An open-pit mine that wasn’t: Ridge near Glacier Peak spared

Published 1:30 am Sunday, April 26, 2020

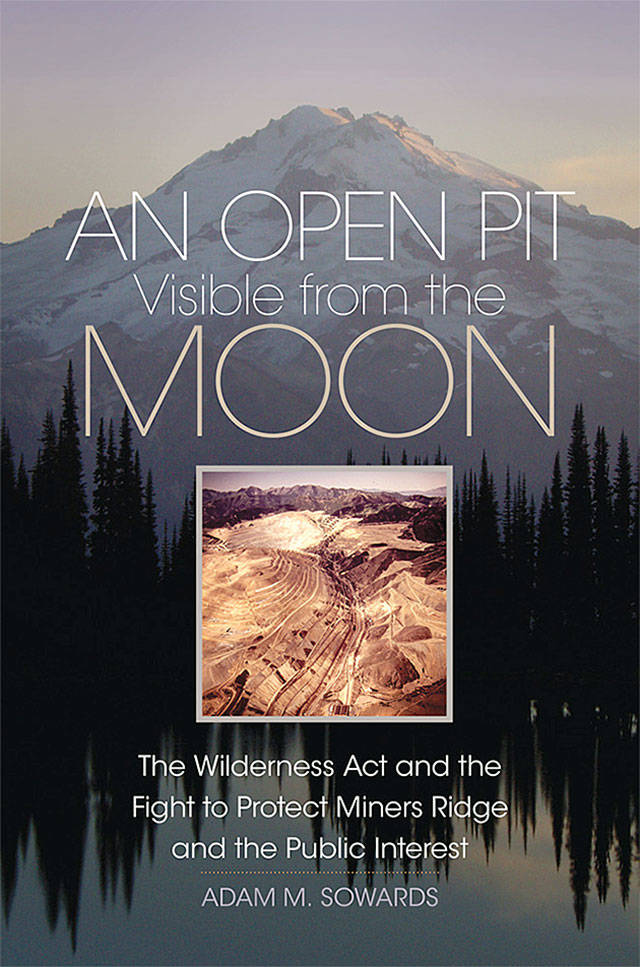

It has an intriguing title, “An Open Pit Visible from the Moon.” The new book by history professor and Marysville native Adam Sowards tells of a conservation battle waged a half-century ago. Ground zero in that fight to stop a copper mine was a remote place of beauty in Snohomish County.

Miners Ridge is east of Darrington and south of North Cascades National Park, in the Glacier Peak Wilderness. In 1966, just two years after Congress passed the Wilderness Act, the Kennecott Copper Corporation announced it intended to build an open-pit mine there.

“I think it was really well known in the late 1960s, but it had fallen out of collective memory,” Sowards, who teaches at the University of Idaho, said about the struggle that pitted environmental activists against business interests.

In the end, although Kennecott had every legal right to dig that pit — described by foes as nearly seven football fields wide and deep enough to contain the Space Needle — it did not happen. Although the company had patented mining claims in the 1950s and explored the area in the ’60s, the author credits outspoken foes of the mine for what is there today, unspoiled land.

Plummer Mountain, northeast of Glacier Peak, was the target for the copper it contained, Sowards wrote.

The fight was chronicled in one section of a previous book by John McPhee, “Encounters With the Archdruid,” which covers environmentalist David Brower’s conflicts with a mineral engineer.

Among activists whose views won out were towering figures in the environmental movement, including U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who led a protest hike, and Brock Evans, then Northwest representative of the Sierra Club.

Lesser known people, too, cared deeply about what would become of a place revered as one of the nation’s most spectacular.

Fred Darvill, a doctor from Mount Vernon, bought Kennecott stock so he could attend a shareholders meeting to show pictures of Glacier Peak and Image Lake. “He went to talk about beauty,” Sowards said. And an Oberlin College student, Benjamin Shaine, wrote a senior honors thesis about the issue, and worked to get scientists’ signatures on a petition presented to Kennecott executives.

A 1991 graduate of Marysville Pilchuck High School, the 46-year-old Sowards grew up on a farm where his family raised cows. He earned a bachelor’s degree in history at University of Puget Sound and graduate degrees from Arizona State University. He’s been at the University of Idaho 17 years, focusing on environmental history and the American West. Earlier, he taught at Everett and Shoreline community colleges.

Sowards is also the author of “The Environmental Justice: William O. Douglas and American Conservation,” and the editor of “Idaho’s Place: A New History of the Gem State.”

His boyhood home north of Marysville offered scenic views of the Cascades. In the 1960s, those mountains were luring a new generation of wilderness enthusiasts, but also drawing the attention of Kennecott. By the 1950s, the company was the nation’s largest copper producer.

Published this month by the University of Oklahoma Press, his book grew from an essay he wrote for a previous volume, “The Nature of Hope: Grassroots Organizing, Environmental Justice and Political Change,” edited by Char Miller and Jeff Crane.

“Since the nineteenth century, law had acknowledged mining as the highest use on public lands,” he wrote in that essay. “To Northwest conservationists, Miners Ridge, Glacier Peak and the North Cascades mattered a great deal. This was a protected landscape and a personal one.”

Talking about the issue just after Earth Day’s 50th anniversary, Sowards hesitated to call the story one of good versus evil.

“It’s more complicated than that. I don’t want to say anyone is evil,” he said.

His book’s subtitle is “The Wilderness Act and the Fight to Protect Miners Ridge and the Public Interest.”

“Every side sees itself reaching toward public interest. Kennecott’s argument was weaker,” Sowards said. “This campaign was a test for everyone involved.”

Most significantly, it was the first test of a mining provision of the Wilderness Act passed in 1964. The law allowed prospecting in designated areas to continue for 20 years. But the will of the people overcame that power.

Sowards wrote that “the mining exception made what happened at Miners Ridge important, controversial, and, above all, historic.”

Could that open pit have been seen from the moon? The question gets an answer, of sorts, in Sowards’ introduction, titled “The Telescope.”

It was Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club in the late 1960s, who had likened the copper operation he was fighting to a man-made crater “so large it would be visible from the moon.” The author McPhee countered that the claim was exaggerated.

Sowards’ book notes that the Sierra Club chief “admitted that seeing the mine from the moon would require ‘a small telescope.’”

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460; jmuhlstein@heraldnet.com.

The book

Adam Sowers’ new book, “An Open Pit Visible from the Moon,” is available on Amazon and at the University of Oklahoma Press: oupress.com/books/15458872/an-open-pit-visible-from-the-moon