Everett COVID survivor comes home, his sense of humor still intact

Published 1:30 am Sunday, December 26, 2021

EVERETT — Blink twice if you love me, Heather Columbus told her stepfather, as he clung to life in a hospital bed with a tracheotomy tube.

Gunard Hulskamp, 61, blinked just once — very deliberately, Columbus remembered.

She protested, laughing. He rolled his eyes.

“That was the big moment I knew he was coming back,” she recalled.

COVID-19 almost killed Hulskamp, who spent months intubated, on a ventilator, and suffered a collapsed lung that nearly left him brain dead. But his friends and family knew he would make it, they said, when he was back to his “smartass” self.

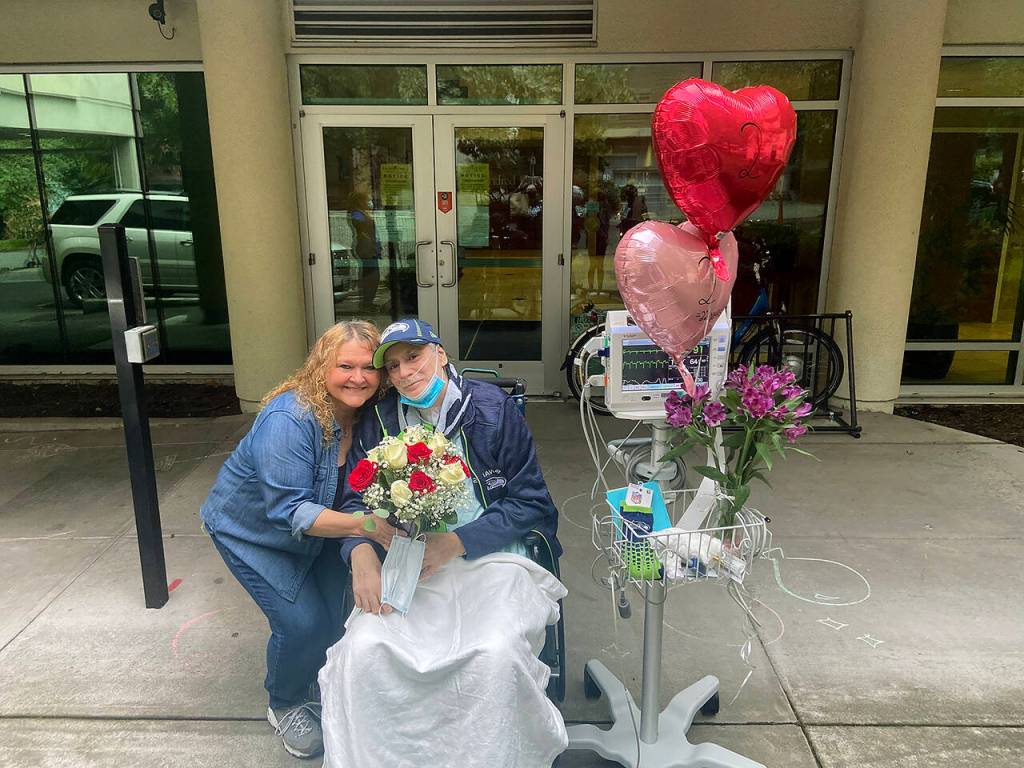

After 236 days at hospitals and in rehabilitation, where he learned to walk and talk again, they gathered Dec. 18 at Everett Center to see him take his first steps on his journey home.

They laughed, cried and cheered in celebration of a man who kept cracking jokes on what was nearly his deathbed.

They donned Seahawks hats and jerseys, in tribute to the die-hard fan who they now call their champion.

“You’re a warrior man!” one person shouted as Hulskamp rolled out on a wheelchair, then stood up.

“You’re going home, Dad,” Columbus told him as he inched toward his wife’s car, with the help of a walker.

Between his navy Seahawks beanie and his disposable mask, only his eyes and ashen eyebrows were visible. But his smile was easy to see.

That day, Hulskamp talked smack about the Dallas Cowboys. He quipped about finally having the freedom to “walk around in his skivvies.” He told relatives that, no, he would not start taking orders from his wife, Cheryl Hulskamp, even though he’ll need her help for many daily tasks as he returns to his regular life.

“You have to keep a sense of humor,” he said in an interview. “Without that, whaddaya got?”

The people around him called his homecoming a true Christmas miracle.

Ask Hulskamp if he feels like a miracle, and he’ll tell you:

“Hell yeah.”

‘Was that it?’

Hulskamp grew up in Everett. He met his wife when they were in kindergarten together at Longfellow School.

He has one child, plus three more of Cheryl’s that he calls his own, and a dozen grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Hulskamp caught the virus at a Woodinville manufacturer, where he worked the night shift using sheet metal to make mechanical parts, including some that power lifesaving ventilators.

Some of his co-workers got sick, too, but quickly recovered.

He tested positive for COVID-19 in April and was admitted into Providence Regional Medical Center Everett several days later, Cheryl said. She had been trying to schedule a vaccination appointment for him, she said, but appointments were scarce.

As his condition worsened and his oxygen levels dropped, Hulskamp became fearful that he would have to be intubated. He was scared he wouldn’t survive, or that if he did, he would rely on machines to breathe for the rest of his life.

He couldn’t speak for more than a few seconds, Columbus recalled. People who go on a ventilator don’t come back, he told her, crying.

Columbus, who’s 41 and lives in Marysville, had never seen him like that.

“You could see it in his eyes,” Columbus said. “He, I felt, lost hope at that time.”

One day in May, family members told him they loved him. Later, they got a message from the hospital: he had to be intubated.

His chance of survival was 50-50, a doctor told them.

Hospital staff told the family that there wasn’t much else they could do.

“We all just were kind of like, was that it?” Heather remembered. “Is that our goodbye?”

‘A fighter’

There were ups and downs.

In June, he started doing better — not great, but better, Cheryl recalled.

No longer needing the most intensive caliber of care at Providence hospital, he was transferred to Kindred Hospital in Seattle.

But then, staff at Kindred upped his ventilator settings because lung problems were making his breathing more difficult.

“He was telling me he was done,” Cheryl Hulskamp said. “And I kept on telling him, no, you have two great grandbabies. You have a family that loves you. I talked to him everyday.”

He was rushed to Virginia Mason Medical Center more than once.

Tubes were inserted into his lungs to drain fluid.

On June 29, one of his lungs collapsed for more than an hour, Cheryl said. An MRI and other tests confirmed he wasn’t brain dead. A doctor told Cheryl that, had he gone without oxygen another 10 minutes, he wouldn’t have come back, his wife recalled.

Even on the darkest parts of the journey, his family found unique ways to support him.

Before he was intubated, they surrounded him with posters decorated with printouts of encouraging comments from Facebook.

His nephew, who has connections with the Seahawks, got retired Super Bowl champion Cliff Avril to send him a video of encouragement.

“He still cries to this day watching that video,” she said. “That really lifted his spirits a lot.”

Keep fighting, his family told him.

He was in and out of consciousness. But he listened.

“He pulled through,” Cheryl said. “He really did. He’s a fighter.”

‘No machines’

On Oct. 12, his trach tube was removed.

The next day, he breathed on his own.

He was transferred to Everett Center a month later.

Hulskamp said he followed his wife’s voice.

“I think the happiest moment was when I breathed air,” Hulskamp recalled. “No machines.”

He has some memories from the intensive care unit, but they’re hard to describe, he said.

People called him a miracle. They stopped talking and stared when he managed to speak.

He remembers the people who helped him, too.

Jay Stone, a hospital security guard, read his lips and became his voice when he couldn’t talk.

Dulce Chavez, the Kindred nurse went above and beyond to connect him with his family, even during COVID-19 restrictions.

Chavez persuaded her supervisors to grant him 15 minutes with his wife on their 22nd anniversary on Oct. 16.

Beforehand, while the nurse helped him dress, Hulskamp asked her to send a picture to his wife of him in is hospital briefs.

“Even at his sickest moments, he would never lose his sense of humor,” said Chavez, who was at Everett Center for his recent release. “He would always crack me up.”

“He’s one of our positive stories,” she said. “I’m just happy he’s going home.”

‘Not everybody’

Each step is still a labor for Hulskamp. But he’s just happy to have working lungs and the doctor’s approval to drink Coca-Cola.

His wife is unsure if he will be able to return to his job.

Hulskamp didn’t seem too concerned about that on the day he came home, as he sat on the couch of his south Everett apartment with one of his two dogs on his lap.

“Now I just lay around,” he said.

“He’s definitely still a jokester. I’m glad he didn’t lose that,” Cheryl said. “He has a long way to go. He really does. But he already jumped the big hurdles.”

Hulskamp and his family want people to know that COVID is real.

“I wasn’t going to be vaccinated for a while, because I was scared. But once I saw my dad go through it, that changed my mind on getting the vaccination,” Columbus said. “It’s a personal preference, and I still feel that on certain levels — just because I know people have their reasons behind it. I’m not against that. But if you’re not going to be vaccinated, if you feel sick, where a mask. Protect your loved ones however you can.”

Having fought the disease himself, Hulskamp offers simple advice:

“Get vaccinated. Mask up,” he said.

“You don’t want to go to a hospital for that many days, I’ll tell you that. Not everybody gets through it.”

Rachel Riley: 425-339-3465; rriley@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @rachel_m_riley.