EVERETT — The barber’s letter to his only son is dated “12-7-41.”

By the time Daniel Luther Guisinger Sr. put pen to paper and wrote “Dear Son, This has been a hectic day, the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor began coming in about 11:50 a.m.,” the USS Oklahoma had been hit by at least eight torpedoes. Its crew had been strafed.

In the hellish chaos of Japan’s surprise attack, the battleship rolled over in about 50 feet of water, trapping hundreds of men inside.

“The only thing we can do is hope & pray,” the Everett father wrote in the letter that ends with “God Bless you, good bye for now, Dad.”

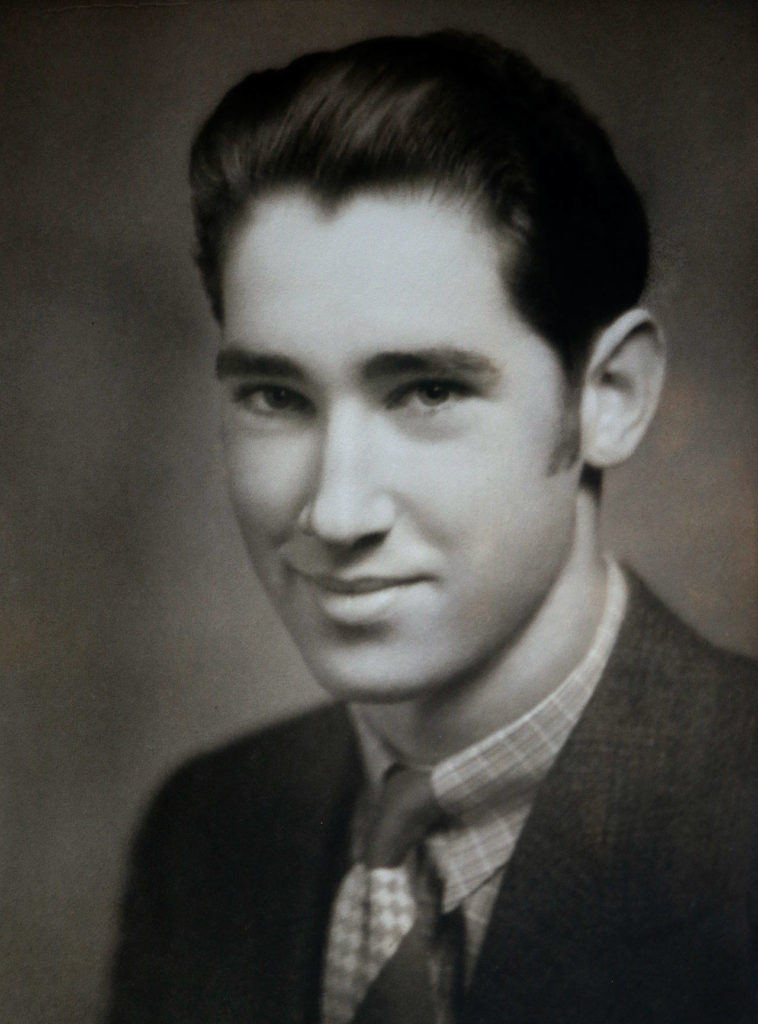

Daniel Luther Guisinger Jr., a 1938 graduate of Everett High School, was one of 429 men from the USS Oklahoma killed at Pearl Harbor. In all, the attack claimed 2,402 American lives, 1,177 from the USS Arizona, and launched the country into World War II.

Last weekend, Seaman 1st Class Daniel Guisinger Jr. came home.

Guisinger was buried April 27 at Everett’s Cypress Lawn Memorial Park. With military honors, in a ceremony attended by his many descendants, his cremated remains were laid to rest between the graves of his parents, Daniel Sr. and Inez Guisinger.

“I felt overwhelmed with gratitude,” said Judy Price, 74. Her late mother, Genevieve Guisinger Glover, was one of Daniel Guisinger’s two sisters — the sailor would have been her uncle. Price came from Selah, near Yakima, for the ceremony that Saturday.

“I did grow up hearing about Uncle Dan. Mother and her sister (Juanita Guisinger Jensen) and my grandparents doted on Danny, the only son,” said Price, who was born several years after Guisinger was killed. “When I was younger, it didn’t mean a whole lot. The older I’ve gotten, it means everything to me now.”

For decades, Guisinger’s remains were unidentified and buried in Honolulu at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, known as the “Punchbowl.” Nearly 400 men from the USS Oklahoma were buried as “unknowns.”

Through the work of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) and the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, his remains were identified last year at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. The agency announced that Guisinger had been identified using mitochondrial DNA, dental analysis and other evidence.

Dan Hoeglund, of Lake Stevens, spent months in touch with the federal agency and the Navy as he arranged for the memorial honoring his great-uncle.

“I’m the namesake,” said Hoeglund, 60. His late mother, Linda Hoeglund, was the eldest of Judy Price’s two sisters. Born in 1939, she was a year old when Guisinger joined the Navy.

In his eulogy at the cemetery, Hoeglund expressed appreciation for the military’s “unimaginable efforts” to account for service members lost in past wars. “Your efforts and diligence brought our family member home, now to rest alongside his parents,” he said.

“I was overwhelmed by the pageantry and patriotism of the service,” Hoeglund said at a family gathering at his home after the somber memorial. His son, Chris Hoeglund, agreed. “It was good to see all the family there to honor Daniel Guisinger’s life and service,” he said.

It was Judy Price and her 77-year-old sister, Lana Williams of Sequim, who accepted the folded American flag from Rear Adm. Linnea Sommer-Weddington at the cemetery. Before presenting it to the sisters, sailors held the unfolded flag over the urn with Guisinger’s ashes.

A chaplain from Naval Station Everett, Lt. Jisup Choi, presided over the military proceedings. The day’s quiet was punctuated by a ceremonial rifle team from Naval Base Kitsap. Seven team members with M14 rifles fired three volleys, honoring Guisinger with a 21-gun salute. A ceremonial bugler played taps. A sailor placed the urn into Guisinger’s freshly dug grave. One by one, loved ones scooped sand from a bucket, pouring it over the urn.

Sommer-Weddington, the rear admiral, had traveled to Everett from Nebraska, where she is with the U.S. Strategic Command at Offutt Air Force Base.

On April 24, family members who came from as far away as Wyoming and Utah also attended a planeside ceremony at Sea-Tac Airport. The casket bearing Guisinger’s remains was returned to his home state aboard a Delta Air Lines flight. It had come to Sea-Tac from Atlanta, but Guisinger’s remains made a longer trip. The journey originated in Nebraska.

An escort, Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Stephanie Kitchen, traveled on every flight that bore the casket. A Navy mortician, she is based in Millington, Tennessee. At the airport, after an honor guard placed the flag-draped casket in a shiny black hearse, Kitchen was in tears as she hugged Price and other members of the clan.

Young man of Everett

Daniel Guisinger, a prominent family’s cherished son and brother, was 21 when he died. In the late 1930s, Daniel Guisinger Sr. served in the state House of Representatives.

Price, the sailor’s niece, keeps a thick scrapbook filled with his pictures, articles and poignant letters.

In a letter Guisinger sent from Pearl Harbor nine days before the attack, he began with “Dear Folks,” and told his family “I’ve sent all my Xmas cards out.” And he mentioned a money order he’d be sending home with the hope of buying an engagement ring for his sweetheart, named Lily.

Among Price’s mementos is the chilling telegram sent Dec. 21, 1941, to the family home at 2709 Rockefeller Ave.: “The Navy Department deeply regrets to inform you that your son Daniel Luther Guisinger Jr. Seaman First Class Navy is missing following action in performance of his duty and in the service of his country … ”

Before enlisting in the Navy on Sept. 26, 1940, Guisinger passed up a prestigious entry into U.S. Army service. A letter from Congressman Mon Wallgren, who later became Washington’s 13th governor, as well as a 1937 newspaper article — “NW Boy Picked for West Point” — said Guisinger had been appointed to the United States Military Academy.

Yet a January 1938 letter to Wallgren from the War Department shows that Guisinger declined the West Point appointment.

“He had the opportunity but decided to join the Navy. I don’t know why,” Hoeglund said of his great-uncle, who was listed in Everett High’s 1938 Nesika yearbook as a three-year honor roll student.

Hoeglund is amazed that so many documents and letters — some returned by the Navy to the family — were saved. Some of Guisinger’s letters mentioned his little niece “Lindy,” who was Hoeglund’s mother Linda.

“I’m very honored to have ended up with it in my hands,” said Price, Hoeglund’s aunt.

The memory book has items from years after the Pearl Harbor attack.

One Everett Daily Herald article, from Memorial Day 1947, shows Daniel Sr. and Inez Guisinger being honored as one of Everett High’s more than 80 Gold Star families. Daniel Guisinger Jr. was the first Everett High graduate to be killed in what would be World War II. Inez Guisinger was the school’s first Gold Star mother of the war.

DNA identification

Hoeglund said his family had been preparing for his great-uncle’s burial since Oct. 23, 2018. That’s the day representatives from the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency visited his Aunt Lana Williams’ house in Sequim.

The identification of Guisinger was initially announced by the MIA agency on June 25, 2018. That announcement said his name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl cemetery, and that a rosette would be placed next to it showing he’d been accounted for.

Price, the sailor’s niece, had sent her DNA to the POW/MIA accounting agency. A cousin had done the same. “A year later, I got the phone call,” Price said.

The story of how Guisinger’s remains came home to Everett is a long one.

From December 1941 to June 1944, the Navy recovered the bodies of the Oklahoma’s dead. Initially buried in two other cemeteries in Hawaii, in 1947 they were disinterred. Staff at the Central Identification Laboratory at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii could only identify 35 men. By 1949, the unidentified remains had been buried in the Punchbowl cemetery. A military board had classified them as non-recoverable, including Guisinger.

The story’s most recent chapter began in 2015. With what The Washington Post described as “a fresh mandate from the Defense Department,” bones from the USS Oklahoma’s crew were exhumed from the Punchbowl cemetery. Most were brought to Nebraska, to a new lab in an old aircraft factory at Offutt Air Force Base.

In an article published Dec. 6, 2015, the Post described lab scientists’ enormous task. They work with bones that were submerged in oily water and later buried in caskets that rusted with time. Many of the dead were found in the battleship’s wreckage after it was righted in 1943.

At the USS Oklahoma Memorial near Pearl Harbor, 429 white marble pillars stand as a tribute to those lost in the attack.

As of Friday, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency had identified 206 sets of remains from the USS Oklahoma. There were 388 sets of remains disinterred in 2015, but a few were identified prior to that and are included in the 206, according to Sgt. 1st Class Kristen Duus, the agency’s chief of external communications.

The mission continues. On Wednesday, the DPAA announced that the remains of one more USS Oklahoma sailor, Navy Fireman 3rd Class Jasper L. Pue, had been identified. Pue joined the Navy in Texas.

Annie Cook, a descendant of Guisinger’s who lives in Wyoming, attended the Everett memorial and the ceremony at Sea-Tac. With a master’s degree in DNA analysis, she has worked for a private laboratory.

“The way DNA analysis works in this scenario, they tested mitochondrial DNA. Passed on through a maternal relative, it’s extremely resilient. They got a full match,” Cook explained. Guisinger’s DNA was taken from the pulp of a tooth, she added.

As Hoeglund was making arrangements for the Everett burial, Cook presented a guest lecture at Central Wyoming College about forensic DNA methods used to identify Guisinger. Although she read the report, about 140 pages, of how the identification was achieved, the experience went way beyond science.

She described her ancestor’s homecoming as “reverent, honoring, awe-inspiring.”

“This is close to home for me,” said Cook, whose mother is one of Hoeglund’s sisters.

Sailor’s story lives on

Had he lived, Guisinger would have been 99 now. Price said there was no thought of leaving her Uncle Daniel in Hawaii.

“We had the option of having him buried there, or having him buried at Arlington National Cemetery,” she said. “My sister and I agreed to bring him home.”

Nearly 78 years after the USS Oklahoma’s destruction and the deaths of so many, children were among descendants gathered at Sea-Tac and in Everett to honor Guisinger.

Annie and Cameron Cook brought their sons, 8-year-old Riot and Ronin, 5, from Wyoming to the memorial.

“The best thing for me — my kid, my son, he knows who this man is,” Annie Cook said. During one of the ceremonies, she noticed their 8-year-old singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” with his hand over his heart.

When Cook noted that four generations were at the cemetery to pay their last respects to a Pearl Harbor hero, Hoeglund said it was actually five generations. Guisinger’s parents, buried on either side of him, were there too, he said.

Seventy-seven years after writing “good bye for now,” a father was reunited with his son.

Judy Price’s son John Price flew from Pasco to be in Everett. Her grandchildren, Matthew, 19, and Paige, 22, were there, too. Price said she told her granddaughter, “I hope this will be passed on to your children.”

At Sea-Tac Airport the evening of April 24, Becca Weinberg was among family members awaiting the arrival of a Delta airliner at Gate A1. Weinberg, Hoeglund’s 25-year-old daughter, held her baby girl, Berkley. A few days shy of her first birthday, Berkley could be alive in 2120. And a century from now, she may still be telling the story of her great-great-great uncle, Daniel Guisinger Jr.

The sailor’s grave marker tells that story in brief: Along with his name, birth and death dates — Feb. 24, 1920–Dec. 7, 1941 — it says Purple Heart, USS Oklahoma, Pearl Harbor.

And in bronze, it tells another truth, assured by generations of Guisinger’s family and generations to come: “Never Forgotten.”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.