MONROE — When Jay Wellan felt the magnitude 4.6 earthquake just before 3 a.m. Friday he wondered, for an instant, if this was “the big one.”

His house, just south of the quake’s epicenter in Monroe, seemed to move in every direction at the same time.

The thought passed as the shaking diminished.

“Seconds in an earthquake seem like hours,” Wellan said. “But this one was fairly quick.”

Thousands of other Puget Sound-area residents were shaken awake early Friday as twin earthquakes hit the region, minutes apart and both centered under Monroe, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The first quake, magnitude 4.6 and 13½ miles deep, hit at 2:51 a.m. A second one two minutes later was magnitude 3.5 and 18 miles deep. The first of at least five aftershocks followed at 2:56 a.m. Over the next couple of hours, they ranged from 0.9 to 1.7.

This wasn’t Wellan’s first time feeling a quake close to home.

He recalled a 1996, magnitude 5.3 shake that originated near Duvall. That one seemed to last a lot longer, he said.

But an earthquake’s magnitude doesn’t indicate how intense it actually feels. Brian Terbush, an earthquake and volcano program coordinator with the state emergency management division, said magnitude is the total energy release, but intensity is what you experience.

An earthquake has one magnitude, but many different intensities depending on a person’s distance from the epicenter and what kind of ground they’re on.

Terbush compared it to a light bulb. While it has one voltage, it will seem brighter up close than across the room. Or, if you’re looking in a mirror or through a screen, it may seem brighter or dimmer.

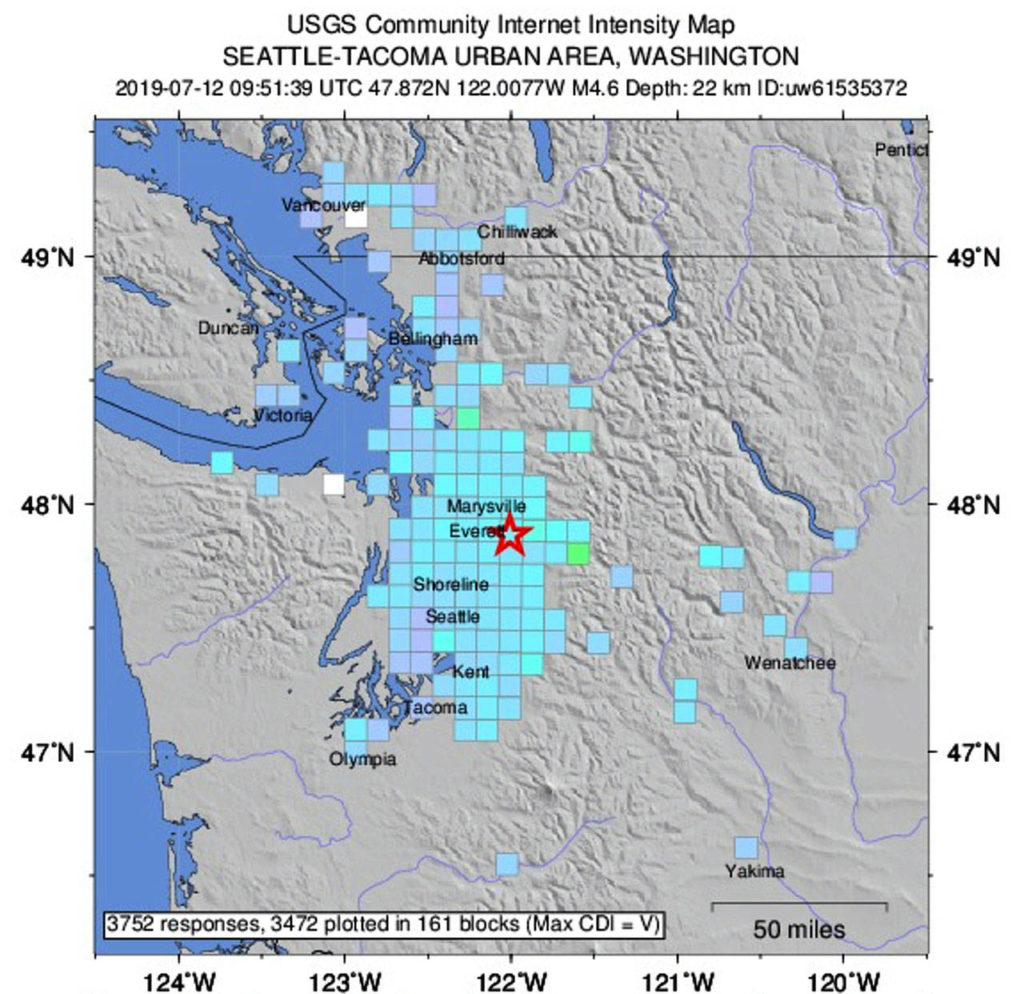

The U.S. Geological Survey ranks the intensity of an earthquake on a scale of one to 10 based on feedback from those in the area. By 3 p.m. Friday, 14,000 people across Puget Sound had reported Friday’s earthquake as ranking between a 4 and 5, considered light to moderate shaking.

That’s the same intensity that those in Los Angeles reported after a magnitude 7.1 earthquake rattled Southern California last week.

The Snohomish County Sheriff’s Office and other government agencies said there were no reports of damage, and the quakes did not pose a tsunami threat, according to a tweet by the U.S. National Tsunami Warning Center. The Snohomish County Public Utility District reported that some customers in the area lost power due to a tree falling on a line but tweeted that it was “difficult for us to say if it was directly related to the quake.” Electricity was restored within a few hours.

The shaking awakened people as far away as Seattle. A USGS intensity map suggested the earthquakes could be felt as far south as Olympia and as far north as Vancouver, British Columbia.

In an email, Mukilteo resident Don Holt described how it felt to him: “Awakened by low rumble. As I became awake, the house shook horizontally back and forth a couple of times, the quake being like a ripple on water, traveling through the ground. Eerie feeling — the shaking didn’t wake me, it was the sound. As the shaking stopped I could faintly hear the sound of the quake as the shock wave traveled on.”

The low rumble was also heard in Everett, where buildings shook side to side. The second tremor was softer and shorter.

Phil Mitchell, a retiree who lives in the View Ridge area of Everett, lost a few hours sleep.

“The sound woke us up first, then the house started shaking for about 15 seconds, then it kind of went away,” he said.

Minutes later he got a call from his daughter in Mill Creek asking, “Did you feel that? Did you feel that?”

Mitchell said Friday’s earthquake “wasn’t much compared to the one that hit Everett in the 1960s” when he was working at Scott Paper Co along the Everett waterfront.

“I saw the wave go right up and down the brick wall and everybody said ‘Earthquake’ and we all headed to the dock,” he said.

In Seattle, the quake could be felt as a gentle rocking.

The first quake originated 13 miles under the intersection of Fryelands Boulevard SE and U.S. 2 on the east side of Monroe, according to a USGS map.

The epicenter of the second was about a mile or so southwest of there, east of the city and focused 18 miles under the Old Snohomish-Monroe Road.

No initial reports of damage from this morning's shaking in @SnoCounty. A good reminder of the risk beneath our feet. These interactive maps and checklists can help you prepare. https://t.co/PrZeY6mVVs pic.twitter.com/nDp7sPPf6j— Snohomish County DEM (@SnoCo_DEM) July 12, 2019

Terbush said the U.S. Geological Survey is working to launch a mobile warning system that will alert people when a quake is heading their way. But before they launch it, he said the vast majority of people need to know what to do in an earthquake.

Based on a huge jump in 911 calls Friday morning, “we’re not ready for that,” Terbush said.

In Snohomish County, 911 call volume jumped up by more then 7½ times in the hour after the shake, according to emergency services.

“Mother Nature gave us a wake-up call this morning at 2:51 a.m.,” Snohomish County 911 Executive Director Kurt Mills said in an email. “We would be wise to listen to her.”

Smaller quakes like the ones Friday are not unusual in this area. And there have been bigger ones over the decades.

A 2012 Herald story reported that since 1900, six earthquakes of magnitude 5.0 or greater have been recorded as having caused damage in Snohomish and Island counties, or were centered within the counties’ borders.

Two significant faults run through Snohomish and Island counties. The South Whidbey Island Fault Zone consists of several intermittent faults that run from the Strait of Juan de Fuca southeast across Whidbey Island and south Snohomish County to Woodinville. The Devils Mountain Fault runs from the Strait of Juan de Fuca east near Deception Pass and across the Skagit-Snohomish county line southeast to Darrington.

Geologic evidence shows that large quakes have happened in the South Whidbey and Devils Mountain fault zones in the distant past. One happened in 1950 in the South Whidbey fault zone but data was inconclusive about the fault of origin, according to the University of Washington Seismology Lab.

Quakes on those faults carry a potential magnitude of 7.5, which could cause severe damage because of their proximity to the surface, according to a natural hazard report done for Snohomish County in 2010.

A possibly more serious threat is a quake in the Cascadia Subduction Zone 50 miles off the Pacific coast, which could inflict a quake of up to 9.5 in magnitude, causing catastrophic damage and capable of starting a tsunami.

Information from The Daily Herald’s archive is included in this story.

More online

• Pacific Northwest Seismic Network

• Washington Geological Survey

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.