MALTBY — Dragonflies buzzed around a cool, slow-moving stream Wednesday in the lower Little Bear Creek watershed.

Not too long ago, it was a farm with cattle. The stream did not flow properly and the wetland muck was filled with dirt and rock. Snohomish County spent a little over $4 million to turn the run-down farm off 58th Avenue SE into protected land — 17 acres in total.

Springs feed two newly revitalized streams on the property. Those flow into nearby Little Bear Creek, which then feeds into the Sammamish River.

There have been sightings of bobcats, coyotes, deer and huge numbers of birds, said Darla Boyer, a senior environmental planner from the county’s public works department. Edmonds College set up wildlife cameras on the property.

“They got a red-tailed hawk capturing a rabbit and we actually caught it in action,” Boyer said.

The group also said they got a three-photo set of two young coyotes spooking a deer and her fawn, causing them to run off. The county also planted 21,000 trees and shrubs.

A combination of compost and wood-chip mulch helped rejuvenate the soil. It was still fresh and crunched underfoot as groups toured the property Wednesday, trying to avoid disrupting the young foliage. A wasp nest hung off one young tree. Small pink flags marked a safe path through the swampy ground.

Rebuilding a small corner piece of the river basin included tearing down 17 buildings, ripping up huge pipes and scraping feet of soil off what was once wetland.

County officials said the mitigation could save taxpayers more than $30 million on future road projects through various environmental credits.

“Vital to our future is the quality of our environment here in Snohomish County, and if we don’t do projects like this as we grow, we will lose it,” County Executive Dave Somers, who has a master’s degree in forest ecology, said Wednesday during a ribbon-cutting on the property. “Seeing a place like this that has been restored after so many years … I’m very, very excited to see this.”

Nearly every department in the county contributed in some fashion to the project, Boyer said.

Prior to Snohomish County buying the property in 2017 for $755,000, the land’s primary use was agricultural, used to raise cattle and birds. Another $3 million or so was spent on mitigation.

At the time, the site was a mess, littered with rusty, junked cars. Birds, with wings clipped, had been kept in cages and ponds throughout the property. The prior owners had made extensive changes to the wetlands. The land had been cleared, filled, drained and developed. Parts were also over-grazed.

Historic satellite photos show the deterioration of the land from 1990 to 2017 as trees disappeared. Thousands of feet of fence — and basically anything else manmade — were removed by the county.

In one surprise, workers found giant drainage pipes. Cleanup was originally estimated to cost $1.2 million, but the project ballooned both due to these surprises and inflation following the pandemic.

“There were a lot of unknowns,” Boyer said.

Despite the unexpected costs, it’ll still be a boon for the county.

When new roads are built, local, state and federal laws often require those projects to provide some sort of environmental offset. Basically, if you lay down some blacktop, you might have to plant some trees, too.

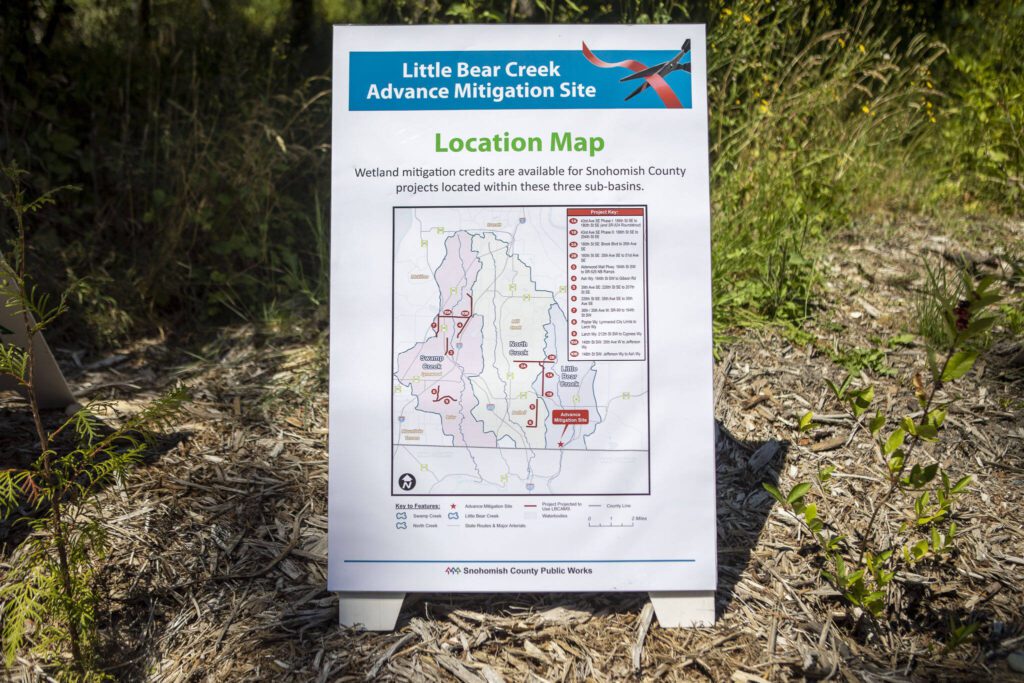

However, cleanups like the Little Bear Creek mitigation create credits the county can use for other projects in the future.

Environmental Science Associates, which consulted with the county on the project, said it would generate over 100 of these regulatory credits, which would offset construction costs to projects throughout the county. Those will include planned projects to Alderwood Mall Parkway and along 43rd Avenue SE, among other places, according to the county.

County officials say the project will “save millions of dollars on future unavoidable wetland mitigation costs incurred to meet regulatory requirements.”

In essence, it was a strategic purchase.

“This project, to me, is an example of Public Works doing work better for the environment and better at lower cost,” said Steve Dickson, the county’s transportation and environmental services director.

The entire site is now “protected in perpetuity,” a county press release said.

Completion of the project required 14 permits from five agencies over a period of four years, beginning in December 2018. The Tulalip, Stillaguamish and Muckleshoot tribes were part of the project, as were federal, state and local agencies. The county also used consultants from Environmental Science Associates.

County public works staff will monitor the site over the next 10 years to make sure vegetation is growing as it should and new habitat is actually working.

Jordan Hansen: 425-339-3046; jordan.hansen@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @jordyhansen.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.