EVERETT — You wouldn’t buy a set of snow tires that hasn’t been tested on snow and ice or a dune-buggy that hasn’t tackled a sand dune.

It’s the same for engineers who design lunar landers and martian probes and want to know that their equipment can handle the terrain before launching a multi-million-dollar device into space.

The price of failure is steep.

Landing “something softly on the moon” costs about $750,000 per pound, said Vince Roux, who co-founded Off Planet Research with mechanical engineer Melissa Roth in 2015.

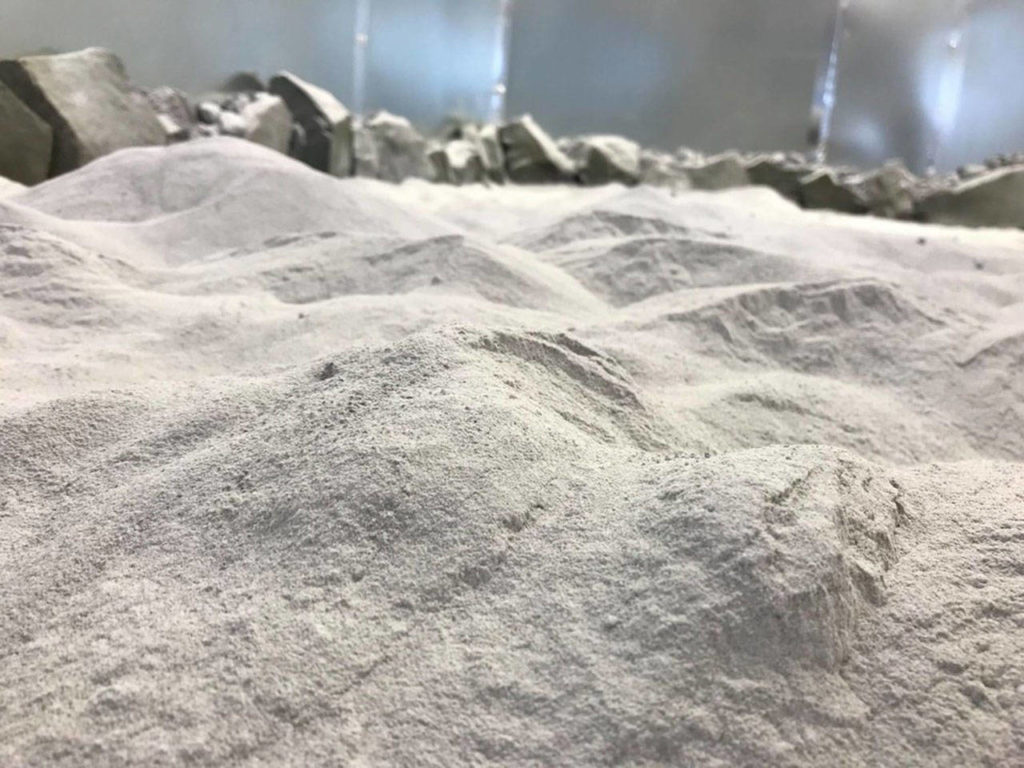

The company creates soil and ice samples that simulate the moon and other extraterrestrial soils, allowing researchers to test their contraptions here on earth. Its lunar simulants are modeled after samples and research gathered by the various Apollo missions.

“Our job is making sure it’s a successful mission,” Roux said.

Now, Off Planet Research is undertaking a journey of its own. The firm is relocating from Lacey, Washington to the Port of Everett where it will become the anchor tenant for the port’s new Maritime, Exploration and Innovation Complex.

The complex, which occupies the former Ameron pole manufacturing site located between 10th and 13th streets along West Marine View Drive, offers space for ocean and space-related ventures and startups.

Its launch “marks the start of an exciting new chapter for the Port of Everett and Snohomish County,” Port CEO Lisa Lefeber said.

Off Planet Research joins Snohomish County’s emerging outer space cluster, which has gained a foothold amid the region’s aerospace industry.

“This brings us closer to some potential clients,” Roth said of the move to Everett.

Last year, a firm associated with Blue Origin, the Kent-based spacecraft company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, paid $5 million for a six-acre tract in Arlington. Though not specifically space-oriented, two electric aircraft companies, magniX and Eviation, moved their operations to the county in 2020 as well.

In all, Washington is home to more than three dozen space-related companies including Blue Origin, Aerojet Rocketdyne, SpaceX, Spaceflight Industries and Tethers Unlimited, according to the state Department of Commerce.

Along with office and research equipment, Off Planet Research will transfer 40 tons of soil to its new digs — the equivalent of moving the house and the front yard.

The tonnage is used to create custom soils, in quantities ranging from a few ounces to hundreds of pounds, depending on the client.

On the moon and beyond, soil conditions can differ dramatically from one location to the next — just as they do on earth. The key to engineering a lunar device that functions properly is knowing the type of soil it’s likely to encounter, Roth said. “Think about putting up a telephone pole in the Vermont countryside versus planting one in a Florida swamp,” she said by way of an earthly example.

NASA recently gave up on a heat probe it sent to Mars in 2018 as part of InSight, a $825 million mission. The 16-inch probe, nicknamed ‘mole’ was to have burrowed into the regolith — the mix of dust, dirt and rocks that exists on and below the surface — and record the planet’s internal temperature, data that could provide clues to the red planet’s evolution and geology.

But the probe met with soil that unexpectedly clumped, preventing it from hammering itself to a sufficient depth. The little pile driver’s design was based on soil seen by previous Mars missions, “soil that proved very different from what the mole encountered,” NASA said in a statement.

“Mars and our heroic mole remain incompatible,” said Tilman Spohn, lead investigator with the German Aerospace Center, which designed and built the gadget. “Fortunately, we’ve learned a lot that will benefit future missions that attempt to dig into the subsurface,” Spohn added.

Off Planet Research wasn’t involved in the project, but it illustrates what can happen with a mismatch.

For now, the company’s focus is on the moon, “but in the future we want to support testing for missions to Mars and other planets,” Roth said.

Lunar dust can be as fine as cake flour and yet abrasive. On the earth, water, ice, microbes and other weathering processes tend “to round particles and break them down,” said Roux. Not so on the moon, where there’s no wind and temperatures can range from 253 degrees Fahrenheit during the day to 243 degrees below zero at night.

Those tiny but course particles can create tears in a spacesuit or collect inside equipment and cause the mechanism to seize up, Roux said.

The first spacesuits that went to the moon were made by ILC Dover, a division of Playtex, and were designed to withstand the dusty onslaught. Even a small tear in one of the 21-layer spacesuits could have spelled disaster for astronauts, causing the garment to deflate and lose pressure, Roux said.

Off Planet Research also creates simulants for researchers who hope one day to cultivate the moon and use lunar soil to plant corn or grow lettuce.

Creating “fertile” soil from lunar regolith is another challenge that’s best tackled here on the blue planet, Roth said.

Moon dwellers will probably need to “live off the land and utilize resources that are already there,” and make their own drinkable water and breathable air onsite, Roth said.

One resource that can be tapped is the lunar soil, which contains high levels of oxygen and small amounts of hydrogen, the two ingredients for H2O.

The company’s simulants allow scientists to “practice” extracting oxygen and water from the lunar crust — and save on shipping costs.

Shipping water to the moon in quantity — that would be an expensive proposition, said Roux.

Janice Podsada; jpodsada@heraldnet.com; 425-339-3097: Twitter: JanicePods

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.