STANWOOD — The man with a chipped front tooth checked into a SeaTac motel with his wife and infant son on a chilly weekend in late fall.

He was helping friend Bob Helberg with a move from Arizona. As the man left the motel with Helberg around 10:30 a.m. Sunday, Dec. 17, 1978, he told his wife that if he wasn’t back by noon, to go ahead and rent the room another night.

Only Helberg returned. He showed up at a friend’s house around 3 a.m. that Monday, near the motel. He set a big handgun on the dining room table.

“Ron’s not back,” he told the man’s distraught wife. “It was probably a contract hit.”

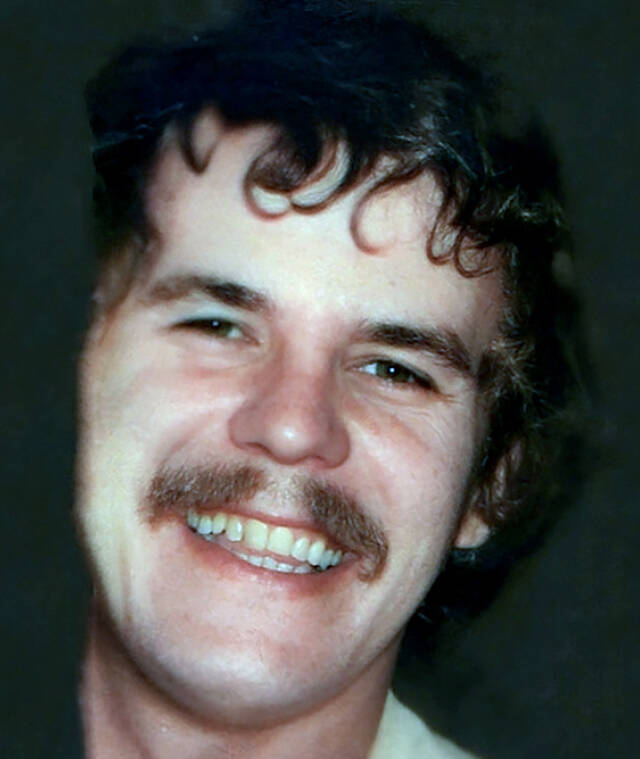

Ronald David Chambers, a Vietnam War veteran from Rome, Georgia, vanished that day at age 28. His whereabouts became a mystery buried deep in King County’s cold case files.

After four decades, Snohomish County investigators have determined through DNA that Chambers’ body actually had been found in 1980, in a patch of woods east of Stanwood and over 60 miles north of SeaTac. Those unidentified bones had been known to investigators as John Doe No. 3, or the Stanwood Bryant Doe.

It took nine tries from four labs to get a good DNA sample out of the unearthed remains. If not for advances in genetic technology, combined with the power of forensic genealogical research, the case would have stayed cold.

The Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office confirmed the identity Friday.

“I watched my mother grieve for 25 years for her son, wondering where he was and what happened to him,” Chambers’ sister, Judy Phillips, said in a written statement. “She carried that grief until the day she died. At 12 years old I lost one of the most important people in my life, my big brother. And today, thanks to the determination and hard work of so many men and women that worked my brother’s case, we are able to bring him home after so many years.”

King County investigators had long suspected Helberg in the disappearance. But without a body or other evidence, it couldn’t be proved. Helberg died in a California prison in the 1990s, and any account of Chambers’ last hours may have died with him.

The front row

On Aug. 3, 1980, a man found the human skull on his property at a bend in Pilchuck Creek. His neighbor’s dog had also come home with bones.

Over two days, the deputy coroner combed a shallow grave on the wooded property with the help of sheriff’s deputies, finding pieces of a man’s rib cage, vertebrae, arm bones, pieces of leg bones, a mandible with “exceptional dental work” — but no clothing, jewelry or a hint of the man’s identity.

One clue left little doubt of how the nameless man died. He suffered a gunshot wound to the back of his skull.

The human body filed under case number 80-8-561 was sent to the Center for Human Identification at Colorado State University, where Dr. Michael Charney used the skull to reconstruct a face out of clay. Charney believed the remains came from a white man, possibly with some Native American heritage, most likely age 23 to 28. His height was estimated at 5-foot-5¾ to 5-foot-9¼. An image of his crude clay sculpture was released to the public in November 1980. Charney returned the remains in the spring.

Today, the medical examiner’s office would have kept the skeleton secure until it had been identified. But this was another era. The John Doe was buried May 26, 1981, in section G, lot 393, row 1 of the Arlington Municipal Cemetery. The body stayed in the ground for 30 years, with little to no movement in the case.

Basic details about the evidence were entered into the database NamUs and the FBI’s National Crime Information Center in 2008, as Snohomish County sheriff’s detective Jim Scharf and his small team of investigators began reviving cold cases and aiming to solve them through DNA.

Under the watch of investigators, the grave was exhumed July 20, 2011. State forensic anthropologist Dr. Kathy Taylor examined the bones and gave a far broader estimate of the man’s height — 5-foot-3 to 5-foot-11. She also expanded the possible age range, 18 to 50.

Investigators sent bone to the University of North Texas to upload a genetic profile into the federal database CODIS. But lab workers couldn’t get a usable sample. So the Snohomish County Medical Examiner’s Office sent a tooth. Again, there wasn’t enough DNA.

A forensic odontologist looked at the Stanwood Bryant Doe’s teeth in early 2014. Fresh X-rays were uploaded to NamUs, helping rule out dozens of possible matches. Forensic artist Natalie Murry sketched an updated facial reconstruction based on the skull and jaw in 2016, with the hope it would jog the memory of a friend or family member.

Cold case detectives took tips over the years. One woman thought it could be her father, a dentist missing from Pierce County since the 1970s. A Skagit County detective offered a list of names of missing people ruled out in another 1980 John Doe case near Concrete, as well as hitchhikers.

One name came up as early as 2011, when Scharf checked in with King County. This guy had been missing from SeaTac since December 1978.

‘Person of interest’

Their car had broken down that week, so Chambers and his wife, Mary, left it at their friends’ house, where they had been staying for at least a couple of weeks, according to what the wife told Scharf. Their son wasn’t quite a year old.

On a Friday evening, everyone went to dinner together. Instead of going back to the house, the couple went to a motel. Two days later, Chambers left in a rental car. The last time his wife saw him, she later recalled, he wore brown heavy leather boots. She also offered another odd detail: All of a sudden at about 1:30 p.m., their child wouldn’t stop screaming.

Helberg called. He was on his way back. He came driving the rental car, alone. When he said it was a “contract hit,” Mary asked him what he meant. Helberg just repeated: “A contract hit,” and he claimed someone had probably been after him, not Chambers.

“He knew Chambers was dead at that point and nobody else did,” Scharf said Friday. “It took us 41 years to be able to figure it out.”

Helberg offered to help the wife with her things at the motel. They needed to fly home. But before they left on separate planes, she recalled asking Helberg if he had anything to do with what happened to her husband. Helberg clenched his jaw.

He answered, “No.”

Chambers’ biography in a police report is brief. Born in Rome, Georgia, to Riblee Jacobs and Samuel Chambers, a veteran of World War II and the Korean War. He had a brother and a sister. Ron Chambers served as a Marine. He did a tour in Vietnam in early 1968. Then he spent time in the inactive reserves until 1975.

Police suspected him of being caught up in “minor drug use.” Records about him are scarce.

The family reported Chambers missing in 1979.

Helberg, then 42, had drug connections — “maybe at a higher level than street level,” Scharf said. He sometimes borrowed a brother’s name as an alias. Detectives believe Helberg was a “self-proclaimed hitman.”

“He’s a person of interest,” Scharf said, “in a couple of other murders in another jurisdiction.”

The suspected killer died March 29, 1993, at a federal prison in Lompoc, California.

Just after Chambers went missing, his wife asked Helberg: “Why would anyone want to hurt Ronnie or (you)?”

He wouldn’t answer.

‘A long time’

Historic aerial photos show the 2500 block of Stanwood Bryant Road hasn’t changed much since Aug. 3, 1980. The creek flows from the foothills of the Cascades, and there’s a wide gravel bar with nothing but evergreen trees on either side.

The landowner who found the John Doe body was in his 40s. Back then it was a place for the family to go camping. They didn’t build a real home east of Stanwood, at the end of a quarter-mile driveway, until 17 years later.

The ever-evolving landscape of molecular biology, on the other hand, has revolutionized policing in many ways over the past four decades. And in Snohomish County, the cold case team led by Scharf has been using forensic genealogy to crack long-unsolved cases since 2018.

If you can extract crime scene DNA, or in this case DNA from weathered bones, a forensic lab can upload the genetic profile into public ancestry databases — for example, the free third-party site GEDmatch. From there a genealogist can identify the unknown person, either a suspect or a victim, by comparing the profile with millions of people searching for relatives. Often a second-cousin match or closer can quickly guide a researcher to the spot where two family trees intersect. It’s the same technique that was used to identify and arrest the Golden State Killer in California.

Quietly, from beyond the grave, pieces of the Stanwood Bryant man crisscrossed the United States.

In 2018, the medical examiner’s office sent bones to DNA Solutions in Oklahoma. The private lab could only pull “very small amounts of degraded DNA,” not enough for GEDmatch.

In 2020, federal grant money allowed for another try. Bone arrived at Bode Technology in Virginia. A partial profile was uploaded into CODIS, an FBI program with DNA profiles from felons in all 50 states.

Around the same time, the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office received funding help from the FBI to send the mandible and other bones to Othram Labs in Texas. This time, the profile was complete enough to upload to Family Tree DNA. The genetic testing company has marketed its sharing of customers’ data with police as a positive, not a privacy concern. “Help us catch killers is now the new advertising angle for DNA companies,” read one headline in MIT Technology Review.

On Nov. 16, 2021, in-house genetic genealogists at Othram emailed Scharf with a possible match: a man from Rome, Georgia. Chambers had been presumed dead on Dec. 22, 1985.

Scharf called Chambers’ sister, who agreed to have her DNA tested for comparison. On Dec. 28, the results came back, confirming she was the John Doe’s sister.

Just to be certain, the medical examiner’s office dug up Chambers’ military dental records and sent them to forensic odontologist Dr. Gary Bell. And in February, he confirmed the teeth matched.

Chambers’ wife declined to speak with media Friday but released a brief statement.

“It’s been a long time,” Mary Chambers said. “He was 28, now he would be 71. I’m really happy to have this moment and bring him home. Thank you very much to everyone for your persistence and dedication to seeing this through.”

His sister thanked the detective for bringing her family “closure after so many years.” She struggled to find the right words.

“Ronnie was much more than just my big brother,” she said in writing. “He was a son and a little brother to our oldest sibling. He was a husband, a father, a friend, a Marine who fought for this country in Vietnam. He was so very loved and missed, and always will be.”

Police are seeking tips about anyone who knew Robert “Bob” Helberg from 1978 to 1985. Tips can be directed to the sheriff’s office at 425-388-3845.

Caleb Hutton: 425-339-3454; chutton@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @snocaleb.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.