The Pacific Northwest is ripe for a major earthquake — and shaking and tsunamis wouldn’t be the only threats from such an event, according to new research. Coastal land would also sink nearly seven feet, meaning people who survive the initial catastrophe would face severe flooding.

An earthquake in the Cascadia Subduction Zone with a magnitude greater than 8.0 could cause a sudden subsidence — the sinking of land — that, paired with rising sea levels, would enlarge floodplains expanding up to 115 square miles, found the study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We could have a disaster on the scale of Japan 2011 or Sumatra 2004,” said Tina Dura, the study’s lead author and an associate professor of natural hazards at Virginia Tech. “It’s the same kind of fault. It has the same capability of making a huge earthquake, tsunami and coastal subsidence.”

The sudden sinking of land could permanently alter coastal communities, which experience flooding during king tides or storm surges but could become more frequently inundated, Dura said.

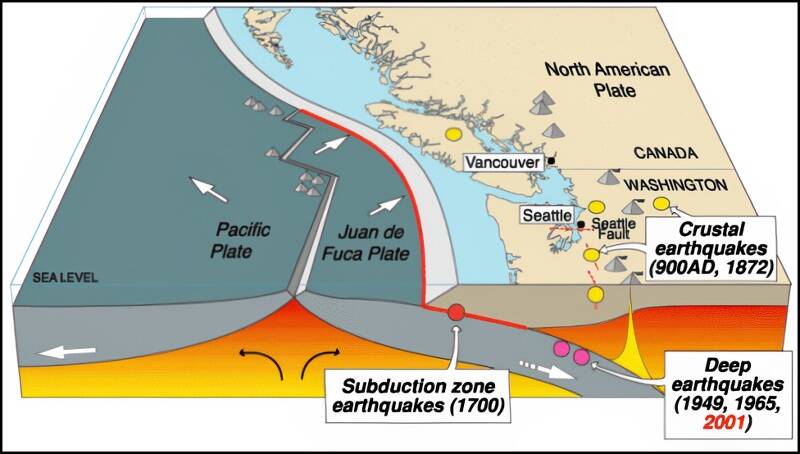

The Cascadia Subduction Zone, where one plate of Earth’s crust dives beneath another, stretches from Northern California to Canada’s Vancouver Island. It has been building up stresses for centuries that will eventually release in a catastrophic quake, scientists predict.

But they can’t say exactly when the Pacific Northwest’s “Big One” could strike. The last great earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone occurred in January 1700, and big events are typically separated by 450 to 500 years, Dura said. However, earthquakes are not “evenly spaced” every time, she noted.

“It could happen any day, but it might not happen till 2100,” Dura said. “We want to look at that because by that time, the climate-driven sea-level rise is expected to become a bigger problem along Cascadia.”

Taking predicted sea-level rise into account, the flood risk from a great earthquake in 2100 could be more than triple the risk that exists today, the study said.

Dura said coastal residents she’s spoken to often have not entirely grasped the ramifications of a great Pacific Northwest earthquake, which could generate a tsunami with waves up to 40 feet high, The Washington Post has reported.

“You have the tsunami evacuation signs, but they seem more like a novelty than any like serious thing,” Dura said. “People need to worry about it.”

One way to prepare is taking future risks into account when building infrastructure, a method called “resilience planning,” said Andrew Meigs, a professor of geology at Oregon State University who was not an author of the study.

If officials and residents in the Cascadia region ignore the threats, “the impact that it has on you will be substantially larger than if you elect to acknowledge that there’s the background sea-level change and the hazard is always going to be there,” Meigs said.

In the Pacific Northwest, Dura said, that would include rethinking locations of airports, wastewater treatment and agricultural lands as well as evacuation routes.

“My hope is just to get the word out there more so people can be prepared,” she said. “And we can have less impact, less loss of life and property.”

Carolyn Y. Johnson contributed to this report.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.