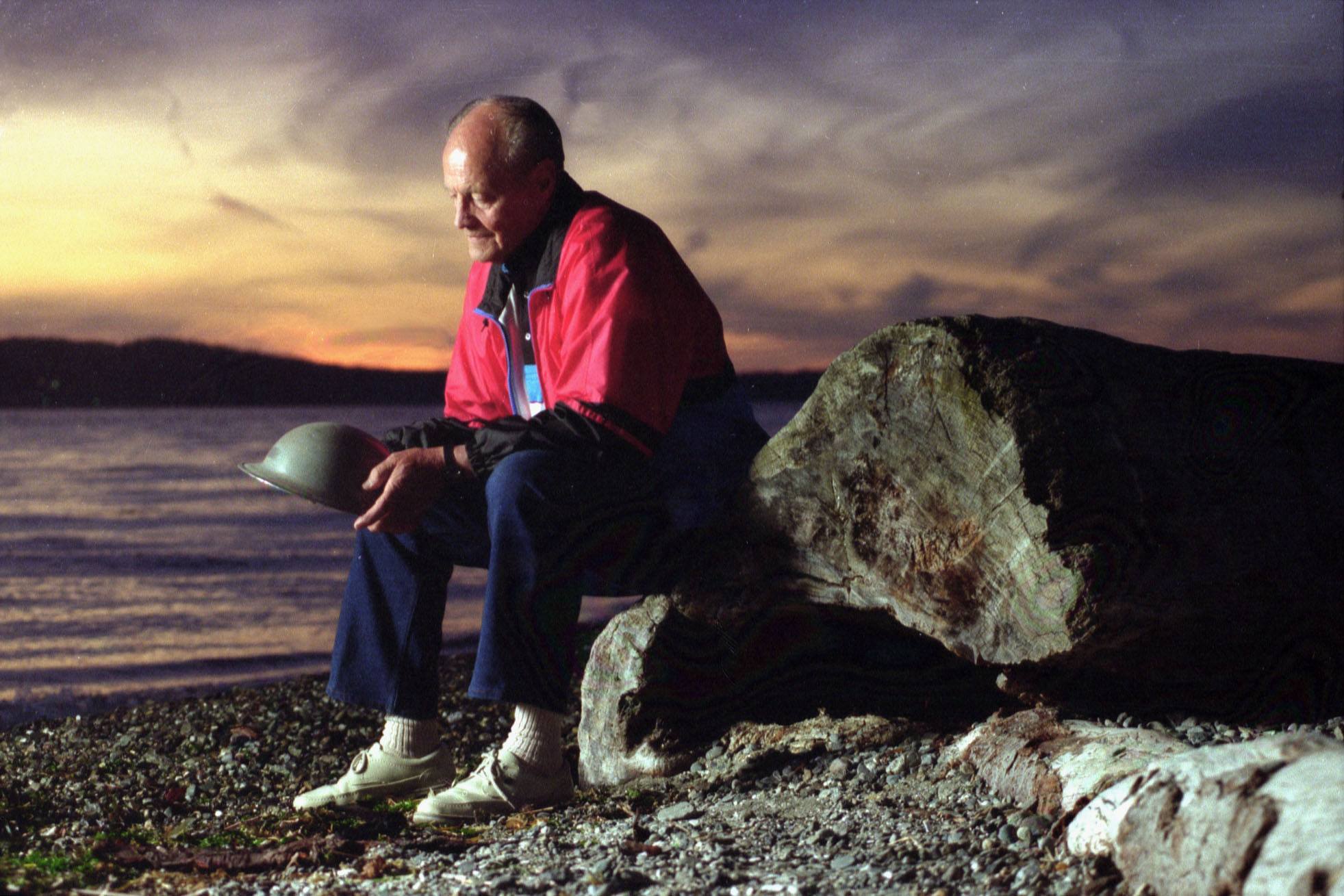

From the Daily Herald archives: Sept. 3, 1995

EVERETT — Jack Elkins, prisoner number 997, lay on a wooden pallet in a cold Yokohama warehouse and wished the moaning would stop.

It was near Christmas in 1942, and the young Marine was near death. His weight, normally 160 pounds, was under 100 and he barely had strength enough to walk.

The big, ugly warehouse, with the concrete floor and the chicken wire and stucco sides, had been converted into a prisoner of war camp. It was surrounded by a 8-foot-high fence topped with barbed wire and encircled by a moat. For most of World War II, this was Elkins’ home.

As he lay there with his hands between his legs to keep warm, his arms slipped clear through to the elbow. He looked down at his legs. They were less than three inches in diameter.

That first month in the Yokohama waterfront warehouse, 49 Allied prisoners from England and the U.S. died from pneumonia.

“It’s really a pretty terrible time when you’re like that,” he remembered. “You’re so sick and so close to dying, and you’d hear other people around you moaning and crying, and you’d wish they’d hurry up and die so they’d shut up.”

For Elkins, 72, the war meant months of intense shelling on Corregidor Island at the entrance to Manila Bay in the Philippines, followed by more than three years as a Japanese prisoner of war. It meant starvation, beatings and near death.

That first Christmas in Yokohama, with the help of a sympathetic guard, Elkins eventually recovered his strength enough to continue working forced labor alongside other prisoners and Japanese civilians in the Mitsubishi shipyards.

Most guards weren’t as friendly.

“Were you smoking?” another guard asked one night a few months later. He was looking at Elkins, who didn’t have much time to ponder his predicament. If he said yes, he’d be beaten for smoking. If he said no, he’d be beaten for lying.

“I wasn’t smoking,” Elkins said, as he stood outside in the chilly night air. The guard picked up a piece of firewood and struck him hard in the face.

“Were you smoking?” he repeated in Japanese.

“No.” Whack.

“Were you smoking?”

“No.” Whack.

After a half-dozen blows, Elkins was made to stand outdoors the remainder of that night holding a bucket of water in each hand. His only relief came when the guard looked away.

The next morning he grabbed his shoes and, with the rest of the prisoners, started walking the two miles to the shipyard to work.

• • •

Sometime in the morning of the day that Corregidor fell, a couple of Japanese bullets exploded in the dirt near Elkins’ face and he figured he’d finally been spotted.

It was May 1942, and Elkins had not yet been captured by the Japanese. He knew nothing of the awful camp that awaited him in Yokohama.

The young Marine, who had spent the last several hours in fierce nighttime battle, dove into his five-foot-deep foxhole and pondered his predicament. When you’re locked in combat, and the beach near you is lit up with bullets and murderous explosions, your options are limited.

Peering over the lip of the foxhole, Elkins figured, was suicide. So he ripped the pin from a hand grenade at his feet and sat there in that Philippine Island foxhole, waiting to hand it to the first Japanese soldier who wandered by.

The much anticipated Japanese invasion by 2,000 infantrymen had begun just after sunset on a warm May evening.

Elkins, who had left home to join the Marines, was 20 years old and armed with about 40 hand grenades, a Browning automatic rifle and 1,000 rounds of ammunition. His lonely foxhole was the farthest out on one end of the island. There were few American soldiers nearby for support.

Sometime after the enemy had landed, Elkins and another Marine quietly slipped along the island’s overhanging cliffs and stopped when they heard Japanese voices drifting up from the darkened beach.

Days earlier they had dragged several 30-pound bombs to the cliffs and now Elkins, a former high school football player, grabbed one, stood and heaved it end over end to the beach below. Thump. Nothing. He grabbed another and this time spiraled it out underhand. When the explosion cleared, it was quiet on the beach and the two American soldiers hurried away.

Later, huddled in the bottom of his funnel-shaped foxhole, he waited, his hand wrapped around the grenade. He picked up an old peanut butter can he’d been using to hold water, stuck his helmet on it and inched it up out of the foxhole. No shooting. He inched it up a little higher. Still quiet. Finally he put the helmet back on and eased up out of the hole.

Later that day, the battle unwinnable, the Americans surrendered and the prisoners, including Elkins, were told to line up and kneel. Nearby, Japanese soldiers in animated discussion debated whether to kill their prisoners or let them live.

As he knelt on that gravel road, Elkins realized that, for one of the first times in his life, he was at the head of the line.

Just like the foxhole, however, his options were limited.

• • •

A few months later, the young Marine, still wearing his tattered tropical uniform, shivered in the hold of a rusty steamer, along with about 600 others en route to their Yokohama prison camp. The situation was becoming unbearable.

There wasn’t room enough for everyone to lie down in the ship’s dark belly, and the temperature outside was dropping as they neared Japan. Once a day Elkins watched as a hatch opened and down came a wooden tub of rice. A while later it was lowered again, this time carrying water. While the hatch was open, the guards would pull out the dead and throw them overboard.

Those who had the strength climbed a ladder to the deck of the rolling ship, where they’d cling to a railing, using the ocean for their bathroom.

Some didn’t have the strength to climb the ladder. Joe Gear of Amarillo, Texas, was too sick to go below.

“He had diarrhea so bad there was no way we could take care of him,” Elkins said. “This fellow named (C.J.) Hanson and I, who were really good friends, laid out two planks, one on the bottom rail of the railing, the other braced on the deck, took off his pants and covered him with a poncho. Hanson and I would go up there and one of us would hold his legs up and the other would take a bucket of sea water and we’d wash him off. He laid up there on that deck all that time on that ship, two weeks. We’d take him up a little food, but not much, because we didn’t have much.”

When the ship arrived, the prisoners were unloaded and readied for transport to prison camp. All except Joe Gear.

“He’s close to death,” the Japanese informed Elkins and Hanson. “Leave him.”

And so they said goodbye, leaving their friend on the deck among the pile of dead who hadn’t survived the hard voyage.

“I’ll see you on Market Street,” Gear managed as Elkins and Hanson walked away.

• • •

He survived on prayer, mental toughness and a kind of orneriness that absolutely refused to provide his captors with satisfaction.

Over and over Elkins told himself, the score would never be even. After all, he reasoned, he had personally killed more than one enemy soldier during the Corregidor invasion. “They can kill me,” he thought, “but that’s only one.”

In the prison camp, he slept on a thin straw mat rolled out on the wooden pallet. His personal space was eight feet long and 30 inches wide, and he shared the warehouse with 500 others. The red stripe on his shirt told his Japanese captors that he was American.

Elkins became known as the camp librarian after he managed to scrounge three books that he read over and over until they were nearly memorized: “Hell on Ice,” “An American Doctor’s Odyssey” and a small book of works by Longfellow.

A chapter in the “Doctor’s Odyssey” was devoted to the bubonic plague and the kind of rat-infested squalor where it thrives. After reading that chapter one night Elkins, who hadn’t had a bath in two weeks, lay on his pallet and listened to the rat that came every night to gnaw on the tin food plate near his head.

“I guess I should have picked a different book,” he said 50 years later.

One memorable day during his long stay a new prisoner arrived with a treasure, a small tube of toothpaste. Elkins was brushing his teeth with his worn-out toothbrush out at an old water faucet when the soldier offered a dab.

“I couldn’t spit it out,” he said. “I hadn’t had anything like that in so long, and I thought it tasted so good. Ummm. If I’d had more, I’d of spread it on my rice.”

Another time, prisoners returning from another camp brought Hanson a letter. Amazingly, it was from Joe Gear.

“They’d unloaded him off the deck and laid him with the dead, and he’d laid there all that night and the next day until they came to take the dead to the crematorium. Then he started complaining. He was always complaining. You had to know him. He had a real way of doing it too, like, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ Anyway they decided he wasn’t dead enough and took him to a hospital and he wound up going all the way through the war. He survived the whole thing. I couldn’t believe it.”

Joe Gear died last year in Amarillo.

• • •

In the end, it was the American air raids and shelling that signaled the end of Elkins’ war.

He was in camp one day in 1945 when it was shelled by American ships stationed just off the coast.

The exploding 2,100-pound bombs obliterated part of the camp, killing some prisoners, but Elkins ran for the beach, where he dove between some big logs and watched.

In the confusion, he heard two Red Cross pigs die in the shelling.

As buildings burned and bombs exploded Elkins and a friend grabbed a knife, went back in and cut a big chunk off one of the pigs. His next stop was a shed that held the camp’s rice.

“I had about 10 or 15 fire buckets that I’d put in water and rice and a big hunk of pork,” he said. “When Hanson and my friends came back, I had the biggest meal for them. I was walking around with a stick, stirring the buckets.”

About a week before the war’s end, American planes began dropping food, magazines and candy bars to the prisoners. It was from one of those news magazines that he first learned of the atomic bomb. It meant very little at the time; just another weapon in an awful war.

It was also from one of those planes that Elkins had a close-up view of an American pilot, who threw packs of cigarettes out the cockpit and waved hello.

“Then I knew we were going to get out of this thing,” he said.

The day soon came when the Japanese guards laid down their rifles and walked away. The war was over. In the next 30 days, as he awaited the Americans, Elkins gained 30 pounds, liberating chickens and corn from the Japanese countryside.

“There was no retribution. If they (Japanese civilians) had any corn and we told them it looked good and we sure would like to have some, they’d fill half a sack fast,” he said. “They were afraid of our looks and also thinking that we might be vengeful, but that was the last thing on anybody’s mind.”

• • •

Like most former prisoners, Elkins still suffers from those years of rice, thin soup and, one summer, nothing but squash.

Handball, racquetball, vitamins and attention to his small leasing business in his Everett basement keep him busy and alert. Still, there are arthritis, emphysema and old ravages of beriberi and malaria.

A half-century later, there are other effects.

It was toward daybreak when the bombing and shelling on Corregidor stopped and, unbelievably, Elkins fell asleep.

A half-hour later he awoke as the sun rose and took a cautious look from his foxhole. About 40 yards away, four Japanese soldiers were making breakfast on the quiet, peaceful beach.

“I watched for a little while and decided when they were cleaning up their things that I’d better do something, because I knew their next project would be to find me,” he said.

So he grabbed his Browning, aimed and squeezed the trigger.

“I’m probably saying it for the first time, but when people say they want to go back to Corregidor, in my mind it’s a beautiful morning and the sun’s shining. The sand is pretty, the water’s blue and everything is like that. And then blood is spread out there and it’s red scarlet,” he said. “Those are the things that I see.”

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.