EVERETT — The worsening fentanyl crisis, the allocation of the state’s $518 million opioid settlement and a family tragedy are converging catalysts for Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers’ new “holistic plan” to address the drug crisis.

Somers was scheduled to announce the two-pronged approach Thursday morning.

First, it proposes a spending plan for the initial $1.4 million slice of opioid settlement funds Snohomish County will receive.

Second, it issues an executive directive to the county Department of Emergency Management to coordinate the response to the crisis through the Multi-Agency Coordination group. The group was created in 2017 as a collaboration between the Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office, the county health district and human services providers.

From 2017 to 2022, the number of opioid-related overdose deaths reported in Snohomish County more than doubled. Somers said the stressors of COVID, the rising cost of housing and the “tidal wave” of cheap, strong, inexpensive drugs have exacerbated the crisis.

Last year, Snohomish County lost more than five people per week to fatal overdoses from opioids. So far this year, 82 people have died.

“In King County, two people die every day (due to fentanyl), and my brother was one of them,” Somers said. In March, Somers lost his younger brother, Alan Paulsen, to a fentanyl-related overdose.

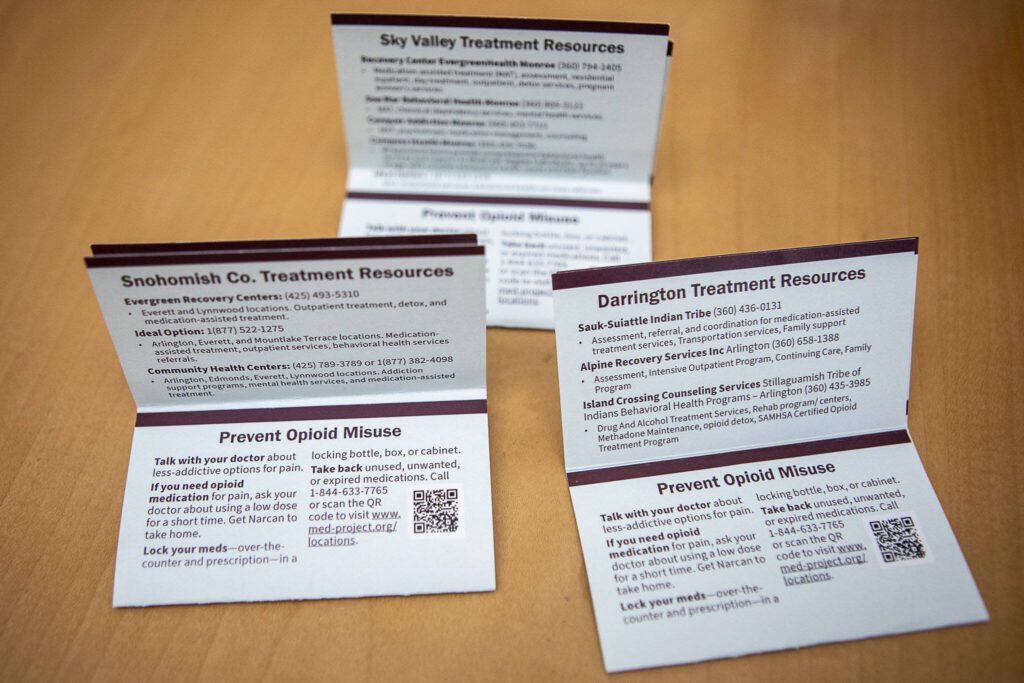

Last fall, the state received a $518 million opioid settlement from three pharmaceutical companies. Snohomish County is set to receive $14 million. The funds will be doled out over the next 15 years, and Somers’ spending plan addresses the first $1.4 million.

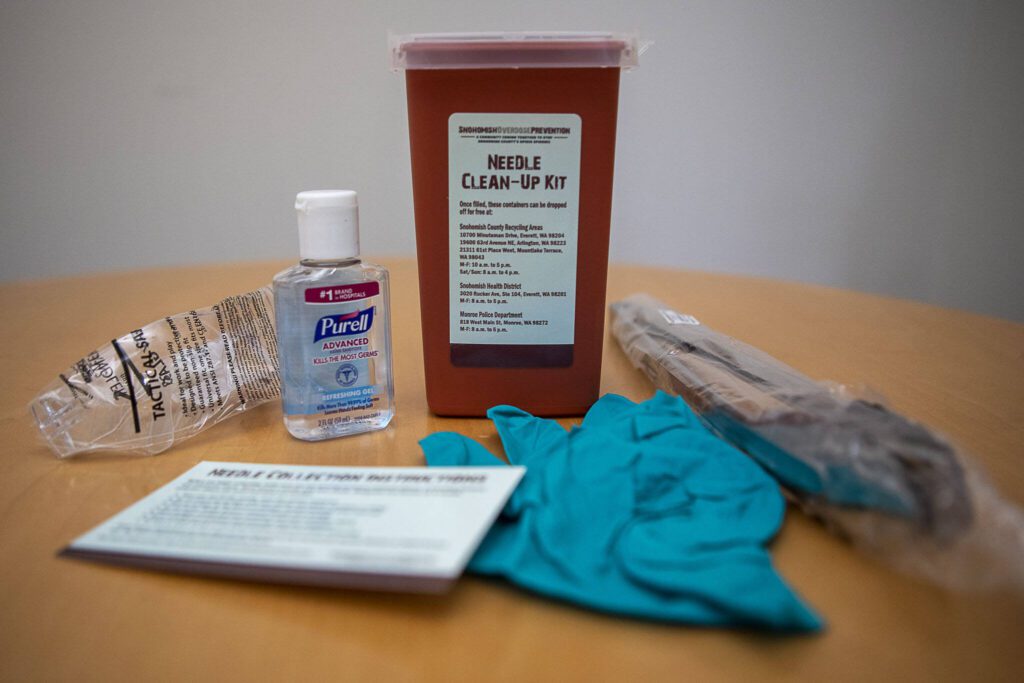

If approved by the County Council, the plan would expand the county’s first responder Leave-Behind Program by making naloxone, commonly referred to by the brand name Narcan, more readily available to fire and emergency medical services. It would also offer funding to organizations that wish to expand their grassroots opioid-related efforts. And it would increase school education efforts to fight substance use disorder.

The money will also help with data collection to quantify the drug crisis.

“To understand the problem — to really attack it and address it — we need to know what drugs are coming in, what we’re dealing with, the people who are affected by it, what their needs are, where they come from, what’s driving (increased drug use),” Somers said. “So data is really important. Public health is built on data … and this is a public health issue.”

The executive’s directive also outlines an aggressive timeline for the MAC group and establishes a Disaster Policy Group, consisting of Somers and the heads of relevant agencies, to hold MAC accountable.

Starting Thursday, the MAC group has 30 days to submit updated goals to the Disaster Policy Group and 90 days after that to submit short-term strategies to address drug-related deaths, public safety and property damage concerns. The group then has another 90 days to submit long-term strategies to deal with the larger issue of addiction.

On Tuesday, the state Legislature passed a bill making drug possession a gross misdemeanor, while allocating millions of dollars toward treatment efforts and support resources. The law replaces a 2021 law set to expire in July.

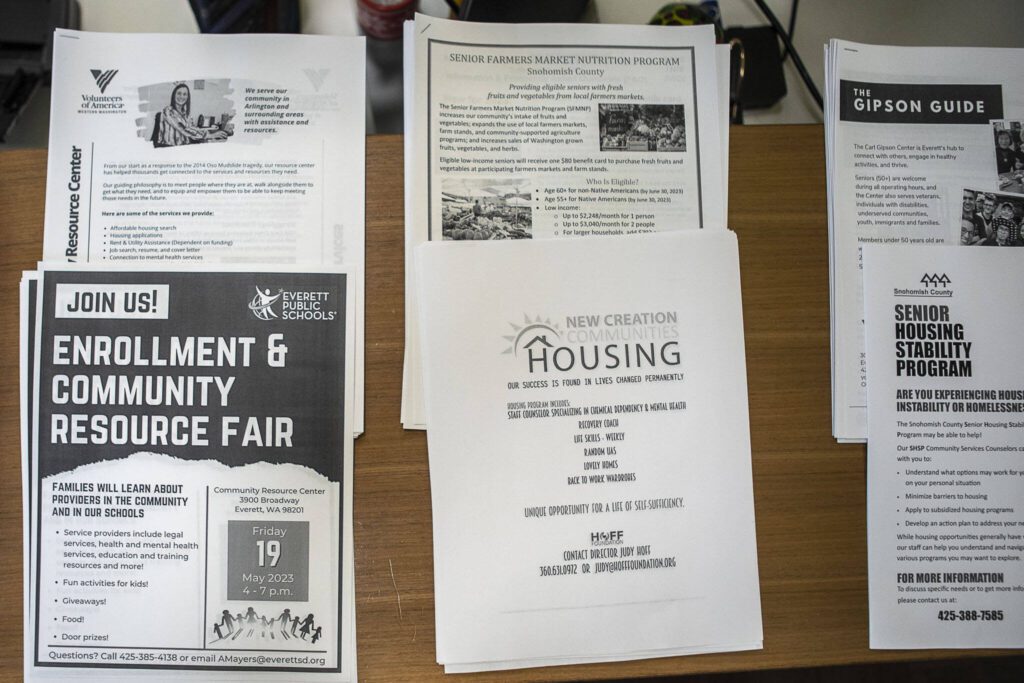

Kelsey Nyland, spokesperson for the county’s Office of Recovery and Resilience, explained the goal is to create an “ecosystem” of resources to help support those in the throes of the drug crisis. The county has money to allocate and systems in place — now they aim to create an intertwined web of support.

For example, the Carnegie Resource Center, located just off the county campus on Oakes Avenue in Everett, is a one-stop hub for an array of resources, such as health care enrollment, housing options, legal clinics and educational training. It also offers a free eyeglasses program, phone and Wi-Fi access.

Rebecca Nelson, the director for the Carnegie center, said the center served 502 people in person in April alone.

“On Mondays and Tuesdays when we have the free government phones and the free tablets, it’s standing room only,” Nelson said. “When we come in at 9 a.m., there’s usually a line out the door we get here.”

Just around the corner, the Diversion Center is a 44-bed facility that offers “short-term placement and shelter to homeless adults with a substance use disorder and other behavioral health issues.”

The goal is to divert community members away from incarceration and toward treatment. Most stay for an average of 12 days.

“Frankly, we need to meet people where they are,” Somers said. “If they’re homeless, and they’re out on the streets, we’ve got to go meet them where they are. We’ve got to have the teams to go out there and say, ‘Look, we can offer you services, and we can really help you.’”

Kayla J. Dunn: 425-339-3449; kayla.dunn@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @KaylaJ_Dunn.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.