By Mary Preus

Special to The Herald

In the mid 1930s, a group of wealthy Everett businessmen eyed an attractive 20-acre parcel on the eastern shores of Lake Goodwin, thinking it would make a nice golf course.

The postmaster in East Stanwood had other ideas for the property. Snohomish County folks didn’t need a golf course, she figured. They needed a park.

Then she rolled up her sleeves and led a campaign to make that happen.

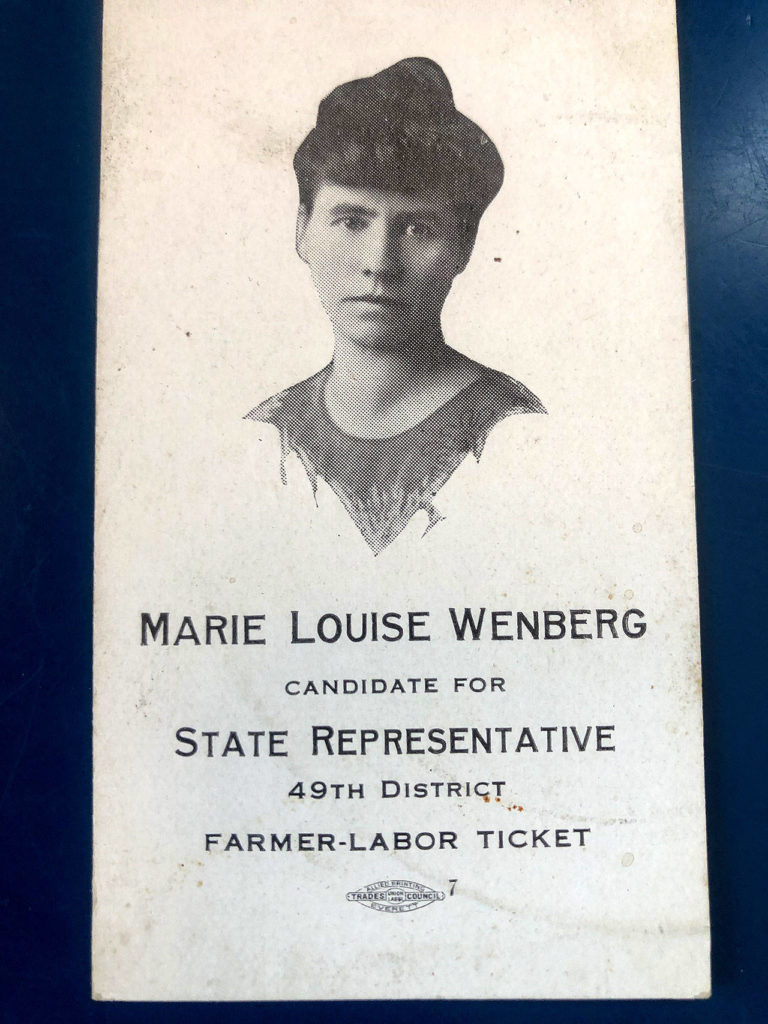

Her name was Marie Louise Wenberg, and she was my grandmother.

On Dec. 18, 2018, The Daily Herald reported on a nearly $3 million project at the now 46-acre park that upgraded the swimming area and boat launch, and added a fixed dock.

The article stated that the county park is “believed to have started as a donation from the Wenberg family in the 1930s.”

But that’s not exactly the case.

My grandparents — Oscar and Marie Louise Wenberg — were not wealthy. They were community activists who were members of the populist Farmer-Labor Party, which fought against the monied interests of the time.

I knew my grandparents didn’t have the kind of money to own lakefront property and give it away. They were always hard-working and barely making it, in farming and teaching. They were dedicated to public electric power and organized labor.

I wanted to explain who they were and what they did to make this happen. They didn’t give a gift, they worked on it and they risked for it. And they believed in it. They believed in public ownership of a lot of things. They were very progressive and idealistic.

Eighty years after Wenberg County Park was created, their story is well worth telling.

Louise, as she was known, worked for Pacific Lutheran Academy, now Pacific Lutheran University, in Parkland because she could not afford tuition at the college. She studied teaching and graduated from PLU in 1906. She taught until about 1910. She resigned before getting married, but got back into teaching in 1930.

She and Oscar married in 1911. In 1913, they bought a small farm near Florence, south of Stanwood. Their daughter Marie, my mother, was born in 1916, her brother, Johan, a year later.

Louise and Oscar became labor activists, with “Public Parks and Public Power” as their slogan. In 1922, Louise ran for the state Legislature on the Farmer-Labor ticket, which promoted fair labor rights. She finished in third place, behind two Republicans. She never ran again, but Oscar won a seat in the House of Representatives in 1939 as a supporter of labor, pensions, the Grange and public utilities.

In 1935, well into the Great Depression, Louise became postmaster in East Stanwood (East and West Stanwood were separate towns back then). She was elected president of the Snohomish County Rural Park Association a year later.

During that era of mass unemployment and suffering, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration stepped in to provide jobs and stimulate the economy by funding infrastructure and arts projects.

Through the WPA, the federal government offered 70% of the money for new parks, but local jurisdictions had to come up with the rest. My grandmother was determined to secure government funds for a park on Lake Goodwin.

In 1936, she began a campaign to raise $1,500 to purchase the lakefront property from C.D. Hillman for a county park.

Fundraising during the Depression was difficult, and her campaign to raise the money faltered. When the situation became desperate, the Wenbergs took out an $800 mortgage on their house and used it as a down payment to secure the property.

Within a few years, Louise’s efforts had paid off.

According to an article published by the Stanwood Area Historical Society, as Snohomish County Rural Park Association president, she dedicated the new park in 1939.

The Twin City News reported on Nov. 9, 1939, that “the park will be known hereafter as Wenberg Park, honoring Mrs. Louise Wenberg, through whose untiring efforts the work was carried on.”

According to the 1939 article, the WPA contributed $8,160 to park expenses. Which means the county share was about $2,450.

Johan Wenberg’s widow, Louise B.W. Luce, 95, remembers that my grandmother spent her own money on fire pits and metal grates, and planted hundreds of daffodil bulbs to beautify the park.

My aunt also remembers that owners of nearby resorts took down signs for the park because they didn’t want the competition of free swimming, boating and camping.

Eventually, the Wenbergs’ loan was repaid. The park named for Louise Wenberg was part of the state system for many years, reverting to county ownership in 2009. Oscar died of a stroke in 1952 at 71. Louise died in 1972 at 84.

As a young child, I often stayed with my grandparents at their modest Stanwood home, surrounded by Grandma’s lush gardens. Together, we often visited the park, where I remember the splash and spray of water from the hand pumps, and the clang of horseshoes against metal posts in the horseshoe pits.

My four siblings and I are proud of the Wenberg legacy, especially the crucial role played by our tenacious grandmother.

When the property their home stood on was sold and a new fire station built, Louise Luce requested that a plaque be installed to note that the property was formerly the home of Louise and Oscar Wenberg, founders of Wenberg Park. It’s not too late to make that happen.

Mary Preus, 73, owned the Silver Bay Herb Farm in Silverdale for nearly 20 years. A veteran gardener, she is the author of “The Leek Cookbook,” “A Little Book of Herbs for Cooking,” “Growing Herbs” and “The Northwest Herblover’s Handbook.” She now lives in Seattle.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.