The Boeing Co. is turning 100 on July 15. Throughout the year, The Daily Herald is covering the people, airplanes and moments that define The Boeing Century. More about this series

War is in Boeing’s bones.

As it turns 100, Boeing is best known for making big commercial jets that have carried billions of travelers around the globe. For much of its history, though, Boeing has depended on military orders for business.

William Boeing and Conrad Westervelt, a U.S. Navy officer, started the company to make military airplanes. At the time, World War I was raging, spurring the rise of military aviation.

The idea of flying paying passengers was then more theory than practice. The first passenger airline had briefly operated a couple years earlier. The St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line offered rides across Tampa Bay for $5 one way (about $119 in 2016).

After World War I, demand for warplanes dried up. To keep the lights on, the Boeing Co. had to make furniture along with airplanes. In the 1930s and 1940s, the company found success making bombers and other big military planes. Boeing was not the biggest airplane maker during World War II, but it won several key contracts after the war — for the B-47, the B-52 and the KC-135. Since then, most — but by no means all — of Boeing’s successes have come from commercial jetliners.

Here are some of the most significant Boeing military products. This list does not include planes that Boeing took over through mergers and acquisitions.

Model C: Boeing’s first warplane

Boeing designed the Model C seaplane as a trainer for the U.S. Navy after the United States entered World War I.

The plane marked several firsts for the young company: first all-Boeing design, first production order and first profitable airplane program. It was designed by Wong Tsu, Boeing’s first aeronautical engineer. The company built 56 Model Cs, most for the Navy. Bill Boeing and test pilot Eddie Hubbard used a Model C on March 3, 1919, to make the first international airmail delivery — a run from Seattle to Vancouver, British Columbia.

Thomas-Morse MB-3A: Stealing success

When airplane orders plummeted after World War I, the Thomas-Morse MB-3A helped Boeing stay afloat during difficult times. For several years, Boeing made furniture and small boats in addition to airplanes to pay the bills.

In 1921, the U.S. Army Air Service solicited bids to build 200 MB-3As. With access to cheap spruce and more efficient production systems, Boeing underbid the plane’s designer, Thomas-Morse Aircraft in upstate New York, for the contract.

While the deal buoyed Boeing, it was a serious blow to Thomas-Morse. It wasn’t able to absorb the plane’s development costs and was taken over by Consolidated Aircraft a few years later.

PW-9/FB: Boeing’s first fighter

In World War I, the U.S. military relied on French- and British-designed fighters and bombers. By the early 1920s, Boeing and other American airplane makers were catching up.

Boeing engineers used what they had learned from the MB-3A in designing what the company named the Model 15. It was the first Boeing-designed fighter plane.

The Army and Navy both ordered the biplane in 1923. The Army Air Service designated it PW-9, which stood for “pursuit water-cooled design 9.” It had several designations for the Navy — FB-1 through FB-5. Boeing delivered 157 of the fighters, as well as 77 trainer derivatives, called NBs by the Navy.

Its performance established Boeing’s reputation as a warplane producer, and its steel frame marked Boeing’s move away from spruce-and-wire airplanes.

Y-1B/B-9: The Death Angel

The B-9 bomber broke with the cumbersome-looking biplane bombers of the day.

Its streamlined fuselage and single wing gave it a sleek look and enabled it to outrun fighters. It also had four machine guns to fend off any fighter that got close.

A 1931 article in Modern Mechanics dubbed the plane the Death Angel, and described it as a “veritable flying fortress.” That moniker would be more famously applied to Boeing’s next bomber design.

Few Death Angels were produced. The B-9 was soon surpassed by the Glenn L. Martin Co.’s B-10 bomber.

Boeing’s first swept-wing jet bomber, the B-47, flew less than 20 years later.

P-26: Peashooter

By the late 1920s, Boeing had produced several successful biplane fighters, including the P-12/F4B. The plane — called P-12 by the Army and F4B by the Navy — first flew in 1928, and Boeing delivered nearly 600 within four years.

Despite the plane’s success, Boeing engineers were already exploring a monoplane fighter when the P-12/F4B first flew.

Their work produced the P-26, a streamlined, open-cockpit fighter popular with pilots. The plane was among the fastest of its day. But by the time the United States entered World War II, the P-26 had been surpassed by more modern planes and had been all but taken out of front-line service. A few remained in service with Filipino units.

When Japan attacked the Philippines, the Japanese devastated Filipino and American air units. However, on Dec. 12, 1941, Capt. Jesus Villamor led the 6th Pursuit Squadron of the Philippines Army Air Corps against a fleet of enemy bombers escorted by agile Zero fighters. Despite being outclassed by the Zeros, Villamor downed two. However, a few days later, his unit destroyed its planes rather than let them be captured.

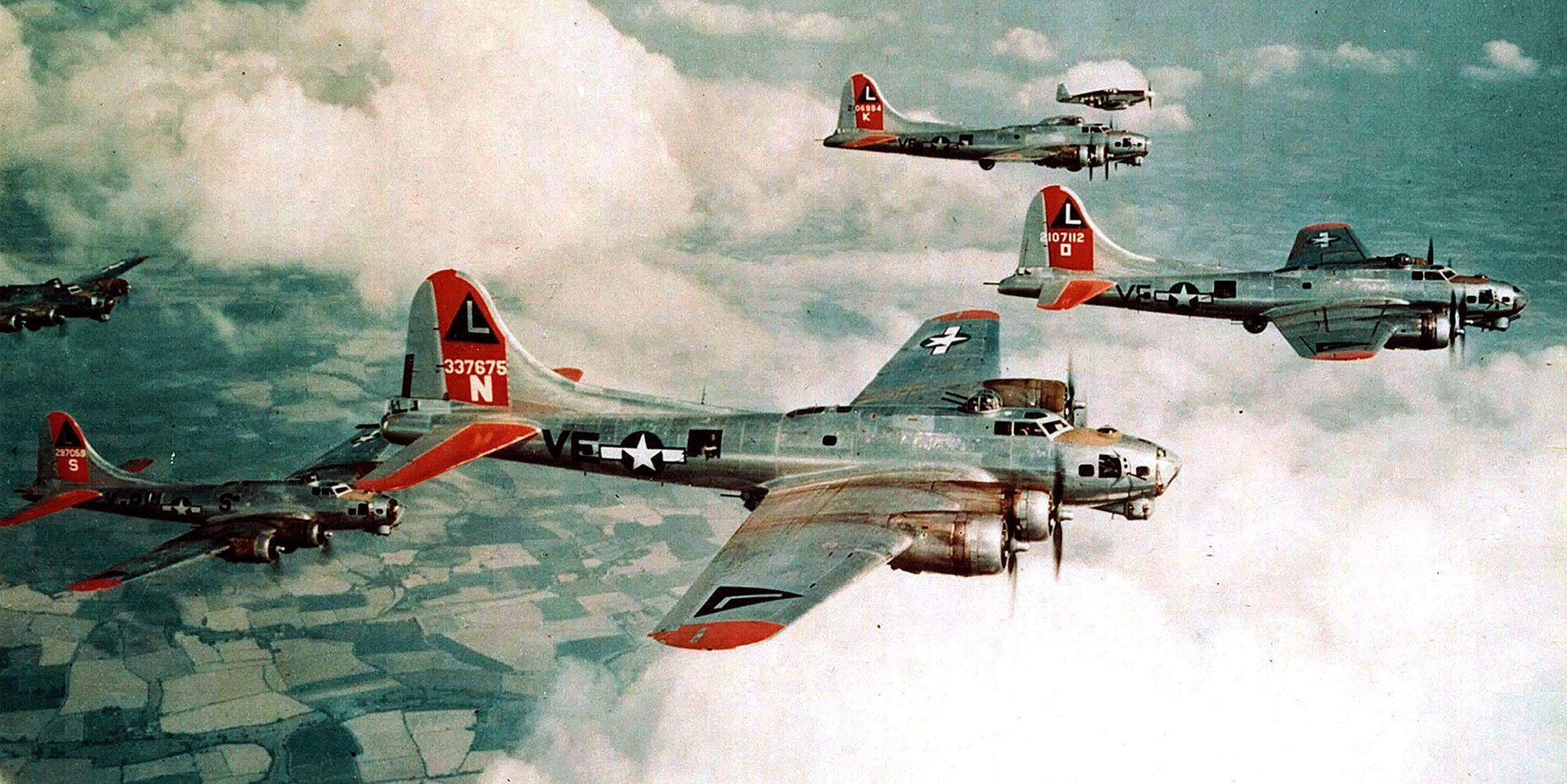

B-17: Built to fight

When the U.S. Army asked American airplane makers to develop a long-distance, heavy bomber, Boeing was losing money and cutting jobs. Its Model 247, the first modern airliner, took flight in 1933 but wasn’t selling. There were few profitable prospects. So the company’s board backed chief engineer Claire Egtvedt’s vision of a powerful four-engine warplane, essentially betting the company to bankroll development costs. Boeing engineers delivered.

Part racehorse, part draft horse, the Model 299 could haul more bombs than other bombers and outrun any fighter of its day. The Army Air Corps dubbed it the B-17.

When the plan first rolled out in 1935, a young Seattle newspaperman, Richard Williams, was tasked with composing a photo caption. He wrote, “Declared to be the largest land plane ever built in America, this 15-ton flying fortress, built by the Boeing Aircraft Co. under Army specifications, today was ready to test its wings.” The flying fortress moniker stuck. Boeing quickly noted its PR value and trademarked the term.

The prototype crashed during a test flight, killing Boeing test pilot Leslie “Cowboy” Tower and Major Pete Hill. The Army picked the Douglas B-18, but ordered a handful of B-17s, too. Within a few years, the B-18 was obsolete, while the B-17 was still ready for the front lines.

Boeing designed the B-17 to be durable and ferocious. The idea was for a bomber able to shoot down attacking planes and remain aloft despite damage it suffered.

In 1944, Arlington resident Art Unruh was a 20-year-old staff sergeant and waist gunner on a B-17 in the 15th Air Force’s 32nd Bombardment Squadron. His plane hit some of the most heavily defended targets in Europe.

“We were so busy in the air, there was no time to be scared,” Unruh told The Daily Herald in Everett in 2015. “It’s when you get back and start walking around that airplane — it’s butchered and beat up. You get shaky.”

On his last mission of the war, his plane limped home with much of its vertical fin blown away and more than 600 holes from flak and bullets fired by enemy fighters.

Col. Robert Morgan, pilot of the most famous B-17, the Memphis Belle, told an interviewer, “We could never have flown the B-29 in Europe. It wouldn’t have taken the punishment. Ö The B-17 was built to fight and that’s what it did, it fought.”

The butcher’s bill for B-17 crews could be terrible. On Oct. 14, 1943, 291 Forts took off from England to bomb factories in Germany; 60 planes, more than one in five, did not return.

Despite the losses, America’s airplane industry turned out bombers faster than the Axis air forces could shoot them down. In March 1944, Boeing’s Seattle plant alone built 362 B-17s. In all, more than 12,000 B-17s were made by Boeing and other manufacturers working under license.

B-29: Rushed into combat

The B-29 Superfortress was the most sophisticated bomber of its day. It could fly higher, faster and farther with more bombs than any other plane. During World War II, the B-29s and their crews took the fight to Japan. Flying from distant bases, they attacked the country’s ability to wage war. In August 1945, two B-29s dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan surrendered a few days later.

The B-29 bristled with computer-controlled machine guns. It had pressurized crew cabins, allowing it to fly higher than other bombers.

Boeing built a new plant in Wichita, Kansas, to handle most of the final assembly work. But problems dogged the program early on, delaying deliveries. Hundreds of military and civilian mechanics descended on the plant, working outside, sometimes through snowstorms. Subcontractors stopped all other work. Within a few months, Boeing and the Army Air Forces had won the Battle of Kansas.

While the production issues were worked out, the Superforts suffered technical problems when first introduced in 1943, especially engine fires.

“Scared? If you weren’t, you weren’t normal,” Everett native Harry Spencer told The Daily Herald in 2014. He flew 35 combat missions as a bombardier and second lieutenant. Those sorties included the B-29’s first combat mission and the bomber’s first raid over Japan.

American forces switched tactics to begin firebombing Japanese cities. Spencer recalled flying over Tokyo: “It looked like the whole city was ablaze — the fires, the ack ack, planes going down — ours and theirs. It was just like flying into hell.”

C-97 Stratofreighter

American industry ballooned rapidly during World War II. The downsizing after the war happened just as fast, and it hit workers and companies hard.

Many expected a post-war boom in commercial air travel, which never materialized. Boeing sold few 377 Stratoliners, but it sold 888 of its military variant — the C-97 Stratofreighter. Most were KC-97s, the U.S. military’s first dedicated aerial refueling tanker.

B-47: Setting the standard

In the summer of 1945, a 32-year-old Boeing engineer was taken to a collection of nondescript, low-rise buildings in the woods of western Germany. What George Schairer found there changed American aviation and the Boeing Co.’s future.

He dashed off a letter to Seattle: “The Germans have been doing extensive work on high speed aerodynamics. This has led to one very important discovery.” Then he drew a wing sweeping back. The angled swept wing was a critical breakthrough necessary to get the most out of jet engines.

The discovery, combined with two years of Boeing’s own research and development, led to the B-47 Stratojet.

As the post-war elation chilled into the Cold War, B-47s stood ready to take nuclear war to the Soviet Union. The bomber was retired in the mid-1960s, but its shape and configuration set the standard for big jet airplanes to this day.

B-52: Stratofortress

Every Air Force pilot flying a B-52 Stratofortress is younger than the bomber they’re flying — usually by several decades. Boeing started making B-52s in 1952, yet the workhorse refuses to retire. It has outlasted several replacements — and even its replacements’ replacements.

Its durability is a testament to its ruggedness and flexibility — and to how little aviation technology has progressed since the ’50s. The 76 B-52s that make up the Air Force’s long-range punch are getting an upgrade to bring them into the digital age. However, their bones are still of 1950s vintage.

During more than 60 years in active service, B-52s have dropped everything from leaflets to a nuclear bomb. After the Soviet Union fell, the United States cut the wings off 365 B-52s as part of post-Cold War disarmament. However, the Stratofortress is still flying. It is expected to stay in service until at least 2040.

KC-135: Flying Gas Station

In 1954, Boeing test pilot Tex Johnston famously rolled the company’s Model 367-80 while flying over Lake Washington. The company built the plane to prove the concept of jet transport, and it delivered. It led to the KC-135 Stratotanker and its sibling, the 707. Boeing made more than 800 KC-135s and variants. They continue to be the Air Force’s primary aerial refueling tanker — at least for now. Boeing is making a replacement, the KC-46 Pegasus.

Minuteman missile: Always ready to defend

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched a small satellite — Sputnik — that passed silently overhead, inspiring awe and fear in America. If the USSR could launch a satellite, it could soon launch a nuclear missile capable of leveling U.S. cities.

In response, Boeing developed the LGM-30 Minuteman missile. It was named after the Revolutionary War militiamen ready to pick up their muskets at a minute’s notice. During peak production, the program employed nearly 40,000, mostly in Seattle and at a final assembly site in Ogden, Utah.

By the 1970s, 1,000 missiles were deployed at launch sites around the U.S. Today, 450 missiles are still active. The Air Force plans to keep the Minuteman in service until at least 2030.

CH-47 Chinook: Twin-rotor workhorse

Designed in the early 1960s, the CH-47 Chinook is one of a handful of aircraft from that time still in production. Boeing has produced more than 1,200 of the twin-rotor helicopters. At peak production in 1967, the Boeing Vertol plant in Philadelphia rolled out a new Chinook every 24 hours.

V-22: Controversy takes flight

What takes off like a helicopter, flies like an airplane, and saw its development costs balloon by 1,000 percent? The Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey was one of the most controversial weapons programs in recent decades.

Bell Helicopters and Boeing started developing the tiltrotor aircraft in the early 1980s. The V-22 did not enter active service until 2007. The innovative aircraft’s engines and rotors point up, allowing for vertical takeoffs and landings. Once in the air, they tilt forward and the V-22 flies like an airplane.

Critics say that it is expensive — about a $100 million sticker price — to buy and fly, and it does not perform as well as the CH-47 Chinooks and CH-46 Sea Knights it is meant to replace. The Pentagon’s former top weapons tester told the New York Times that the V-22 is like a bad poker hand — and the Marines keep betting on it.

The Marine Corps and other Osprey supporters say it outperforms traditional helicopters — especially as a medevacs — and its capabilities justify the price tag. They also say it is as safe as any other military aircraft. How-?ever, a 2015 crash that killed two Marines renewed safety concerns.

F-22: A Flying Fortune

Boeing got back into the fighter business in the 1990s when it teamed with Lockheed Martin to design and build the F-22 Raptor, a stealth, fifth-generation fighter. Like nearly every modern weapons program, the fighter has not performed quite up to what was promised. The F-22 generally has done well (and certainly better than its successor, the Lockheed Martin F-35).

Even so, the Pentagon stopped F-22 production in 2011 after 187 deliveries. But Boeing will likely still be making jet fighters into the next decade. When the company bought McDonnell Douglas in 1997, it inherited the F-18 Hornet, which is assembled in St. Louis. Boeing has upgraded and enhanced the durable 1970s-vintage warplane. While not as fancy as an F-22 or an F-35, the F-18 and its variants have done something neither of those 21st-century jets can claim: They’ve proven they can get the job done without a lot of fuss and drama — and for a lot less money.

P-8: Submarine hunter

The P-8 Poseidon is the U.S. Navy’s new submarine and ship hunter. Based on Boeing’s 737-800, it is assembled in Renton. The P-8 entered service in late 2013.

KC-46: Fueling distant fights

After a messy bidding process that included a couple do-overs, Boeing won the Air Force’s contract to develop a new aerial refueling tanker based on its 767. The KC-46A is assembled in Everett, and is in development. It is slated to enter service in 2017, when it will start replacing 1950s-era KC-135s.

With its long range and large fuel capacity, the Pegasus, as the KC-46 is called, is critical to extending American air power to far-flung hot spots.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.