LANGLEY — If only the story pole could talk.

Fifty feet tall, it has peered down on generations of families who made the annual summertime trip to the Island County Fairgrounds on Whidbey Island to see the 4-H exhibits, eat curly fries by the cart load and scream in delight on carnival rides.

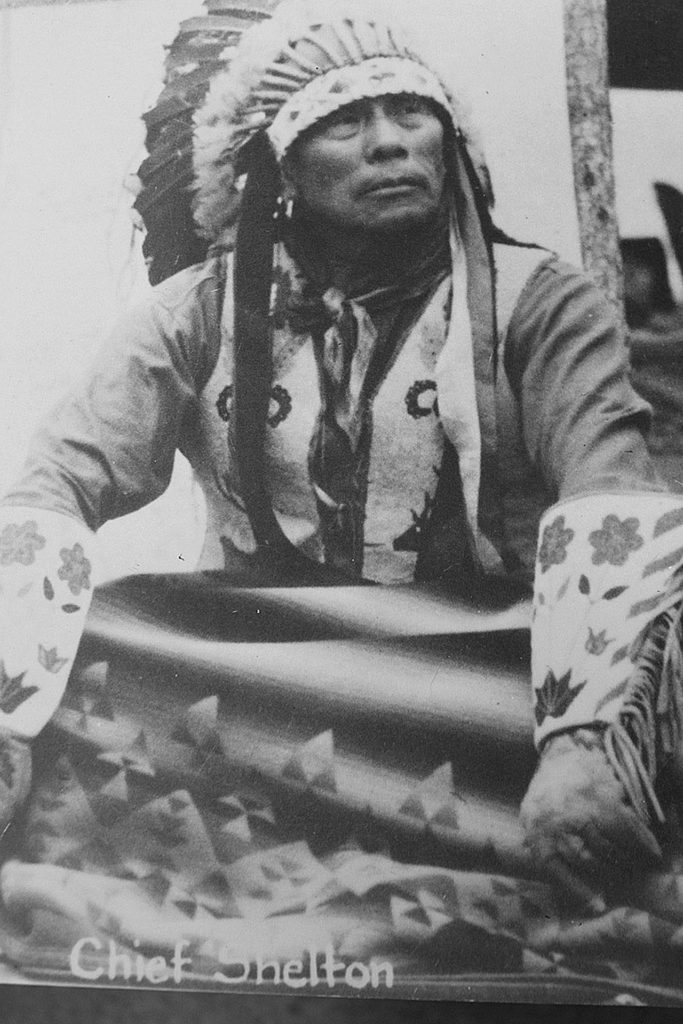

William Shelton, the last chief of the Snohomish Tribe and a well-known carver, was believed to be the artist of the fairgrounds pole. He carved many story poles in his lifetime, a few of which are still around today.

But a local historian now says that it isn’t a Shelton story pole — only one created in his style — and is working to uncover the story of the true carver.

Curators and carvers with the Tulalip Tribes examined the fairgrounds pole and identified it as a Shelton pole. But the story pole’s history has taken a dramatic turn: South Whidbey historian Bill Haroldson is piecing together a different origin story.

“Paul Cunningham (may have) carved the pole, and he had this older Native American telling him what to carve, what order to carve in and exactly what paint to use,” said Haroldson, president of the South Whidbey Historical Society.

Cunningham’s nephew, Jim Brevig, 87, told Haroldson that two poles were carved on the family’s Bayview property, but he’s unsure of the exact year. Other relatives also recall the scene of a native man passing along his skills to Cunningham, who was white.

“There were two tall totem poles and two short ones in my grandfather’s yard,” said Cunningham’s grandson, Albert Hagglund, 83. “There was an Indian showing him how to carve it.”

Tessa Campbell, curator with the Tulalip Tribes, said she’s been unable to find any historic photos or documentation proving Shelton carved the pole. She has, however, found a connection between Shelton and Cunningham.

“We have located archival materials in our collection that depict that Shelton and Cunningham were good friends,” she said. “We have photos of Cunningham and newspaper articles about them giving public presentations together.”

Who carved the fairgrounds pole, what story is being told by its carvings, how it ended up on the fairgrounds and what year it was erected there remain mysteries, Haroldson said.

Consulting longtime Whidbey families, such as the Gabeleins, Skarbergs and Hagglunds, was part of Haroldson’s detective work.

“I’ve been a little unnerved by this,” he admitted. “We had a pretty straightforward story. Now the only definitive answer we have is, ‘We don’t know.’ ”

Shelton, who was raised on Whidbey Island, served as an ambassador between the Snohomish people and the federal government. He, along with his daughter, would demonstrate native dancing, singing, drumming and storytelling at civic events around Puget Sound.

In 1912, Shelton, then 44, was impelled to create story poles to preserve the traditions and oral histories of his culture. A story pole differs from a totem pole, in that a totem pole tells a tribal or family story, while a story pole illustrates and passes down Native American legends and folktales.

From 1912, with the carving of his first story pole for the Tulalip Indian Reservation, to his death in 1938, Shelton carved at least 16 poles for public display across the United States. He also made numerous miniature story poles for private collections.

Crafted from Western red cedar, the fairgrounds pole could be what’s known as a teaching pole. Like other Shelton poles, figures are carved in high relief, giving them a three-dimensional look.

An eagle rests on top with wings spread and a native man with a single feather headdress anchors the base. In between are a rock, an octopus holding a salmon, a bird, a bushy-tailed fox, a whale, a mouse standing on a pedestal, a spider, a six-rayed sea star and two faces.

Another of Shelton’s story poles stood for 70 years on the capital grounds in Olympia before deterioration forced its removal.

The Burke Museum at the University of Washington also has a Shelton story pole that stood for decades in an Illinois town park that it hopes to restore.

The Island County Fairgrounds pole in Langley was taken down last month by the Port of South Whidbey for safety reasons and for restoration assessment. After more than 70 years of being exposed to the elements, its base is rotted and damaged. The port owns and maintains the fairgrounds.

“It is our intention to have the Tulalip Tribes restore the story pole,” said Angi Mozer, outgoing port executive director, “but we will need to pay for the restoration.”

But Haroldson is worried. If its history remains a mystery, plans to refurbish it may be altered, he said. Many questions remain.

Was it on loan to the fairgrounds by the Cunningham family? Was there a signed agreement that’s since disappeared? And if the pole isn’t indigenous art, is it still worth preserving?

To the last question, Haroldson offers a resounding, “Yes.”

“We do feel it is an artifact of William Shelton and of Whidbey Island,” he said. “It was carved in the Shelton tradition.

“The fairgrounds pole remains as a legacy of William Shelton and his efforts to bridge the gap between Native America and White America.”

Got a clue?

If you have information or historical photos of the story pole on Whidbey Island, email Bill Haroldson at wharolds@whidbey.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.