SNOHOMISH — As the clock neared 10 p.m., Snohomish City Council members listened to an ever-so familiar voice.

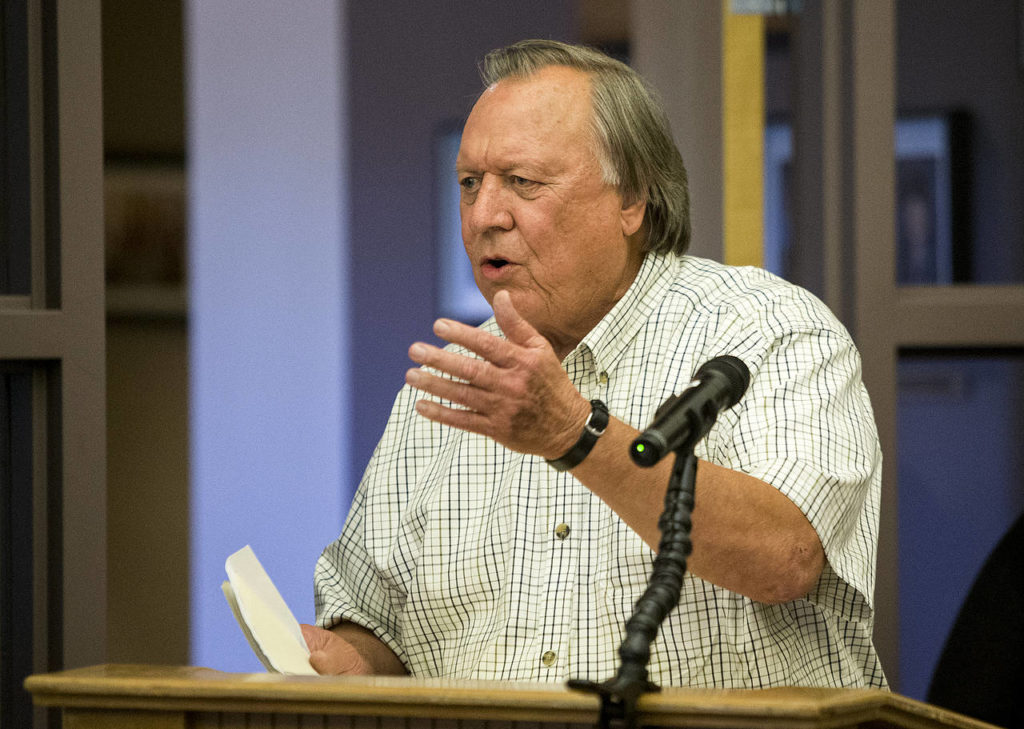

Morgan Davis, 75, stood behind a lectern for the seventh time that December night. He was testifying on every item on the council’s agenda. He talked about how the city should fight crime and allocate its money.

He is a chronic critic.

Davis, a Boeing Co. retiree, owns an apartment building in Snohomish, but lives about six miles outside of town. He said he is looking out for his tenants’ interests.

The council is his hobby, Davis said. He spends a half hour handwriting comments before every meeting. He reads from yellow pages ripped from a legal pad.

Bill Betten, 59, testified six times that same night. His home is 300 feet outside city limits.

“It’s very hard to get people engaged,” Betten said. ‘They won’t step up and be a voice, so I have to be two peoples’ voices and I may have to speak louder.”

Vocal critics

More then 9,000 people live in Snohomish, which was named after a local Native American tribe. The town takes pride in its history, which dates back to 1890 when it was first incorporated.

A couple of the city’s most vocal critics don’t live in town and can’t vote on issues. For some, calling Snohomish their home is less about city boundaries and more about the high school they attended.

Davis graduated from Snohomish High School. His grandfather, who fought in the Civil War, homesteaded a property near Thomas Lake, which is now part of Mill Creek. Back then, the house had a Snohomish address.

“They very much see Snohomish as their hometown,” Councilwoman Lynn Schilaty said. “But the reality is, they are not voters. It’s always a dilemma for a council member to respect the community at large, but our responsibility is to our constituents foremost.”

The council sets a three-minute timer with a buzzer to keep comments brief. If that doesn’t work, the mayor bangs a gavel on the desk.

A consultant was hired in 2015 to boost community engagement and government transparency. She worked with an open-government committee of nine people from the community who provided recommendations, such as a revamp of the city’s website and additional public forums.

She was paid $12,090 for the seven-month project, City Manager Larry Bauman said. At the end of this year, the city plans to evaluate its outreach efforts.

So far, City Council meetings seem dominated by critics focused on catching Snohomish leaders in mistakes.

“These gotchas get old after awhile,” Schilaty said. “If we made a mistake, point it out. We’ll rectify it.”

Schilaty has served on the council for nearly 10 years. Davis has sat in on meetings for as long as she can remember.

Betten, a newcomer to council meetings, said the city lacks transparency.

Others in the past have thought so, too.

Rocky history

In 2012, the city attorney sent letters to more than a dozen homeowners informing them they had two weeks to pay outstanding fees — ranging from $3,000 to $20,000 — connected to the purchase of their houses.

The city had failed to collect fees from the developer who built the homes, a requirement before any final building permits can be issued.

Bauman and other city officials had known about the unpaid debt since 2008, before some of the new homes were sold.

Bauman told homeowners the city was legally obligated to collect the fees from the current property owners. His hands were tied.

People called for the fees to be dropped and Bauman to be fired.

A criminal investigation uncovered a city inspection document for a home with no outstanding fees that appeared to be forged. Records also showed the city did not disclose the fees to title companies.

The council unanimously voted to waive the fees.

Now, Betten and others are working to weaken the city manager’s role.

For decades, the city operated under a council-manager form of government. The council appoints one of its own to serve as mayor while a city manager handles the day-to-day operations. Last fall, Betten introduced Proposition 2, a bid to replace that structure with one led by an elected strong mayor.

He couldn’t vote for his own ballot measure.

It passed by nine votes in November. Schilaty wondered whether people understood what the change in government entailed. There were 4,445 votes cast, but more than 400 people opted not to vote on Prop. 2. A recount confirmed the city’s future transition in governance. A new mayor is expected to take office after the general election in November.

Lots of talking

Proposition backers argued the change would save money. Depending on who is elected into office, it may prove more expensive.

“They’ve never been able to articulate their long-term vision and how it’s going to be better through the form of government that’s now going to take place,” Schilaty said.

Betten and proposition supporters have dominated public testimony, especially around the time of the November 2016 election. Davis spoke 18 times in the span of four meetings, amounting to about 54 minutes. Betten spoke 11 times.

Councilwoman Karen Guzak introduced the three-minute timer when she was mayor as a way of trying to make sure more people would have the chance to testify. Instead, Davis has just opted to speak more often, she said.

“A lot of times, I don’t get enough time,” Davis said. “They cut me off.”

During a May meeting, a woman was telling the council about a noise problem in her neighborhood when Davis shouted a comment from the back of the room.

“Thank you for your silence, Mr. Davis,” Mayor Tom Hamilton said.

Davis said his criticism is constructive.

Guzak served as mayor for seven years before stepping down in February. Early on, she invited Davis to address his concerns. She called their discussions “fruitless.”

“He enjoys criticizing us,” Guzak said. “If we were to run the city as Morgan Davis wants to, I think we would have an impoverished and dysfunctional city.”

Geoffrey Thomas, mayor of Monroe, said people living outside of his city sometimes attend council meetings.

However, “I’ve never had to gavel somebody down,” he said.

If someone reaches the time limit for public comment, Thomas said he politely asks the speaker to wrap up. For the most part, that works.

Everett City Council President Judy Tuohy said some people attend weekly meetings simply to grouse. One person drives in from Lynnwood.

Demanding answers

Schilaty has noticed a difference in the type of comments in Snohomish as of late.

There are more questions for city staff.

“Public comment is an incredibly important part of the public process. It’s something I value very much,” Schilaty said. “But this idea that it should be interactive is, I don’t think it’s productive or a direction I would like the council to go down.”

Davis and Betten have asked the council for answers on the spot. Outside of meetings, Hamilton and other government officials are peppered with emails. Betten has sent text messages to the deputy city manager at 8 p.m. on a Friday. He and others once went knocking on Hamilton’s door, demanding to talk about the timing of the mayoral election.

Most recently, Betten is concerned about Snohomish’s Carnegie building. It was built in 1910 and served as a library until 2003 when a new library opened. Plans were made to convert the Carnegie building into an education center.

The project entails removing an annex that was added to the front of the building in 1968. A leak in its roof caused the property to be closed as a safety precaution. Betten thinks the drippy roof will be used as an excuse to demolish the annex, so he formed the “105 Cedar Avenue Foundation” in hopes of preserving it.

During a May council meeting, Betten read from Washington’s Open Public Meetings Act. He alleged that former City Council members had made a decision years ago to remove a deed that required the building to be used as a library. He said the decision was not discussed openly.

“I’m going to keep reading this every two weeks until you understand,” Betten told the council.

Hamilton provided Betten with minutes from public meetings in 1994 and 1995 when the council directed staff to remove the deed restriction, giving the city latitude in terms of how the library property could be used.

A new law that takes effect next month requires local governments to host a public hearing prior to removing any covenants associated with city-owned property.

The Snohomish Carnegie Foundation has been drafting plans for the education center at the former library for years.

Anarchy or democracy?

There is a “history of these folks coming in with their negative viewpoint and trying to undo the work of so many community groups and foundations without thought to the bigger picture — what our community needs,” Guzak said.

The message is one of “anarchy,” rather than democracy, she said.

“This is my opinion, that they’re actually abusive of the council and the council’s decisions,” Guzak said.

Last year, John Kartak, who lives in town and is now running for mayor, attempted to seek an injunction to block the council from voting on a mayoral election date. Kartak wrote the petition himself. He thought the council was moving too quickly.

“When something is voted in, there is an expectation that it will be implemented in a timely manner. We need to move forward,” Schilaty said in a December meeting.

A hearing was scheduled for the same day the council planned to vote. The judge threw out Kartak’s request because the paperwork targeted the Snohomish County auditor instead of the City Council.

In July, Betten attempted to recall Guzak from office when she was still mayor. The paperwork he filed with the county auditor listed an address for Betten inside the city. Anyone who files a petition to recall a public official must be a resident where that official serves.

Within three weeks, Betten withdrew the petition, alleging his family had been harassed.

He filed another petition in August to alter the language in the voters pamphlet explaining Prop. 2. This time, his home address outside the city was listed. The petition was denied.

Prop. 2 supporters have criticized Bauman for living in north King County.

Davis demanded an investigation into a former city councilman who had moved outside of Snohomish last year. Zachary Wilde resigned in December. He moved to take care of his parents who were dealing with health problems. Wilde returned more than $4,000 he had earned during his time on council and submitted a written apology.

Davis called it fraud.

Schilaty said the city’s critics have a tendency to hover around the same issues, which often resurface every two weeks in council meetings. She hopes people will focus on positive efforts to move the city forward.

Candidates have filed for the city’s strong mayor position and five council seats. Guzak, Kartak, Councilman Derrick Burke and Elizabeth Larsen are running for mayor in the August primary.

Caitlin Tompkins: 425-339-3192; ctompkins@heraldnet.com

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.