Inmates made the bricks used to build the Washington State Reformatory. The Monroe “smokestack” — now with its own Facebook page — spewed steam, not smoke. And the Evergreen State Fairgrounds was once part of the Snohomish County “poor farm.”

Those historical tidbits will be part of a free program, “Monroe’s Vanished Landmarks.” Presented by the Monroe Historical Society, it’s scheduled for 1 to 3 p.m. Saturday at the Monroe Library.

While not a landmark, one thing that vanished from the community was its original name.

What’s now Monroe was founded as Park Place in 1864, during the Civil War, said Dexter Taylor, a Monroe Historical Society volunteer who’ll present part of the program.

“It was just a natural place. Rivers divided there, and there was a lot of good farmland,” said Taylor, 67, whose pictorial book “Early Monroe” was published in 2013.

Settler Henry McClurg, the town’s founder, called it Park Place — now the name of a Monroe middle school. In 1860, McClurg claimed land where the Skykomish and Snoqualmie rivers met to form the Snohomish, according to a HistoryLink essay by the late Nellie Robertson, another chronicler of the city’s past.

In 1893, the county built what became known as the poor farm. Officially the County Farm and Hospital, it was a two-story “home for the ill, aged and indigent,” says the EvergreenHealth Monroe’s website. The hospital, formerly Valley General, sits where the poor farm once was.

North of the wood-frame poor farm building — torn down in 1929 — was a larger piece of county land. Now the fairgrounds, it was part of the poor farm where residents tended livestock and raised crops.

“This was pretty typical across the country,” Taylor said. In a newer building, the County Farm and Hospital operated until 1940. In 1935, Congress had enacted the Social Security Act, which helped the elderly.

Monroe, named for the nation’s fifth president, had 325 people when it was incorporated Dec. 20, 1902.

By 1907, the town’s Commercial Club had persuaded the state to build a reformatory there. Inmates in temporary quarters made the bricks used to build it.

“There was clay on the site,” said Tami Kinney, president of the Monroe Historical Society. Inmates made 15,000 bricks a day, she said.

Susan Biller, spokeswoman for the Monroe Correctional Complex, said the state has photos of inmates making the bricks used to construct a wall still in use. The 1910 Washington State Reformatory building now houses 770 inmates, out of the 2,499 men in all five facilities at the complex.

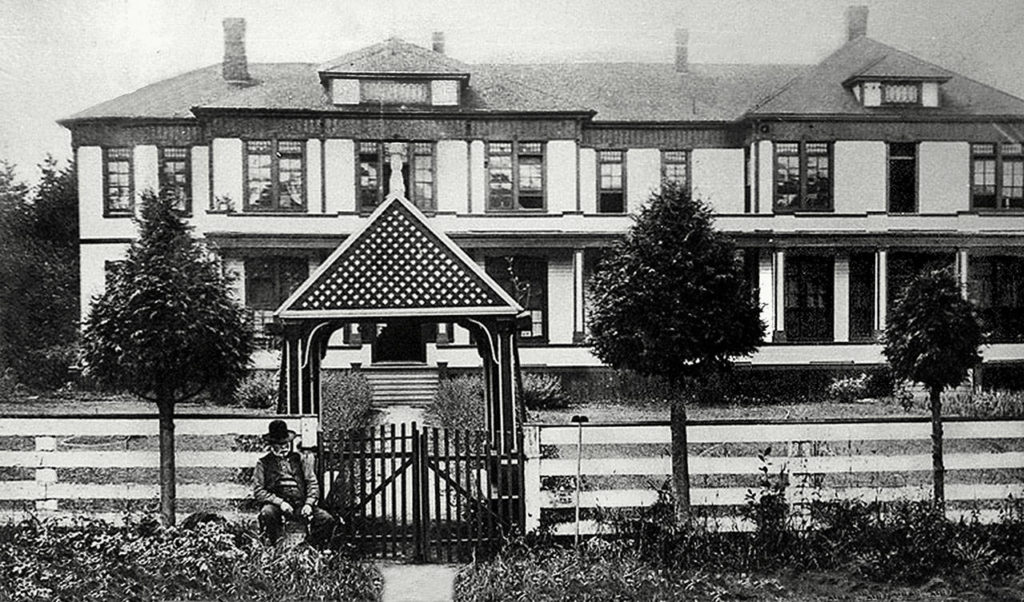

What’s no longer there is the original reformatory superintendent’s 1911 mansion. Cleon Roe, the first superintendent, lived there with his wife, Anna.

“It was beautiful,” Taylor said. The mansion was down the hill on landscaped grounds leading up to the reformatory. The ornate home was used for visiting dignitaries, Kinney said.

Neither Taylor nor Kinney know why it was demolished in the mid-1970s, and Biller didn’t have that information. It’s likely “they just didn’t want to put the upkeep into the whole thing,” Taylor said. “The superintendent was no longer living there.”

The mansion had “beautiful grounds cared for by inmates, and an elegant dining room,” said Kinney, adding that townspeople were upset by its demolition.

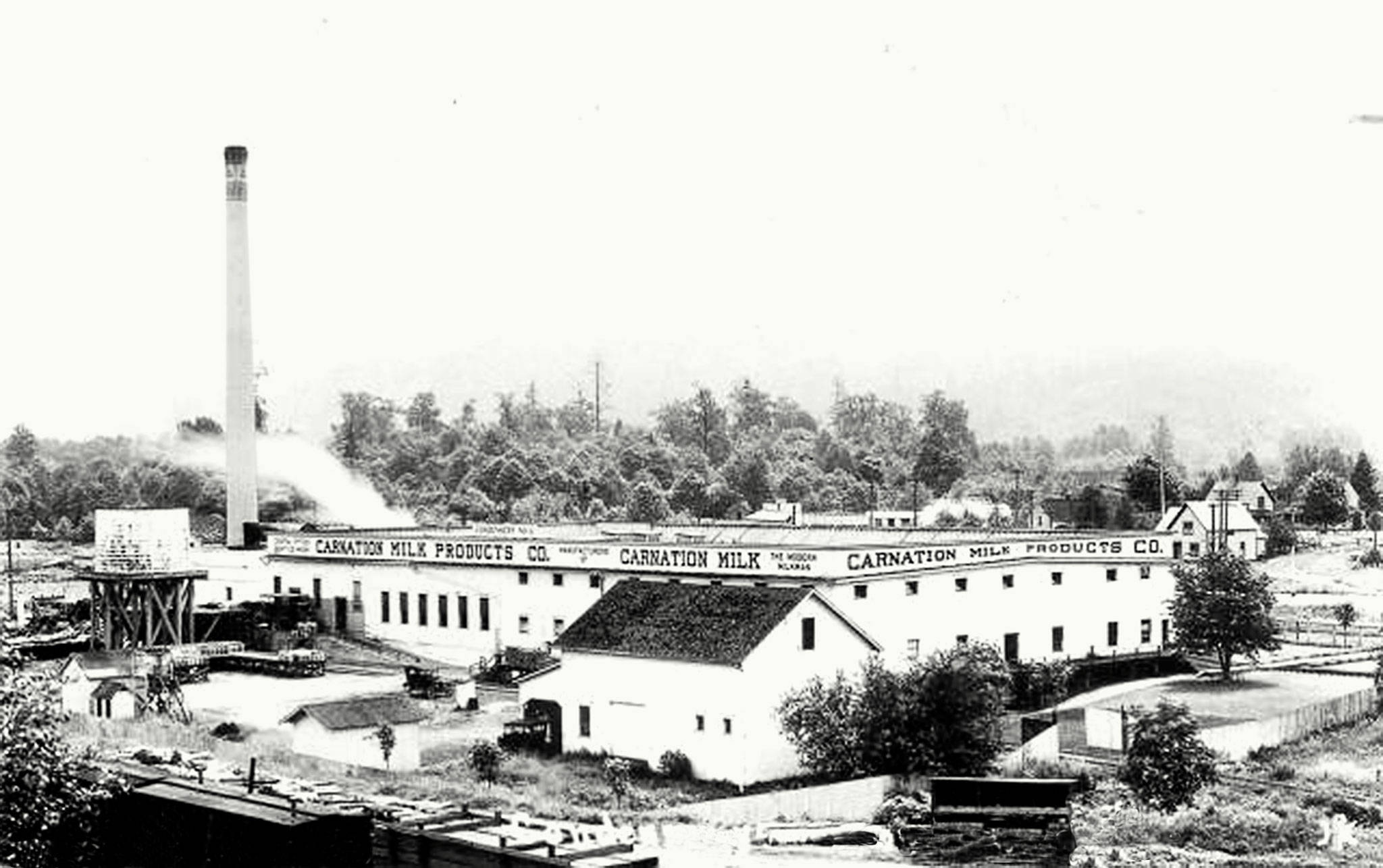

Still standing tall is the old steam stack, a relic of a Carnation milk condensery.

The Pacific Coast Condensed Milk Company, which made Carnation Milk, built the plant in 1908, and many locals worked there until 1929. Condensed milk was made there until 1912, according to HistoryLink. Later, milk was skimmed, with cream sent to other plants for butter. The Monroe plant made casein, a hard plastic-like byproduct.

In the late 1920s, Carnation consolidated Monroe operations with a Mount Vernon plant. In 1944, the abandoned facility was reopened for flax production. Fiber needed during World War II was made from flax, Taylor said. It operated only a few weeks before it burned down on March 23, 1944 — 75 years ago Saturday.

There was talk of tearing down the stack, Taylor said, but it was spared. In 2014, it was painted with a scene of Mount Index and evergreen trees. It’s on private property held by a shopping center owner, Taylor said.

Taylor hopes people will share stories at the program, adding to Monroe’s known history. He and Kinney know where one piece of history resides.

The poor farm’s bell is part of the Monroe Historical Society & Museum collection.

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

Lost landmarks

The Monroe Historical Society will present a free history program, “Monroe’s Vanished Landmarks,” 1 to 3 p.m. Saturday at the Monroe Library. The library is at 1070 Village Way, Monroe.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.