A bucket of gloves, rows of rakes and wheelbarrows ready to roll. And mounds and mounds of good earth waiting to be sifted, sorted and shoveled.

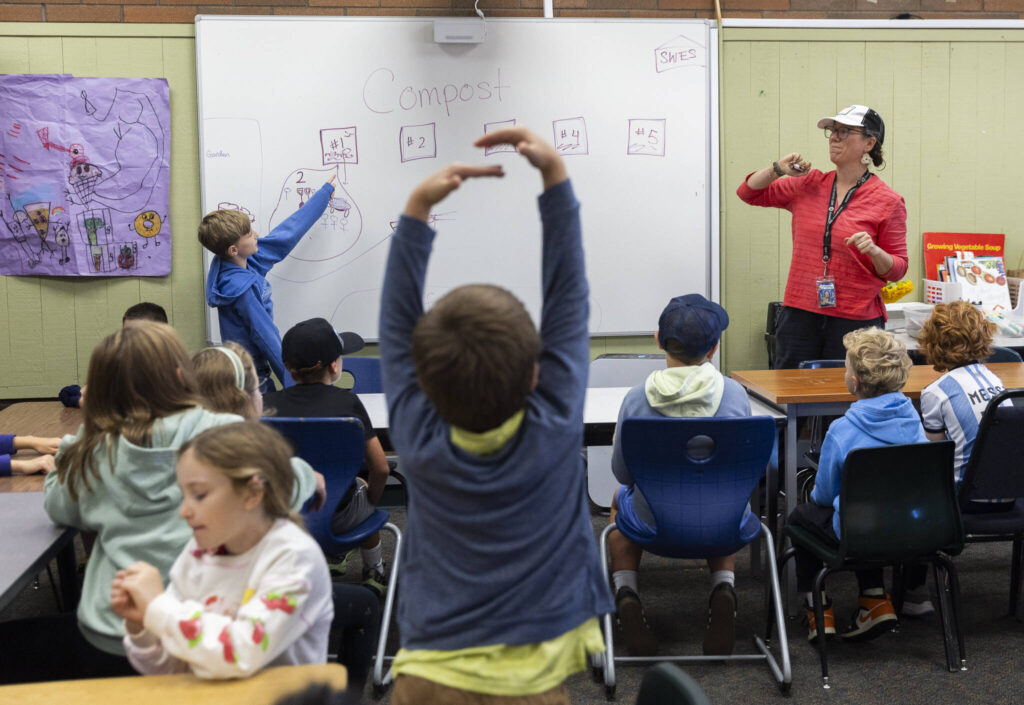

It’s time for third graders to dig into composting, one of many hands-on lessons of the South Whidbey School District Farm Program. A combined agricultural and culinary program, it teaches the basics of real food and where it really comes from — the soil, the fields and the farmers. Some of the pickings even end up on their cafeteria plates.

Under the sun as they sift through dirt, a variety of comments and questions ring out from the sprout-size students:

“Look, a real potato root!”

“Why do we put eggshells in this?”

“I found a wormy.”

“This is a giantatumous amount of dirt. This is the mother lode.”

For more than a decade, planting, harvesting, seeding and weeding, and of course, noshing on an array of vegetables, fruits, — even flowers — have provided farm-to-table learning for grades K-12. Fundraisers, equipment donations, non-profit organizational grants, fiscal partners, farm partnerships and visits from chefs keep the program going and growing, said Jay Freundlich, program specialist who led the elementary farm curriculum for five years.

More than $100,000 has been donated to the program over the past decade from the community, he added.

Deep Harvest Farm, that grows hundreds of certified organic seeds on Whidbey Island, has been integral in helping many of school crops take root.

“We grow enough to call it a farm. It’s not just a small patch of a garden like some schools,” explained Freundlich, who is assisting his replacement, elementary school farm teacher Amy Hadlock, before retiring this fall.

“The program was created so students have to do meaningful work to learn where their food comes from.”

Three sprawling plots add up to about 2 acres. They are situated behind the elementary school and at the nearby combined middle-high school campus. The district’s budget covers the program’s costs and staff, which includes a farm manager, elementary school teacher and para-educator, high school teacher and AmeriCorps volunteer. During the summer, seven high school interns assist with planting, weeding, watering, harvesting and running the farm stand that opened in front of the high school several years ago.

The science of farming is emphasized for middle and high schoolers through lessons in biology, the environment and the business of agriculture, said farm manager Brian Kenney.

Rows upon colorful rows of cucumbers, kale, bok choy, peppers, radishes, lettuce, tomatoes, squash and many other veggies and flowers thrive in front of South Whidbey High School, home of the Falcons. Behind it, sunflowers tower from the back garden that includes greenhouses where micro greens sprout. Pointing to the sky-high yellow plants soaring above the soccer and football fields, Kenney says, “Sunflowers, those are really popular sellers at the farm stand.”

Another fall delight — pumpkin pies — made from the orange orbs fifth-graders have grown and sown — will soon be whipped up in school then proudly taken home to share. Now that’s a homework assignment!

A leader in cultivating lessons of soil and sea

In 2014, South Whidbey School District was the first district in the nation to pair with food management company Chartwells to adopt its School Garden protocols, bringing produce from the school yard into the cafeteria kitchen. Since then, dozens of other school districts have enrolled in similar partnerships. Produce from the school farmalso helps the nonprofit Whidbey Island Nourishes provide meals for low-income families.

Last year, Washington state named South Whidbey a STEM Lighthouse School for its “Farm, Forest and Sea” program that links with numerous local organizations; Sound Water Stewards, Whidbey Camano Land Trust, Maxwelton Organic Farm School and Whidbey Watershed Stewards to teach about environmental connections and stewardship.

The tiny district of 1,100 students has always embraced its iconic Northwestern tableau of woods, water, farms, fields and diverse wildlife, said South Whidbey Elementary School Principal Susie Richards.

“We teach science and math and art through the acres of forests surrounding us, the Salish Sea, local farms and through our own farm program,” she said. Recalling her days as a teacher in the 1990s, Richards added, “It’s been a beautiful progression to watch over the years. Some of my former students have come back to raise their own children here because they want them to have that same connection.”

From garden nibbles to culinary know-how

Lessons progress as students age, starting with strolls and tastes through rows of carrots, lettuce, tomatoes, corns and kale, pumpkins, squash, flowers and towers of scarlet runner beans, sweet peas, and edible flowers growing behind the elementary school.

What’s known as ‘nibble time’ follows every lower-grade lesson, whether it’s taking place outside or inside. Pick a carrot, wash it off, feel that crunch. Surprise! It looks and tastes nothing like those wimpy weird carrots-in-a-bag from the supermarket.

Sitting down for a little pesto paste on a tortilla chip topped with a tiny tomato makes up another snack. It takes place just after learning how to chop, mix, and mash basil, garlic, olive oil and sunflower seeds into the yummy green sauce. Nibble time also includes lessons in hospitality, thankfulness, cleaning up and the lost art of breaking bread (or chips, kale, celery) together.

Sometimes, kids get to “free range” the rows, picking whatever pleases their palate.

“Believe or not, their favorite garden veggie to nibble is sour leaf,” Hadlock said, known as “Farmer Kate” to her young charges.

“They just love it. I have to control how much they eat.”

Really?

Camden Dilley, 8, was asked to name his favorite veggie as he left Hadlock’s class.

“Sour leaf,” he replied.

(Sour leaf, for those not schooled at South Whidbey Farm Program is a lemony leaf that packs a tang. Also known as French sorrel, it’s often found in fancy restaurant salads.)

Unprompted, Dilley also offers an A-plus accolade: “One of my friends was jealous we have a garden program,” he said. “There’s nothing like it at his school.”

Every grade level has a theme. Fourth graders learn all about different animals deep in the dirt and buzzing in the air: earthworms, beetles, voles, pollinators, birds of prey.

“The earthworm being the most important, of course,” said paraeducator Kate Miller, who assists Hadlock during the whirlwind 45-minute classes. “There is a bee hive that they study. They even learn animal husbandry when we hatch chicken eggs in an incubator.”

Fifth graders take to the kitchen. The culinary classroom is formed into a large square of stainless steel commercial countertops.

Standing over the counters, students learn the finer points of making pesto, pasta, pies, apple sauce and more.

A whiteboard lists the day’s recipe with step-by-step instructions.

Shelves stocked with an impressive inventory of blenders, food processors, measuring cups, spoons, spatulas, rolling pins, spinners, slicers, dicers, muffin tins, pots, pans and utensils for every utility line the walls.

A banner sign, CAFE: Culinary Arts and Farm Education, sums up what’s up in this classroom.

Parker Whetstone, 11, said his pesto class taught him about allergies and food substitutions.

“One student was allergic to basil, so we used kale,” he said, “which, in my opinion, tasted better.”

Whetstone said he’s eager to try his new skills at home. “I just recently made scrambled eggs from scratch — not using that liquid stuff,” he said. “I used pepper and put cheese on top. It was really good.”

Patricia Guthrie is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Daily Herald

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.