By Lori Aratani, Luz Lazo, Michael Laris and Ashley Halsey III / The Washington Post

While authorities in Ethiopia on Thursday described key similarities between the crash of a 737 Max in Addis Ababa and another in Indonesia, important questions about their causes remain unanswered, underscoring how difficult it will be for Boeing to rebuild trust and convince newly emboldened international aviation safety regulators to allow the plane back in the air.

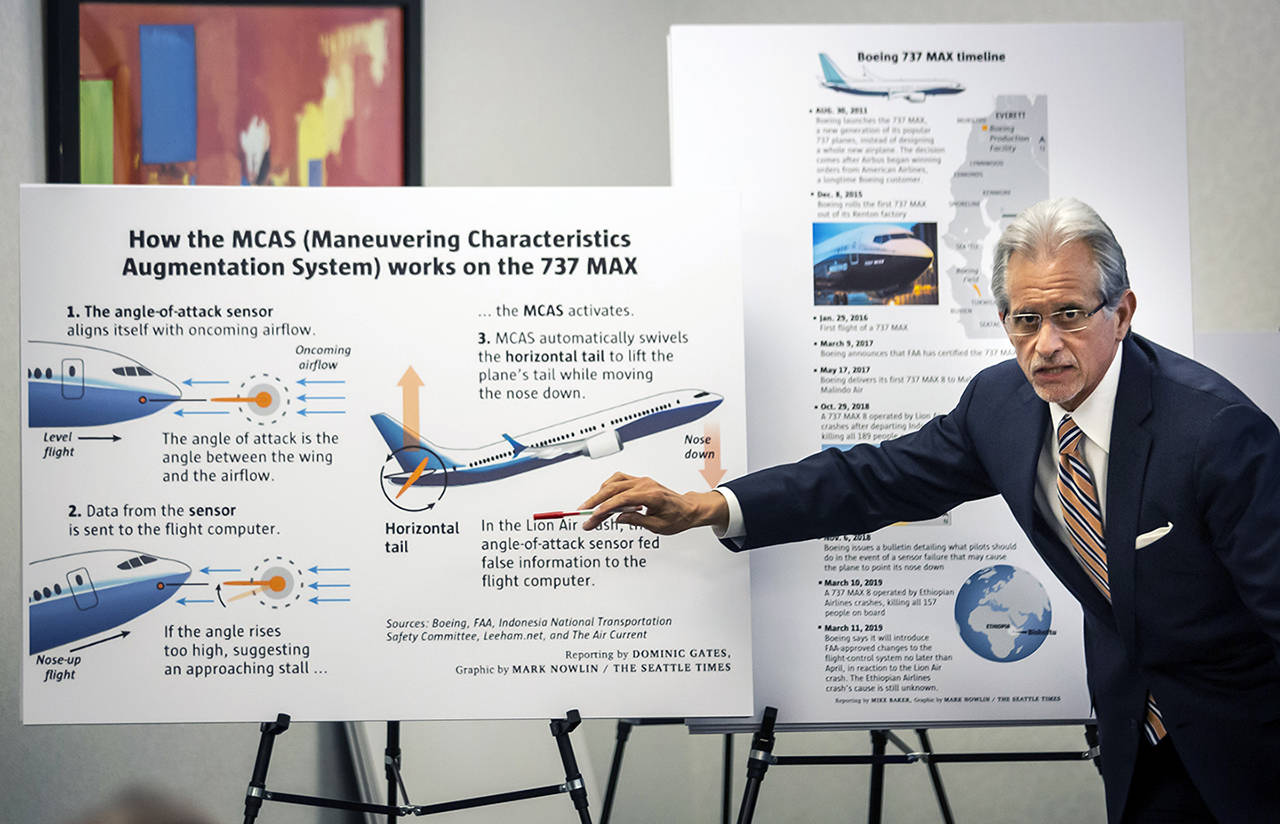

In both crashes, investigators believe an automated anti-stalling feature known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, repeatedly pushed the planes’ noses downward, thwarting pilots who were struggling to regain control.

In a brief summary of investigators’ preliminary findings in Ethiopia, Transport Minister Dagmawit Moges said Thursday that the crew of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 “performed all the procedures, repeatedly, provided by the manufacturer but was not able to control the aircraft.” She cited “repetitive uncommanded aircraft nose-down conditions,” and called on Boeing to review “flight controllability” issues on the plane.

Among the core questions following Moges’ statement is how Ethiopian authorities on the one hand, and Boeing executives and the Federal Aviation Administration on the other, could have presented such starkly different pictures of how pilots can handle such issues with the 737 MAX.

Mike Sinnett, Boeing’s vice president of product strategy and development, said last week that “pilots can always electrically or manually override the automatic system.”

The FAA, in an emergency order nine days after the Indonesia crash, said bad data from an external “angle-of-attack” sensor could lead to “difficulty controlling the airplane” and “possible impact with terrain.” But the FAA said pilots could “disengage autopilot” and use other controls and adjust other switches to fly the plane in such a case.

Moges is essentially saying those procedures didn’t work. But why?

Boeing said it will examine the preliminary report. In a statement, the FAA said: “We continue to work towards a full understanding of all aspects of this accident. As we learn more about the accident and findings become available, we will take appropriate action.”

Aviation experts also pointed to a host of additional ongoing questions about what led to the dual disasters that killed 346 people in less than five months.

Among them: What was the precise sequence of failures – technological and human — that were at play?

Experts said erroneous information from the “angle-of-attack” sensors — which measure the difference between the nose’s direction and the angle of the oncoming wind — triggered the automated MCAS feature that investigators believe was a factor in the disasters.

But how did such crucial data become flawed in the first place, given that Boeing says it has tens of millions of hours of previous experience with the sensors, which it considers highly reliable?

Amdeye Ayalew, who is heading the Ethiopian investigation, said the sensor was neither damaged by a foreign object nor affected by a “structural design problem.”

And there has been no information released publicly about other mechanical problems with the plane in Ethiopia, experts said.

“Lion Air had mechanical problems for days before the accident. Ethiopian did not. So there’s two completely different paths to get the erroneous data started,” said John Cox, a former pilot and an airline-safety consultant who has been privately briefed on the evidence in Ethiopia by people familiar with the investigation. “Once the data became erroneous, then you have very similar accidents. But you have very different accidents up to there.”

A spokesman for the FAA declined to say what the agency has learned about the source of the erroneous data in the crashes. “We continue to support the NTSB on both ongoing investigations,” the spokesman said, referring to the National Transportation Safety Board, adding the that FAA is prohibited from providing more information.

Shem Malmquist, a Boeing 777 captain and a visiting professor at the Florida Institute of Technology, said a possible explanation for the bad data may be a malfunction in a device that filters critical flight data from the angle of attack sensors and other inputs and sends it to the pilots’ cockpit displays. Those devices are known as air data inertial reference units.

Similar problems on Boeing, Airbus and other planes were “triggered by a bad processing algorithm, or even just a momentary data spike,” he said.

He thinks a problem with the sensor itself is less likely.

“I know of only a couple of events directly related to the angle of attack vanes themselves. One of those involved frozen vanes due to water getting into them during some unusual circumstances,” Malmquist said.

Boeing has previously said it does not plan to make changes in the angle-of attack sensors it uses on several models of its planes, the 737 MAX among them.

Instead, Boeing last week detailed a software update, in the works for months, that will change the way the data from the sensors is processed. Once the fixes are made, the MCAS feature will use data from both sensors, rather than just one — and if there’s a disagreement of more than a certain amount between the two, that automated feature won’t be used for the remainder of the flight.

Boeing said the software fixes will also include new limits on how often MCAS activates and how strongly it seeks to correct the plane’s flight path once it does. The feature was supposed to increase safety by preventing stalling, since the 737 MAX’s designers had shifted the position of the plane’s engines as part of an effort to save fuel and compete with Airbus.

But in a sign of the technological complexity of the fixes; potential new insights from ongoing investigations; and the realities of dealing with a regulators around the world, who led the United States in the decision to ground the planes, Boeing has now delayed sending its package of fixes to the FAA for certification. The company now says it will do so “in the coming weeks.”

Boeing had indicated just last week that its submission to the FAA was imminent, and the specific cause of the delay remains unclear.

On Wednesday the company released a statement saying Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg had joined Boeing test pilots aboard a 737 MAX 7 flight for a demonstration of the updated MCAS software.

The statement said the flight crew performed different scenarios that tried various aspects of the software changes to test failure conditions.

“The software update worked as designed, and the pilots landed safely at Boeing Field,” the statement said. “Boeing will conduct additional test and demo flights as we continue to work to demonstrate that we have identified and appropriately addressed all certification requirements.”

Civil aviation authorities around the world were among the first to ground the planes, and analysts said they will play a bigger role than before in decisions about returning them to the skies. Some say the FAA’s decision as the last of the major aviation safety authorities to ground the jets — along with its close ties to Boeing — may have cost it some credibility among its counterparts around the world.

Some U.S. officials also said they do not want the planes to resume flying until an independent third-party analyzed the changes.

Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, and Rep. Rick Larsen, D-Wash. said they want the FAA to bring in third-party experts to examine “any recommended technical modifications and any proposed new training requirements for pilots,” which would cover the changes connected with the MCAS feature.

To address those shared concerns, the FAA announced the formation of a technical review team to review the system. The team, chaired by former NTSB chairman Christopher Hart, will include representatives from the FAA, NASA and international aviation authorities. The FAA did not clarify which countries have been invited to join.

“Now it is not just up to FAA to certify and say, ‘It’s good,’” Malmquist said. “All of these different agencies around the world are now saying, ‘No, we really need to have this validated,’ and that is going to be a very interesting problem that I don’t think we have seen before.”

“China, the United Kingdom, Australia — all of them are going to be closely scrutinizing and needing to look at the changes and what’s being proposed, and everyone has to agree to it or you are going to have sections of the world where the airplane won’t be allowed to fly,” Malmquist said.

Officials in Canada said they will not lift flight restrictions on the 737 MAX until they are “fully satisfied that all concerns have been addressed by the manufacturer and the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration and adequate flight crew procedures and training are in place.”

In Australia, officials say they will conduct a thorough review, adding that it is still too early to know when the ban will be lifted. “Given there is not yet any formal advice from the Ethiopian accident investigation it is too early to make judgments on when and how the aircraft type can safely reenter service,” said Peter Gibson, a spokesman for Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA).

At issue in the crashes are questions about the soundness of Boeing’s original design of the MCAS system, and why the company didn’t originally require training for pilots on how it works. It also renews questions about assurances offered by Boeing and the FAA that the planes were safe.

Cox, formerly the top safety official for the Air Line Pilots Association, pointed to differences in the run-up to the two crashes.

The Ethiopian Airlines flight “had flown to Johannesburg and back without any maintenance issues,” Cox said.

By comparison, the Lion Air 737 MAZ had multiple failures starting Oct. 26, including during the four flights before the one that crashed on Oct. 29, according to the preliminary report on the crash. The plane’s maintenance log indicated that pilots reported problems with the speed and altitude displays and that mechanics were brought in to do troubleshooting.

Ultimately, investigators want to understand how much of the crash was due to the airplane itself and whether pilots might somehow have found a way to avoid disaster.

Boeing’s proposed changes also will include additional pilot training and updates to flight manuals.

Even as investigators examine the factors that contributed to the two crashes, the FAA continues to face accusations that it was too slow the ground the planes. There are also questions about the FAA’s relationship with Boeing and the process used to certify the plane was safe.

The Justice Department’s criminal division has launched a probe into the plane, and the Transportation Department’s inspector general is investigating the certification process, among other things.

On Monday, the House transportation committee, which is conducting its own investigation, sent letters to both the FAA and Boeing requesting records related to the certification of the 737 MAX. The committee has created a “whistleblower webpage” and is encouraging current and former officials and employees of the FAA and Boeing who have information they believe might be useful to the investigation to share it anonymously.

The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation this week launched an investigation based on information from whistleblower accounts. They are looking into “any potential connection between inadequate training and certification of Aviation Safety Inspectors who may have participated in the evaluation of the Boeing 737 Max,” the committee said.

In testimony before a Senate subcommittee last week, Acting FAA Administrator Daniel Elwell explained that Boeing’s goal in the redesign of the 737 Max was to make the plane fly exactly as previous generations of the plane had, despite the fact that the engines were somewhat larger and repositioned farther forward on the wings.

To combat the additional lift provided by the new engines, Boeing introduced MCAS, which was designed to push the plane’s nose down to combat that added lift, and to prevent a “stall” that could cause the plane to crash.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.