WASHINGTON — There have been very few truly memorable guerilla theater performances in the chamber of the House of Representatives during the past half century. What happened Wednesday quickly won a spot on that exclusive roster.

On a day with plenty of dramatic national political stories, including Donald Trump labeling Hillary Clinton “a world class liar” and Marco Rubio reversing his Senate retirement plans, a clutch of Democrats who are usually disregarded as policy-making afterthoughts easily managed to steal the show.

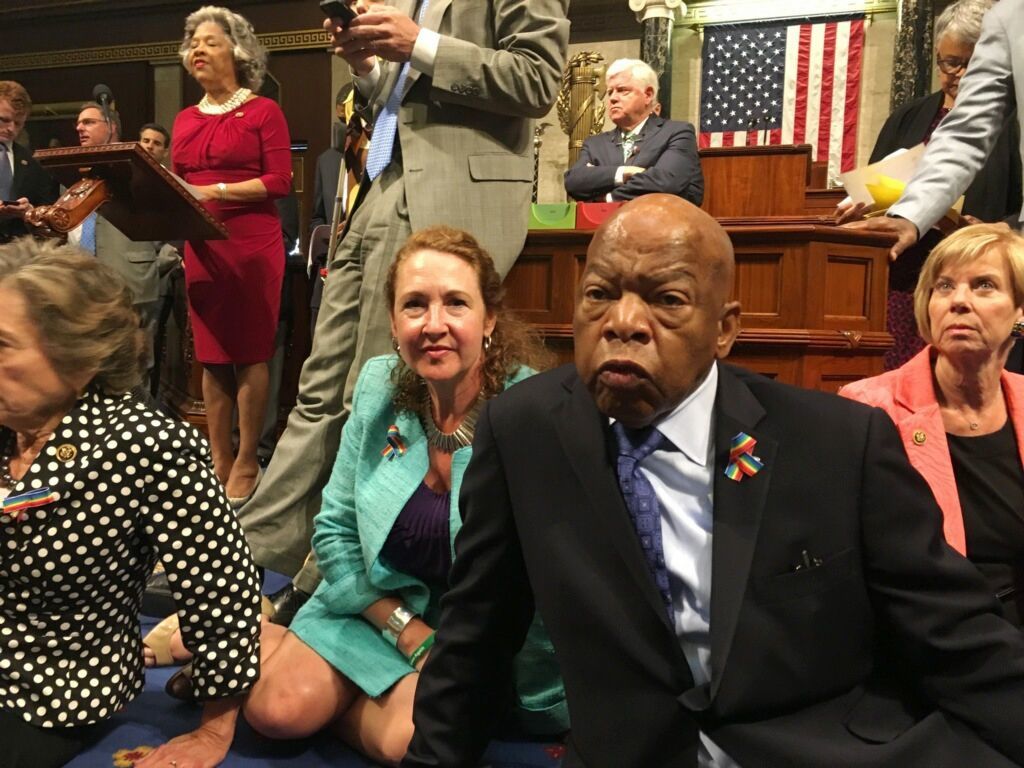

They labeled it a sit-in, and of course, it was memorable enough to see a couple of dozen normally buttoned-down members of Congress assuming awkwardly demure poses after dropping their suited and skirted rear ends to the carpeted floor.

But the element of surprise in that act of collegiate-style civil disobedience soon gave way to something longer-lasting, more consequential, and even more popular among members of the House minority’s rank-and-file.

They had engineered a highly unusual hostile takeover of the House’s proceedings with their “Occupy the Chamber” tactics paralyzing the Republican leadership for hours on end from directing their half of the Capitol with the majority-rules muscle that still normally holds sway.

What the House Democrats were demanding was the same as what their Senate Democratic colleagues achieved last week — a reversal by the GOP bosses to schedule roll call votes before the July 4th recess on expanding background checks and preventing some suspected terrorists from buying firearms.

Although knowing full well that such legislation has almost no chance of enactment, the party has passionately embraced gun control as its newest polarizing campaign issue in the two weeks since the massacre of 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando became the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history.

To get what they wanted, the senators held the floor by staging with textbook precision an old-fashioned “talking filibuster” to prevent any other business by the Senate.

The House members tossed the word “filibuster” around with zeal in describing their behavior, but in almost every practical and parliamentary way, their unorthodox incursion was something else entirely.

For starters, a filibuster is a guaranteed “live continuous coverage” on cable television because it’s insinuated into a formal session of the Senate. But a central aspect of the House’s rump session was how, after a couple of balky efforts to persuade the Democrats to leave the well, the exasperated and outmaneuvered GOP leadership chose to recess Wednesday’s legislative session indefinitely.

And that meant the bulky broadcasting equipment in the chamber — which C-SPAN relies on but is under the control of Speaker Paul D. Ryan — got switched off as a matter of normal procedure.

And that is how the House Democrats ended up staging the first floor protest that more people saw on social media than on TV. Democrats posted a steady sequence of still photographs on Instagram, in violation of the House rules against the use of still or video cameras on the floor, by members or anyone else, whether a session is underway or not.

Even more provocatively, at least four lawmakers took it on themselves to offer a 21st century form of “pool TV coverage” by using the Persicope live-streaming video app on their smartphones to broadcast the goings-on inside the room.

The House rules also say the sergeant-at-arms may restore order to the chamber at the direction of the speaker, which theoretically means the person in charge of the House has the power to bring in his own law enforcement team to quell dissenting voices at any time.

That was clearly an approach Ryan decided against taking. His politically astute preference was a restrained exercise of “soft power” that allowed the Democrats to talk themselves hoarse, even if that took all night and beyond. The far riskier alternative was to engineer a provocation that could transform a benign legislative group therapy session into a rough-and-tumble partisan confrontation of mythical propositions.

Early in the day, the most prominent sit-in participant was John Lewis of Georgia, and surely the GOP top brass gave no serious consideration to forcefully removing from the House floor one of the civil rights movement’s most famous victims of excessive police violence.

But more than 100 lawmakers had taken part in the protest as the afternoon turned into evening, with most House members (including everyone in the leadership) delivering relatively short speeches interspersed by cameo appearances from a lengthening roster of prominent senators.

The image-making risks connected to breaking up the marathon publicity stunt while Nancy Pelosi, Harry Reid or Bernie Sanders was in the room — let alone such potential Clinton vice-presidential choices from the Senate as Elizabeth Warren or Tim Kaine — seemed almost as politically untenable.

The protest was not without some precedent — shared by both parties — and perhaps predictably the last such comparable House event was the summer before the last election for an open seat in the Oval Office.

In August 2008, when the Democrats were in charge and Pelosi was speaker, she gaveled the House into recess for the summer and turned off the TV cameras without granting the minority Republicans a vote on their top messaging bill for the campaign season ahead — to reverse a ban on new offshore oil drilling.

Two-dozen GOP members stayed on the floor demonstrating for more than five hours, even after the chamber’s lights got turned off, and other Republicans flew back to Washington during the recess and took over the unattended chamber for bouts of protest speechmaking. (The publicity, at a time before social media but amidst surging gasoline prices, helped force the Democrats to acquiesce in lifting the moratorium later that fall.)

In November 1995, in the middle of a partial government shutdown engineered by a GOP majority, about 30 Democrats stormed back onto the floor one night after the Republican leadership declared the underlying budget impasse was intractable and a recess was the only logical move.

The melodramatic highlight (not seen on TV) was when some of them paraded through the room with poster-sized renditions of a New York Daily News cartoon portraying Speaker Newt Gingrich as a “cry baby” in a diaper. The protesters threatened to stay all night but ended up departing after a couple of hours. And Congress cleared a temporary spending bill the next day.

The granddaddy of all protests in the House, however, may go to the dramatically outgunned Republicans just a month before the 1968 election. In parliamentary double-bank-shot that, boiled to its essence, was about trying to help Richard Nixon win the presidency, the GOP tried to block passage of a bill that would have effectively forced him into the sort of nationally televised debate he dreaded.

Their last ditch move was to insist on 33 consecutive quorum calls (in the days before electronic voting) over two long days. The only way they were stopped was when Speaker John McCormack did the opposite of what Ryan did on Wednesday — he used his authority under the rules to order the House chamber locked with the members inside until a compromise was struck.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.