of St. Louis replica rolled out of a hangar near the Arlington Municipal airport.

The engine’s exposed cylinders formed a black garland around a pointy nose. Its silvery-bronze cowling caught the light.

A knot of family and friends, which would grow to a crowd of 50, began to gather.

Norman fidgeted as he waited for his friend, Ron Fowler, an experienced pilot, to arrive from Lopez Island in his own plane.

Fowler had taxied the Spirit for nearly two hours the week before, testing the engine and controls.

On this day, he would climb into the small, cramped cockpit and take the yoke.

“There are other replicas out there,” Fowler would say later. “I think this is the most accurate one out there and by a substantial margin.”

When Fowler arrived, Norman turned serious.

“Why did I do it?” Norman said to his friend, realizing the gravity of the moment. “I want you to be safe. I can cancel it, I can cancel it now.”

“I’ve been around the airplane and John long enough to know — I trust him,” Fowler said later.

Fowler strapped himself into the pilot’s wicker seat, which, of course, Norman had woven himself.

The two worked in sync to get the engine to turn over. Like a Ford Model T that’s needs to be cranked, the Spirit’s propeller is also the starter.

“Hot. Crank. Hot. Crank.” They called to one another as Norman stepped forward to spin the 8-foot, 7-inch propeller.

The engine popped, sputtered and burst to life. Fowler turned the plane toward the runway.

The crowd followed.

At 7:20 a.m., the Spirit clawed and clattered its way into the sky for the first time.

“She’s up!” an onlooker shouted.

And then for 40 minutes everyone held their breath while it circled the Arlington airport, reaching an altitude of 2,300 feet and a top airspeed of 120 mph.

Norman, grinning like a sixth-grader after the successful flight, was happy and relieved. His replica of the Spirit had flown, his friend was safe.

“It was the most difficult plane I’ve ever flown,” Fowler said afterward.

How so?

Isn’t it obvious? There’s no front window. “You can’t see where you’re going,” he laughed.

In the weeks after the test flight, Norman was back at it with his wrench, tweaking the engine, adjusting the carburetor.

Fowler hopes to take it up for a second time later this month.

“I’m ready to go again,” he said. “It’s a piece of history I’m happy to be part of.”

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097; Twitter: JanicePods