SNOHOMISH — At 9 years old, Anna Lomachenko watched from her home in Kyiv as protesters spilled into the central square during the Revolution of Dignity.

Protests began in 2013 after Russian-backed President Viktor Yanukovych chose closer ties to Russia over the European Union. The revolution culminated in a vote by Ukrainian Parliament to remove Yanukovych from office.

“One thing I remember in particular is that I can see all those events happening around me, but the thing is, I can’t influence them in any kind of way,” Lomachenko said. “What became my main goal is that when I grew up … I will have some tools … that if I have an issue that concerns me, I can do something about that issue.”

In 2018, Lomachenko’s family began moving to the United States.

“I thought we’ll stay in Ukraine longer but finally decided to move,” her mother Viktoria Thibault said. She and her daughters Anna, Eve and Inna joined her husband and daughter Olivia in Snohomish in 2019.

Now a senior at Snohomish High School, Lomachenko said art is her tool. It’s a tool to educate her peers about the war, to share the beauty of Ukrainian culture, and to draw a clear line between Ukrainian identity and that of an occupied people, she said.

“We have a totally different culture, different language, we have different traditions. We have different identity that I can talk a lot about,” Lomachenko said. “I want the world to recognize this difference between Russia and Ukraine.”

Lomachenko’s striking white headdress “Vinok” was selected from 260,000 submitted pieces as a National Gold Medal and American Visions Medal winner from the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards.

She found inspiration last spring while flipping through a little book of traditional Ukrainian clothes from the 1980s. For five months, she perfected the design — researching techniques and materials used in typical Ukrainian headdresses.

Building from a traditional design, Lomachenko added ceramic roses, bamboo leaves and feathers to her white crown. Often Ukrainian headdresses are bursting with color, but Lomachenko settled on white to emphasize the many textures and eccentric accents in her own ensemble. Too much color would have made it too loud, she said.

Lomachenko carefully assembled dozens of pieces of fabric, thread, ceramic roses, leaves and feathers in one night. Her vinok is a celebration of Ukrainian culture, she said.

“I don’t want to paint war,” Lomachenko said. But, “in some ways, I have to.”

One of Lomachenko’s closest friends is from Crimea. She fled the occupied region for Kyiv in 2014. Now she’s a refugee for the second time. Many people close to Lomachenko, she said, have been “running from war.”

Lomachenko’s grandmother is still in the capital. She calls to check on her and other relatives every couple of days.

On Friday, her grandmother told her things were “relatively calm” in the capital, but she and many others are scared.

The Pentagon said photos of mass graves and other images coming out of Bucha, a city near Kyiv, reinforce evidence that Russian forces committed war crimes, The Washington Post reported Monday.

Since Russian forces invaded Ukraine, Lomachenko said she has felt on edge. Although she hasn’t heard air strike sirens herself, the school bells marking new class periods have made her lurch out of her seat.

Recently, Lomachenko said she has poured her energy into her creative projects that help explain the war, and share Ukrainian culture.

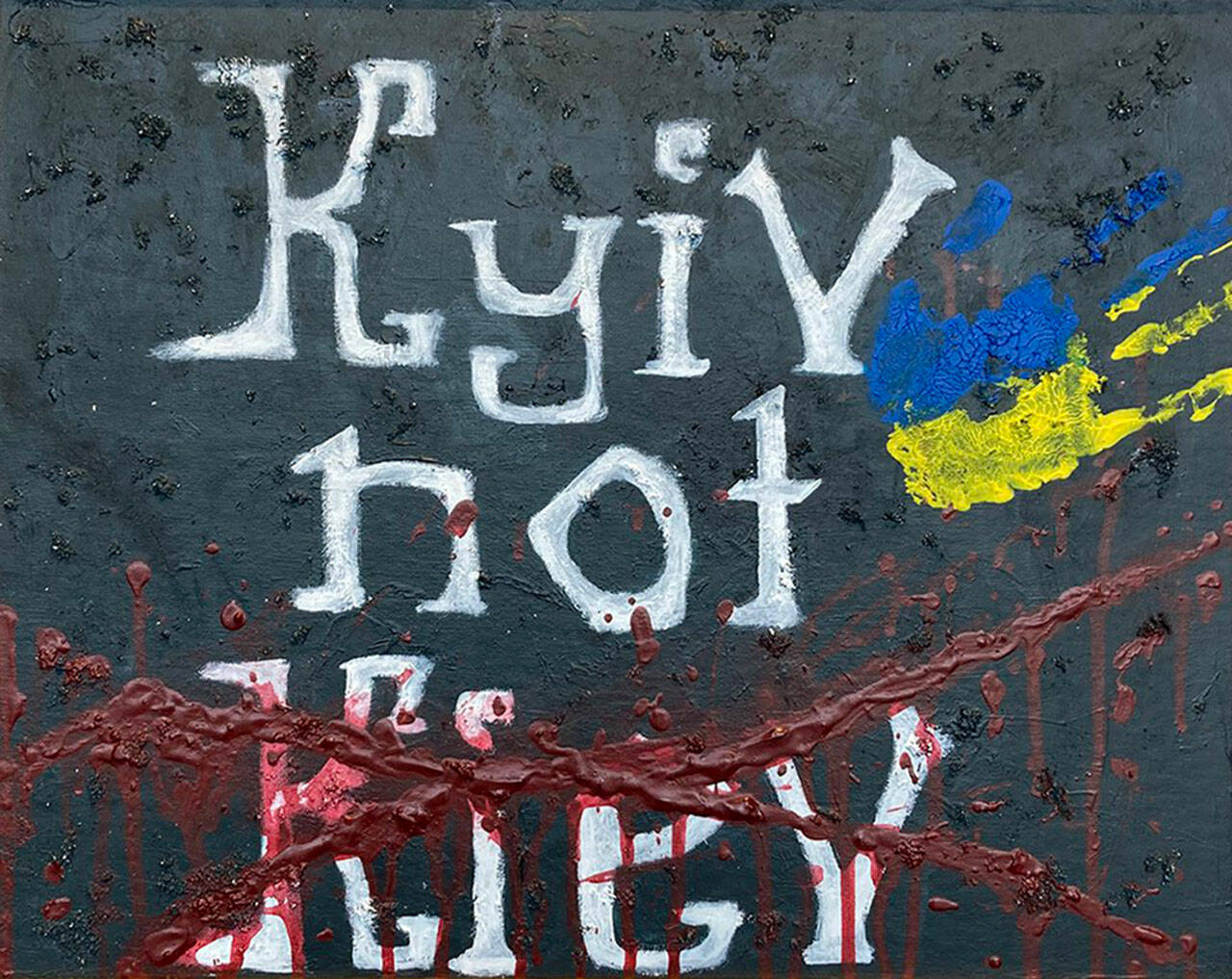

The A/NT Gallery in Seattle is displaying one of those pieces, “Kyiv not Kiev.”

The painting explains the fight for Ukrainian independence from Russia, Lomachenko said. A red splotchy “X” is painted over “Kiev,” the Russian pronunciation of the Ukrainian capital city. The dripping red paint signifies blood, for the many who have died resisting Russian influence on their country. A blue and yellow handprint beside “Kyiv” symbolizes the hope for freedom and independence.

“I think that I have to show the world not only the war, but also the good things that are happening there in the culture,” Lomachenko said. “And raise interest in the country.”

When photos of her headdress started gaining traction on social media, Lomachenko said she felt like she was starting to accomplish that. The headdress is easily recognizable as a traditional piece of fashion by Lomachenko’s friends and family in Ukraine, she said. But in Snohomish, it may be some of her classmates’ first introduction to the culture.

“I’m really proud of her, as any parent would be,” Thibault said.

Thibault said she first realized her daughter’s ability to create when Lomachenko was a toddler.

By six years old, Thibault recalled, her daughter’s teacher noticed Lomachenko “doesn’t see as everyone else.” At that age, most kids draw flat pictures, but Lomachenko’s had dimensions, Thibault said.

In her few years in Snohomish County, Lomachenko has received three Schack Art Center awards for her individual works: “Wise vase,” “Wall decor” and “Cabbage.” She hopes to attend art school in the fall.

“I’m better with art than I am with words — it’s easier for me to show it visually than to explain it,” Lomachenko said. “I have things that I want the world to hear. And art is a tool I can use.”

Isabella Breda: 425-339-3192; isabella.breda@heraldnet.com. Twitter: @BredaIsabella.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.