EVERETT — They’re better known by another name, but to keep this clean we’ll call them “shoddy” robots.

Imagine a Rube Goldberg machine that uses a microprocessor or a drone — instead of two-by fours and marbles— to hold an umbrella over your head or brush your teeth.

The more absurd the better. Examples can be viewed on YouTube or on a subreddit we can’t name.

Students at Washington State University’s Everett campus recently took part in the first “Sh*tty Robot Hackathon,” a 24-hour challenge that drew nearly 30 students.

“The goal is to design a robot that does whatever it’s meant to do — well,” said Anna Boll, a mechanical engineering student at WSU Everett who helped stage the event at TheLab@everett, a business incubator.

Crappy, shoddy, sh*tty robot hack-a-thons — whatever term you favor — pit students against random tech components and a stopwatch.

The results are usually irreverent, good for a laugh and mostly useless.

Or could they contribute to the next quantum leap?

“I don’t know of any cases where a badly built robot generated a breakthrough or novel idea, but I’d probably put money on it happening somewhere,” said Aaron Crandall, a professor in the School of Engineering and Computer Science at WSU in Pullman.

Hack-a-thons can pique student interest in STEM without being stuffy or staid, said Crandall.

“I’m here because I thought it would be fun,” said Carlos Rosas, an electrical engineering student at WSU Everett and an intern at OceanGate, an Everett firm that builds and charters manned submersibles.

“People don’t think of engineers as creative, but we are,” said Rosas, who joined other engineers at the robot-building marathon.

Hack-a-thons give students the chance to demonstrate their classroom skills and can even help land them a job, said Crandall. (Hey, I built a voice-activated robot that flings confetti and lights a candle!)

The contest started at 10 a.m. on a Saturday and ended at 10 a.m. Sunday.

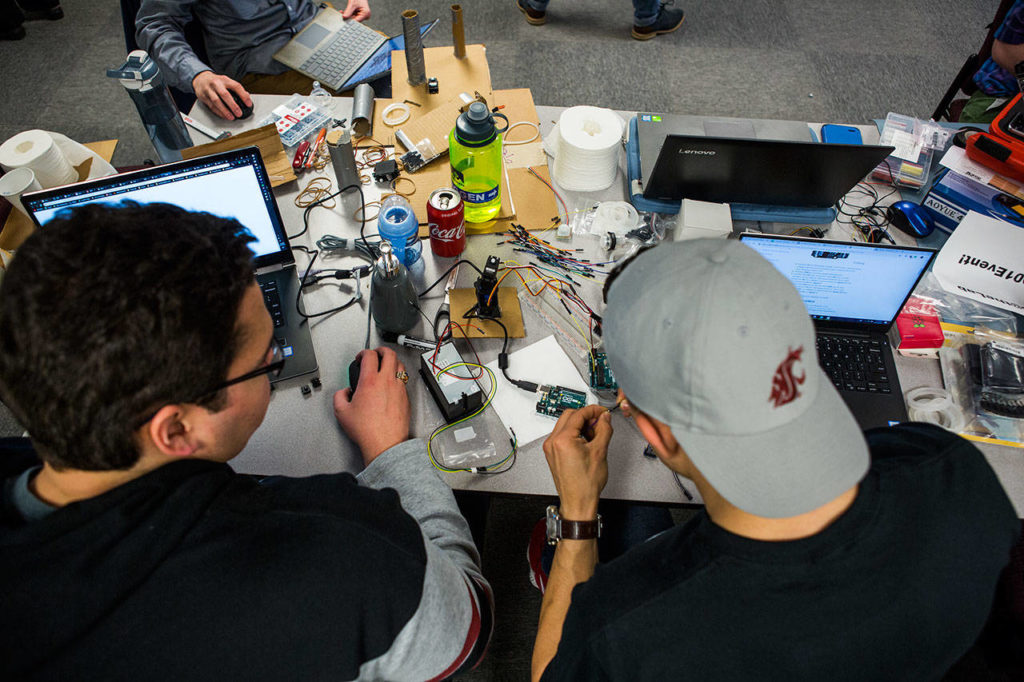

Seven teams of three and four students were given a “mystery bag” containing two technology items, such as electronic sensors or a tiny computer, and two household items, “like a Styrofoam head, rubber duck or bubble wrap,” said Boll, who helped organize the event.

“The grab bags assure a level playing field,” said Jacob Murray. He’s the electrical engineering program coordinator and academic advisor for the WSU Everett chapter of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

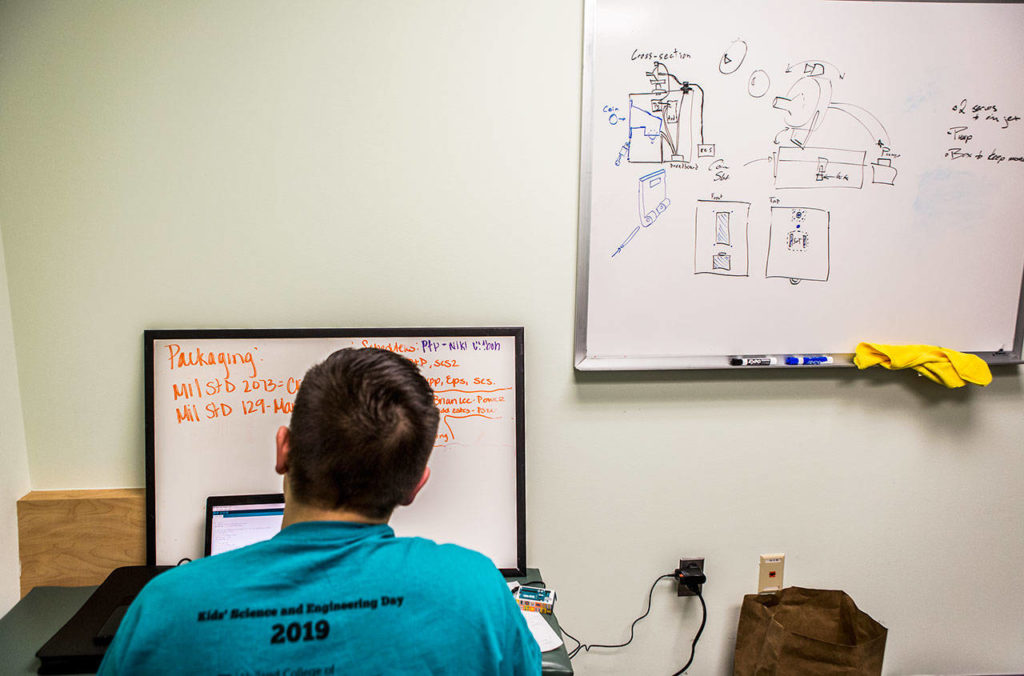

Team members began by brainstorming what kind of robot they could build with the parts they were given, and how to make it work.

“We’re here to flex our creativity muscle,” said Andrew Bragg, a software engineering student at WSU Everett. Bragg and his teammates created a flow chart for the design of a high-tech toilet paper dispenser.

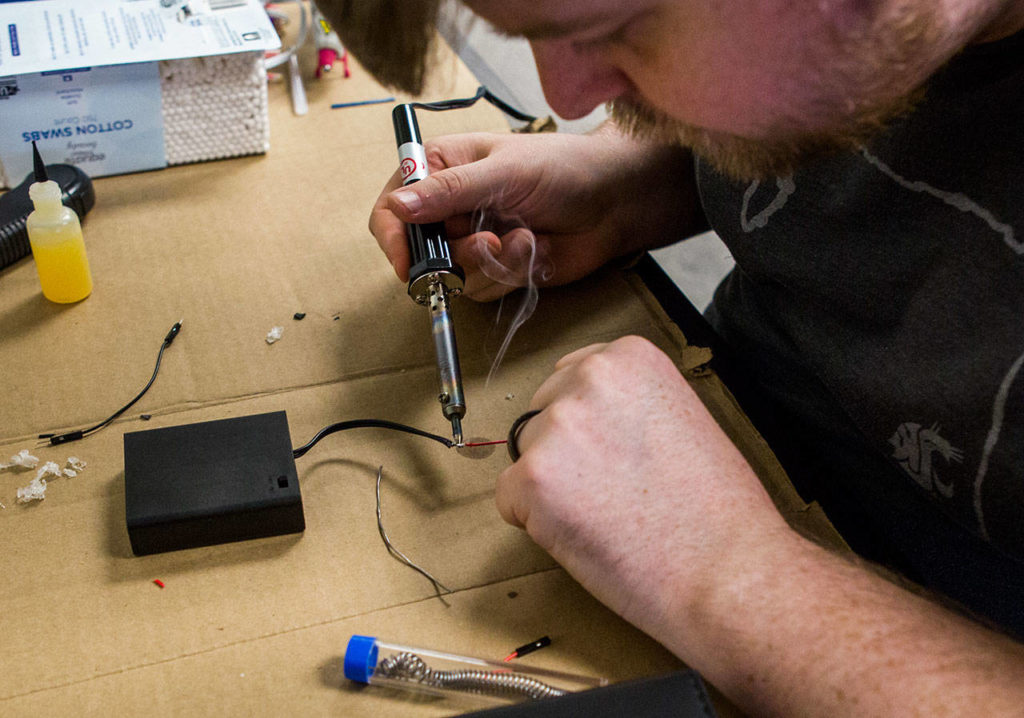

Participants spread out the contents of their grab bags on tables in the middle of the lab’s work room or hunkered down with their laptops in small offices.

They toiled through the night, catching an hour or two of sleep in “the armchairs, on the floor or under tables,” said Boll.

When time’s-up was called 24 hours later, the clutter of components, cables and nuts and bolts had disappeared. In their place — robots!

“Being able to whip something up in 24 hours is not a simple task,” Murray said

“We give them 15 weeks in our classes.”

Among the yield: a robot that scooped trash off the floor and took a photo of it — for quality assurance; an interactive dog treat dispenser that squeaked; and a voice-activated robot that dispensed toilet paper paper when you picked up the custom-built app and said, “Paper, please.”

The winning bot was a Styrofoam mannequin head programmed to locate its target with an electronic sensor, aim and deliver a generous squirt of hand lotion from its nostril — all while playing the theme from the movie “Jaws.”

Performance, complexity and humor were among the judging criteria.

“You don’t have three months to solve a problem. You don’t have the option of crafting parts. You have 24 hours to hack it together with what you’re given,” Crandall said.

It’s not that different from the workplace, he said, “where you’re dealing with time and budget constraints.”

And you have to be a bulldog.

“As an engineer, you have to have the drive to try to say, ‘I can solve this,’ because in the real world we need you to solve really hard problems,” Crandall said.

“It’s really a think-a-thon,” said Levi Cline, who is studying software engineering at WSU Everett and is a member of the trash-scooping team.

Now that you’ve built a crappy robot, put it on your resume.

Potential employers want to see this kind of innovation, what students have created outside of class and “beyond the grade,” said Murray. “This is something they can show off.”

The judges arrived Sunday morning to choose a winner. They included Joe Decuir, one of the designers of the Atari 2600, a 1977 game-changing video console, and executives from local tech companies: Fluke in Everett; Fujifilm SonoSite in Bothell, a medical imaging company; and thePlatform, a Seattle online-video publisher and division of Comcast.

“These are the sorts of projects that create skills that make you a valuable member of a development team,” said David Franklin, senior technical program manager at thePlatform. “It’s great resume material, and it makes me smile.”

Gina Kelly, a vice president at FujiFilm, said she would be looking for students that could explain “the why of their product — quickly and clearly,” a skill she looks for in job candidates. “You need to be able to articulate what problem your product is there to solve,” Kelly said.

George Allen, director of strategy and planning at Fluke, looked for diversity and innovation.

The more diverse your team, the better the results, Allen said. “People bring different experiences and points of view to any given project,” he explained.

At the close of the event, students agreed.

Teams comprised of members of different programs — such as mechanical, electrical or software engineering — fared better than those comprised of students from a single discipline, WSU advisor Murray said.

“The consensus from students, after they had some sleep, is let’s do this again, let’s make it a tradition,” Murray said.

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097. Twitter: JanicePods.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.