EVERETT — The stories keep trickling in across the county.

Each shares a common thread: police officers and sheriff’s deputies equipped with a nasal spray antidote bringing people back from death’s doorstep.

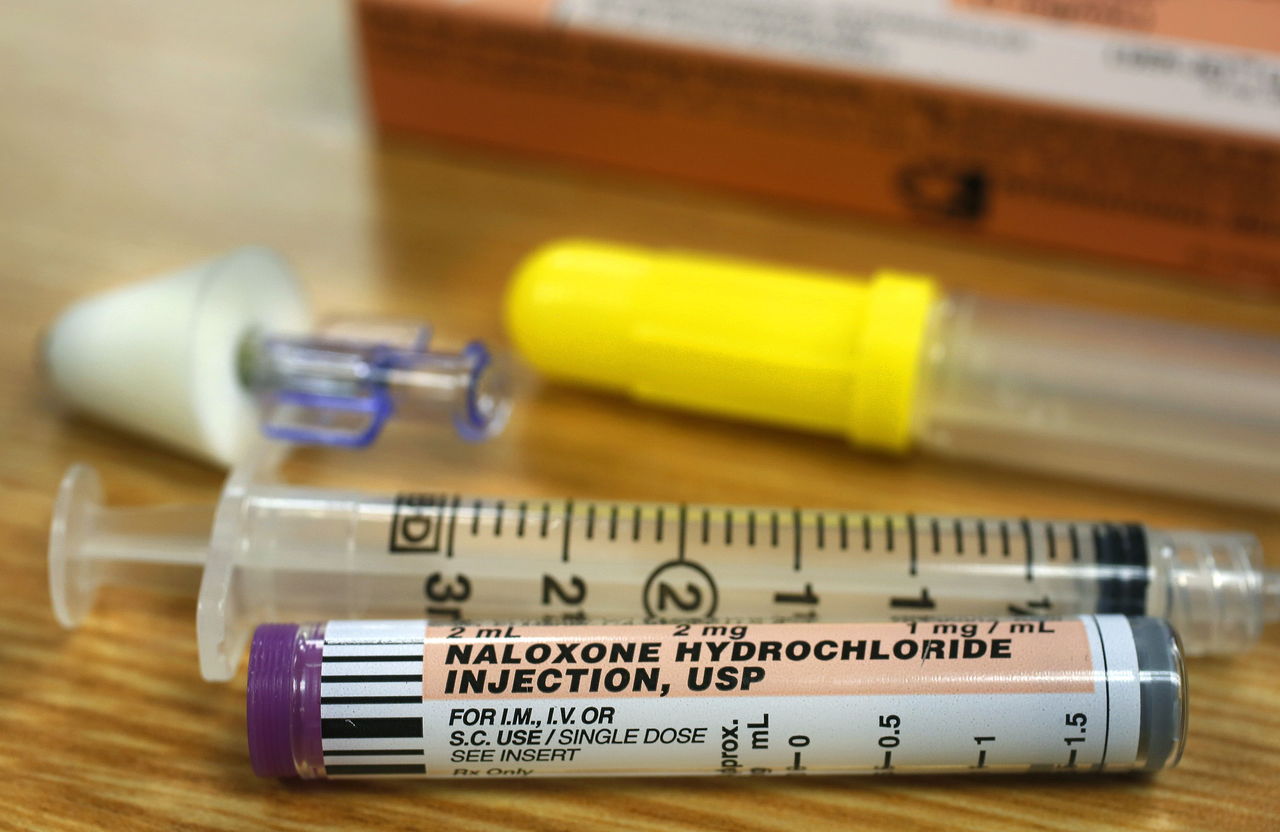

They’re dispensing naloxone, better known as Narcan, a prescription medication used on people who have overdosed on heroin or other opioid painkillers, such as morphine, oxycodone and Vicodin.

The success in saving lives has caught the attention of the White House, whose Office of Drug Control Policy early this month recognized Snohomish County for its innovative efforts in preventing overdose deaths.

More than 30 people have been saved since training among several local police agencies began in May.

“By bringing together law enforcement, lifesaving drugs, and social services, we can begin to save lives and give people the chance to heal,” Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers said.

While emergency medical professionals have used naloxone for decades, often through injections, it represents a cultural shift for law enforcement.

“It is not traditional policing but the epidemic isn’t traditional either,” Snohomish County Sheriff Ty Trenary said. “My folks were interested in what we could do to make a difference.”

In 2013, the most recent year complete statistics are available, 580 overdose deaths attributed to opiates were reported in the state. Snohomish County accounted for 86 of them — roughly one in six.

The nasal spray cannot harm the patient and is much simpler to administer. It blocks the effects of opioid overdose, which includes shallow breathing. If administered in time, it can reverse overdose symptoms within a couple of minutes. Each kit costs about $40.

The first reported save was by a Snohomish County Sheriff’s deputy of a Lake Stevens woman in early May, shortly after the deputy had received training and the overdose kit.

On Feb. 17, sheriff’s deputy Kelly Willoth encountered a man, 26, unconscious and slumped over in a Ford Explorer in a supermarket parking lot in Stanwood. The man was in the passenger seat, his head down and he was gasping and drooling. Willoth noticed evidence of heroin use, brought out her naloxone kit and gave him what medics later described a life-saving dose.

On March 7, Lake Stevens police arrived first to a reported overdose in a recreational vehicle. Inside they found a man, 43, giving CPR to his wife. The man told police he’d injected her with heroin because she’d been complaining about a toothache and he thought it would help with the pain. Police administered two doses of Narcan, which brought the woman back to consciousness.

The sheriff’s office focused much of its initial training on deputies working in rural areas who were likely to arrive at overdose scenes before volunteer fire departments.

In Everett, where there have been 21 saves, including six so far this year, every patrol officer is trained in dispensing naloxone. By contrast, in 2014, paramedics with the Everett Fire Department used Narcan on 153 patients, all by needle.

Everett police Lt. Jeraud Irving is passionate about equipping officers with the antidote. As a firefighter and emergency medical technician in the early 1990s, he’d seen how effective naloxone could be.

He also knew that some police officers initially would be reticent.

That perception changed quickly, he said.

“The people who were hesitant to using it are now saying, ‘How can I do more? What more can I do to help,’” he said.

Irving has worked closely with the Everett Fire Department to “make sure we are on the same sheet of music.” Police give way when medics arrive, but the use of naloxone and early CPR improve the chances of survival. He sees police officers playing a supporting role in a community-wide effort to confront addiction.

In an early case, Everett police found an ashen-faced overdose patient who was not breathing. About two minutes later, after receiving Narcan and CPR, the patient began talking and was able to walk to a medic unit.

To Irving, it is not about making personal judgments. With opiate addiction so prevalent these day, he knows many people from different walks of life are affected through family, friends or co-workers.

“You can’t judge a book by its cover and each person has their own story,” he said.

Eric Stevick: 425-339-3446; stevick@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.