‘Got Mud?’ Researchers monitor the health of the Puget Sound

Published 1:30 am Thursday, May 8, 2025

EVERETT — Holding a hard hat decorated with a “Got Mud?” sticker, Sandy Weakland hopped on her crew’s boat. Her shimmering eye shadow contrasted her black waders and rubber boots, but the sparkly makeup matched the morning sun reflecting off Puget Sound.

Weakland is a sediment monitoring lead for Washington’s Department of Ecology. For the next few weeks, she and other state researchers will make their rounds across Puget Sound, Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay.

The team’s data informs the state about ecological changes and can be a helpful indicator of whether or not regulatory policies are effective in curbing pollution.

This year, in addition to collecting sediment and water samples, the team is collecting tissue samples of benthic invertebrates — organisms without backbones living under the Sound’s floor.

“Sediment monitoring offers valuable clues about both natural and human-influenced changes in the Puget Sound basin,” Weakland said.

Tissue samples will help researchers track toxins in the food chain, lead taxonomist Dany Burgess said, filling in the missing link between pollutants and how they affect larger, more well-known Puget Sound species like salmon and orcas.

Every year, the researchers survey 50 spots, some of which have been monitored since 1989. When the boat reaches a site, the researchers drop equipment down to the Sound floor, scooping a chunk of sediment and whatever is living in it and raising it back to the surface.

As some team members pour mud into vials and plastic baggies on the boat deck, others sit inside on benches, picking through the sediment to pull out organisms.

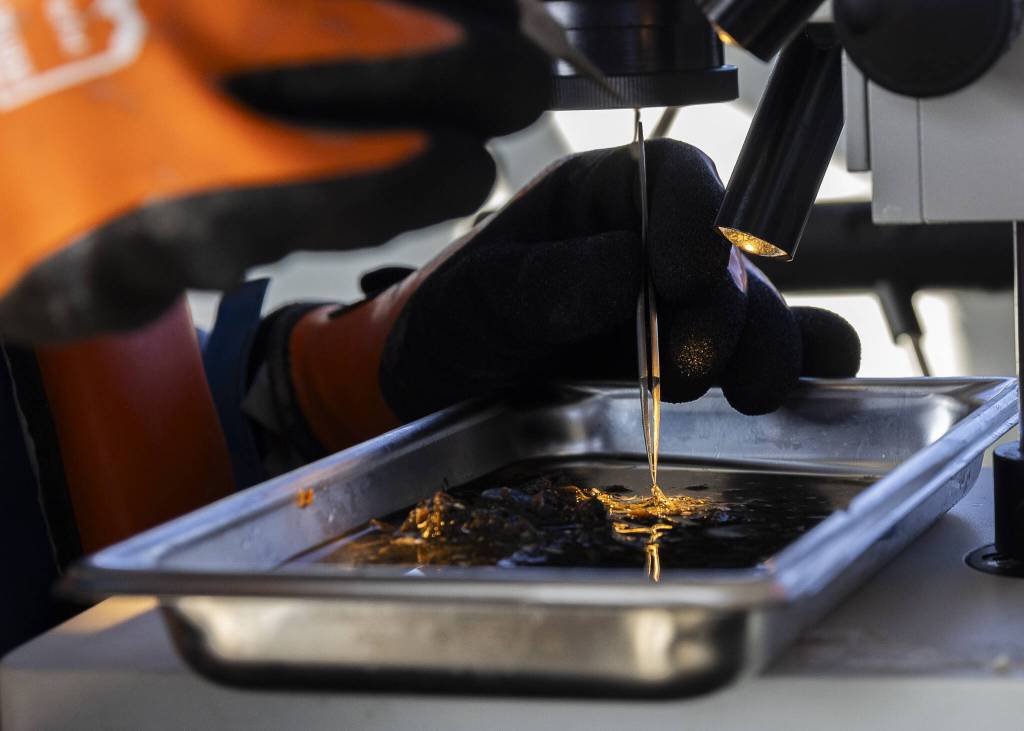

Burgess methodically moves her tweezers through a tray of mud, her body swaying with the waves as she peers through the lens of a microscope. Her job as the lead taxonomist is often to take count of the species the team finds, tracking what species are found where and in what abundance.

Many of the organisms she plucks from the tray are smaller than a pinky nail and, under the light of a microscope, look like miniature aliens. Worms wriggle, and baby clams push themselves around with tiny feet.

The group needs 20 grams of tissue for each site, so it’s a tedious process to sift through the mud samples to get enough organisms to collect data for one site. But Burgess said she loves her job and, even through the repetition, she learns something new every day.

“I feel like what I’m doing is contributing to the greater good somehow,” she said. “It’s contributing to the bigger body of knowledge that ultimately will be helpful for environmental protection.”

At the site just outside Everett’s port, the benthic communities have remained relatively stable through the decades of monitoring, Weakland said, and the chemical condition of the site has improved slightly over time.

“There’s all kinds of work being done around the Sound to clean up legacy containments,” Weakland said, referencing cleanup projects in Port Gardner Bay. “I think we are seeing some of that improvement.”

But some inlets are getting worse, affected by higher temperatures, lower dissolved oxygen levels and changes in currents, she added. Even varying snow levels in the mountains and inland developments can alter conditions in the Sound.

“I’m sure everybody can see that there’s more things being built everywhere, so the landscape [is changing],” she said. “It’s all connected. It always leads to more questions.”

A previous version of the story contained incorrect spellings of two Department of Ecology researchers. The correct spellings are Dany Burgess and Emma LeValley.

Eliza Aronson: 425-339-3434; eliza.aronson@heraldnet.com; X: @ElizaAronson.

Eliza’s stories are supported by the Herald’s Environmental and Climate Reporting Fund.