By The Herald Editorial Board

With less than a week before the end of the legislative session, negotiators for House and Senate are stitching together an agreement on a supplemental budget that will take advantage of a windfall of $1.3 billion more in additional revenue over the next three years than was earlier expected.

A significant portion will go toward lawmakers’ continued work on better funding for K-12 education, but Democrats, who narrowly control both chambers, also are looking to ease some of the pain from a spike in property tax bills this year caused by last year’s levy swap.

That’s a legitimate use of a portion of that new revenue, but there’s an equally legitimate purpose — three actually — that the state treasurer would like to see receive some of that windfall.

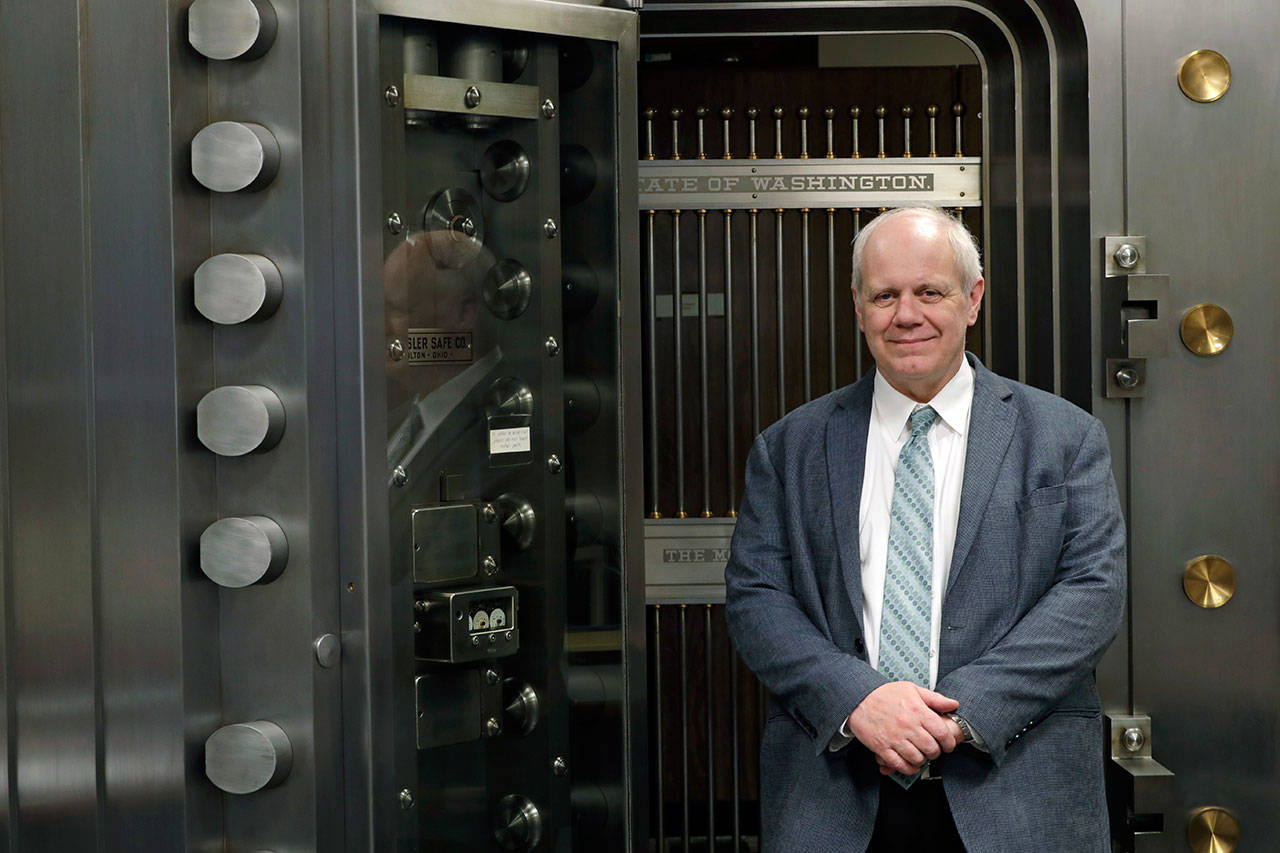

Duane Davidson, now in his second year of office, hasn’t been one to pursue many policy issues with lawmakers, unlike his predecessor who outlined an ambitious tax reform proposal that earned little interest. But Davidson has taken a stand to defend against raids of the “rainy day” fund and asked lawmakers to consider using some of the additional revenue to pay down the state’s bond debt, add to its “rainy day” reserves or pay more toward its unfunded pension obligations. Their choice.

“I think that money would be better spent paying down any debt, pick your debt,” Davidson told the Associated Press last week.

And there’s significant debt to pay down.

The state’s Debt Affordability Study for 2018, released by Davidson’s office, reports that the state’s debt portfolio has over the course of the last 20 years grown from $6.8 billion to more than $19 billion and totals $21 billion when financing contracts are included.

Washington state is among the top — bottom? — ten states in the union for highest state debt as a percentage of personal income and as a percentage of gross state product. And it has the nation’s sixth highest debt per capita. If the state sent a bill to every woman, man and child in the Evergreen State, each would end up paying $2,717 to zero out the debt. The national average for such a bill would be about $1,000; for Nebraska residents, the bill would be zero.

The state hasn’t been irresponsible in what it has spent money on. The largest portion of debt from bonds pays for roads, bridges, transit and other transportation projects, as well as the projects that are funded every other year through the capital budget, including schools, community centers, parks and more.

But the state hasn’t been paying down that debt and instead has added to it, preferring to use its credit card rather than increase taxes — such as a capital gains tax — or make difficult choices on spending.

This fiscal year, the state is schedule to pay about $1.2 billion, about 5.8 percent of its general fund revenues to pay for debt service, in other words, the interest on its debt. That’s the lowest percentage paid, Davidson’s office reports, since 2008, when the figure was 5.3 percent. During most years since 2008, the state has managed to pay between 6 percent and 7 percent.

Even with that debt load, the three credit rating agencies — S&P, Moody’s and Fitch — still give Washington state’s bond credit rating a strong rating of either AA+ or Aa1, largely based on the state’s booming economy, good financial management and relatively well-funded pensions, the treasurer’s office report says.

But that strong economy also points to an ability that isn’t being tapped that could — with relatively little pain at the moment — put more toward paying down that debt.

Admittedly, this late in the session, there’s little chance we’ll see legislators take a cue from Davidson — or for that matter from personal finance maven Michelle Singletary — and begin paying down the debt this year.

But it’s a subject lawmakers should return to next session when the budget process begins again, and before the state actually has send out those bills for $2,717.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.