EVERETT — Heroin killed her son.

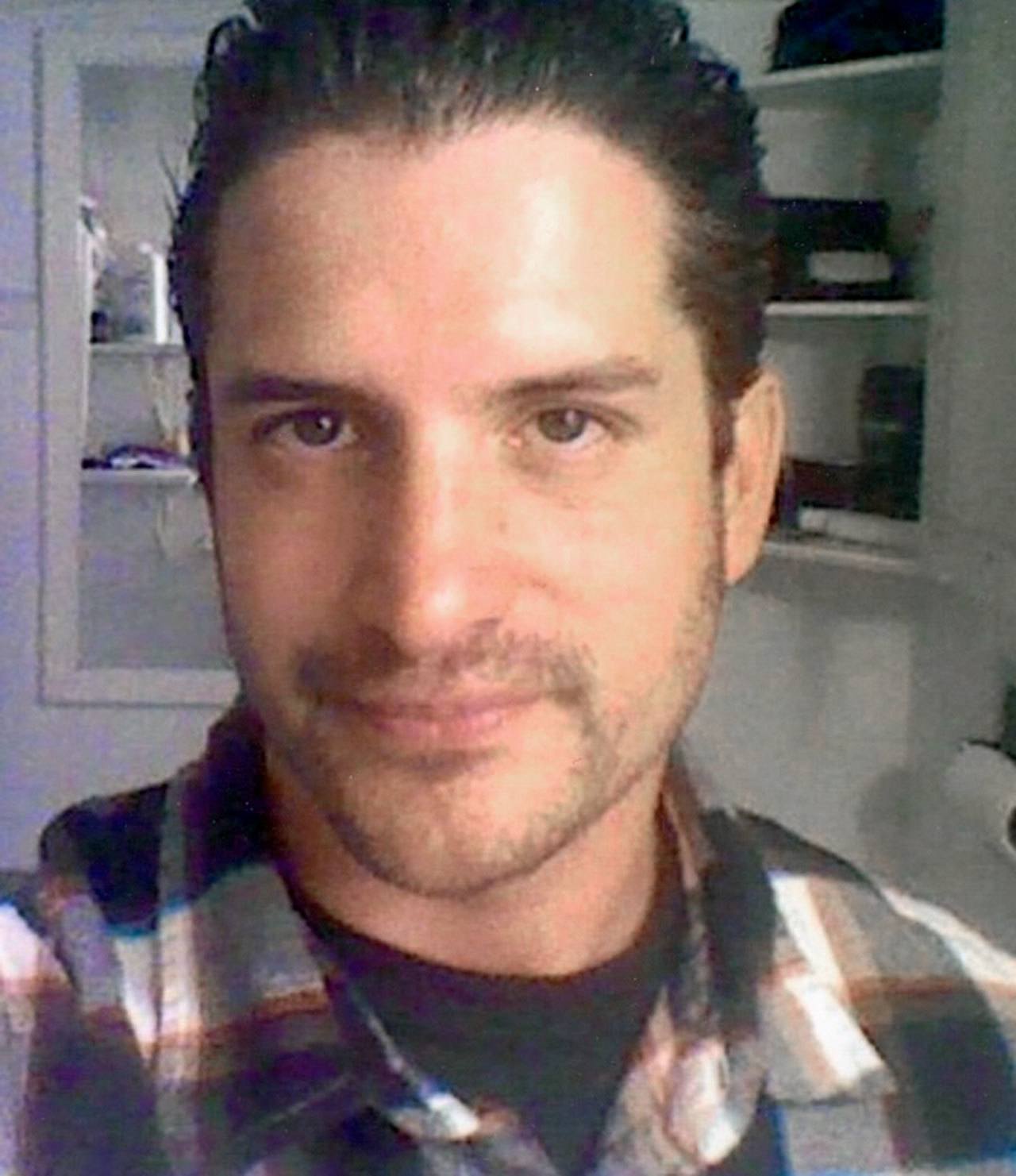

Ian Digre was alone in a borrowed car at the end of a Marysville cul-de-sac. He was wearing his Mr. Electric uniform. There were groceries in the back seat and a soda cup from Taco Bell in the center console. His cellphone on the floorboard was ringing.

A needle rested on the driver’s seat near his legs.

“My son was left to die,” Jude Digre said. “He was left there when someone could have called 911.”

Marysville police don’t believe Ian Digre was alone in the car March 19 when he injected heroin or when he showed signs of distress. They believe a woman, Digre’s friend, was with him and fled without calling for help.

Prosecutors recently charged Gabrielle Waller, 30, with controlled substance homicide in Digre’s overdose death. They allege that Waller sold Digre, 35, the heroin that took his life.

“The Defendant is a risk to the community. The Defendant is a known drug dealer who provided drugs to a supposed good friend and left him to die,” Snohomish County deputy prosecutor Elise Deschenes wrote in charging papers.

Waller missed a court hearing the day before she allegedly sold Digre heroin. She “was more concerned with not being arrested on an outstanding warrant than rendering aid to her ‘friend’ she gave drugs to,” Deschenes added.

Waller, a convicted felon, has pleaded not guilty to the charge. She remains held on $150,000 bail. Waller faces up to five years in prison if convicted.

Controlled substance homicide has been on the books for years, but isn’t often charged because it can be difficult to trace the source of the drugs. Snohomish County deputy prosecutors have pursued cases in the past, however.

A Snohomish County jury convicted a teenager of controlled substance homicide in 2008 in connection with the Ecstasy overdose death of 16-year-old Danielle McCarthy in Edmonds. A Mountlake Terrace man was sentenced in 2011 to eight years in prison for providing the heroin that killed 18-year-old Bridgette Johns.

Marysville police Sgt. Jeff Franzen believes this is the first controlled substance homicide case his department has been able to refer to prosecutors.

“We’ve tried in the past, but we have not been able to get to an arrest,” he said. “Often when we arrive at an (overdose) there’s nobody around, no witnesses.”

In this case, detectives recovered text messages between Digre and Waller setting up the drug deal, according to court documents. A witness also stepped forward to report that Waller admitted that she sold Digre the heroin. She allegedly said she gave him the syringe and tie-off, too.

Waller allegedly told the witness that after Digre injected the heroin he nodded off. “The Defendant said she freaked out and began pouring water on the victim, shaking and slapping him,” Deschenses wrote.

Waller said she thought Digre was OK because he started making noises. She was worried about being arrested because of her warrant, according to court papers. She took Digre’s $20 and left him, police were told.

Digre was discovered the next day by some juveniles who had sneaked off to smoke cigarettes. They told police they believed he was passed out when they first spotted him in the car. Digre was still there a few hours later so they banged on a window. They called 911 when Digre didn’t respond.

A neighbor told police he noticed the car parked there overnight.

Detectives contacted Digre’s girlfriend, who said she hadn’t seen him since the night before he was found. She said they’d argued and Digre drove off, according to court papers.

Police were told that Digre had used heroin and methamphetamine in the past. His family believes he had been drug-free for several months before the night he died.

Dallas Digre said he wonders what derailed his brother’s clean stretch. He is certain his older brother wouldn’t have turned to heroin if he was in a good place.

“It’s not a drug to use to be happy. From my perspective I think he used to self-medicate his own despair,” Dallas Digre said.

Dallas Digre knows firsthand that an addiction can take priority over just about everything else. He has been clean about five years. “Drugs turn you into someone you aren’t or ever thought you’d be,” he said.

Heroin’s potency varies and people’s tolerance to the drug changes. Users can never be certain how much they’re taking or how their bodies will react, according to addiction specialists.

Heroin and other opiates slow the body’s respiratory system and some people simply stop breathing. Police in Snohomish County now carry naloxone, better known as Narcan, a prescription medication to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. There have been dozens of saves by law enforcement officers.

Marysville police are called to a heroin overdose death at least once a month, Franzen said. There’s just no way to know how potent the drug is, he said. In 2014, Marysville police investigated five overdose deaths in a month. Some of the deceased were long-time users. The heroin on the street, they figured, was purer than normal.

“That one time can be their last time,” Franzen said.

Records show that Digre texted Waller, asking to buy $20 worth of heroin. She sent him multiple messages to set up a location and time. When he didn’t answer, she texted him again and again, court papers said.

“I don’t know why he felt the need to respond to her,” Jude Digre said. “She knew he was struggling. It’s a cruel thing to do.”

It’s even harder for the Everett mom to comprehend someone leaving her son alone when he was vulnerable and in need of help. Why didn’t Waller call 911?

“She did nothing to help him,” Jude Digre said. “She didn’t care. I think she needs to be held accountable.”

A 2010 law grants limited immunity to people who call 911 to get help for anyone showing signs of an overdose. Under the statute, people will not be charged with drug possession if police obtained evidence for that charge only because the person called 911. The victim also won’t be charged with drug possession. The law doesn’t offer protection from other criminal charges.

“The moral of the story is don’t be a drug dealer,” Franzen said.

Digre grew up in Marysville with two sisters and two brothers. He had a great sense of humor and was spiritual, Dallas Digre said. He was generous with his time, his mom said. Digre is survived by a 17-year-old daughter.

Jude Digre doesn’t know when her son started using heroin. He was secretive about his drug use. She had hoped this was the time he’d finally overcome his addiction.

“This could have been the year he got better,” she said.

Diana Hefley: 425-339-3463; hefley@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.