EVERETT — It’s a hard offer to turn down once the withdrawal symptoms begin — nausea, shaking hands, agitation. When an inmate starts to display those signs, usually soon after they’re booked into the Snohomish County Jail, the medical staff has something new to offer: Suboxone. The prescription can lessen the discomfort and cravings that come with withdrawal.

By default, the jail had become one of the largest drug detox centers in the county. More than one out of three people brought in test positive for opioids. Frequently, the jail’s medical unit operates at 150 to 200 percent above capacity, forcing the jail to turn away bookings for non-violent misdemeanors if the arrestees had medical or mental health needs.

As opioids use was declared an epidemic by county officials, Sheriff Ty Trenary knew he couldn’t just arrest his way out of the problem. The jail had become a revolving door for people struggling with addictions, a pattern seen across the country.

“It’s taxing on the jail,” said Alta Langdon, a nurse practitioner and health services administrator there. “I’ve seen sick people but I have never seen sick people like I’ve seen in withdrawal. It’s awful.”

“If we can offer relief, why wouldn’t we?” Langdon asked.

The drug is easing the strain on the jail, and offers a long-term treatment option, officials say. It also reduces the health hazards associated with detoxing, which can be fatal.

Bringing Suboxone and medication-assisted treatment and detox into the jail wasn’t easy.

Suboxone is classified as a controlled substance. The new thinking was in contrast to ideas that were deeply rooted in jail systems.

“It went against the grain,” said Tony Aston, the sheriff’s corrections bureau chief. “You don’t bring drugs into a maximum security facility.”

Aston said his bosses, including the sheriff, were “dead set against the idea,” at the beginning.

There was pushback, Langdon said. While Suboxone contains opioids, it’s different than heroin or fentanyl. It is a partial agonist, meaning it doesn’t bind perfectly to receptors in the brain and produces weaker ups and downs than other opioids. It also contains the overdose prevention drug naloxone.

“We are talking about bringing a controlled substance in to treat a controlled substance withdrawal,” she said. “It was hard for them to wrap their brains around it. So much of what we do in the jail is to try and minimize contraband and minimize diversion of medications.”

In January, the jail launched one of the first programs in the state to offer detainees access to medication to ease withdrawals. It was one of five recently highlighted in a National Sheriffs’ Association report on jail-based medication-assisted treatment, also known as MAT.

Dopesick

It was the fear of dope sickness that for years stopped Lindsey Wakeman from getting help. She got hooked on heroin as a cheaper substitute to her $100-a-day pain pill habit.

“I tried it. I smoked it. I liked it,” Wakeman said.

For years the Everett resident was able to hold down a job, but her addiction eventually caught up with her. She lost her job, then her apartment earlier this year.

“I was really mad at myself that I let it get that bad,” she said.

She began to shoplift to pay for drugs.

“It was only a matter of time before I ended up in jail,” Wakeman said.

Homeless, though not yet involved in the criminal justice system, she found her way to the county’s Diversion Center, through a law enforcement team that includes embedded social workers. At the center, MAT and case management is offered to homeless adults living with addiction, also in an effort to stem the cycle of drug use, homelessness, crime and arrest.

“The reason many addicts don’t go into detox is because of the sickness of it,” Wakeman said.

The Suboxone prescribed at the center curbed her withdrawal symptoms but also offered a way forward.

She spent 10 days at the center, then 30 days in inpatient treatment in Yakima. Today, at age 40, she lives at a clean and sober house in south Everett. She plans to start therapy soon to address the underlying causes of her addiction.

“If I wasn’t on Suboxone, I don’t think I’d be clean,” Wakeman said.

Before someone can start the prescription, withdrawal symptoms must first begin. As nausea and anxiety set in, few inmates in the jail say no to an offering that will curb those feelings.

“It feels like somebody threw a stinking lifeline,” said Geoffrey Godfrey, a nurse practitioner at Ideal Option, an addiction medicine clinic that has partnered with the county. “You feel like crap for a long time and your crappy feeling is just incrementally getting worse and worse and worse.”

In a day after starting Suboxone, inmates in the jail are out of the medical unit and back with the general population.

“And so a lot of them say I need this when I leave here,” Langdon said. “The idea is that they begin to understand that there’s a better solution to their addiction than using again.”

Resources and federal regulations limit the Suboxone patient load at the jail to 90, so many are weaned off the medication soon after starting. Doctors are capped at 30 patients the first year they prescribe Suboxone.

“Our solution was to come up with this taper. So at least they’re not experiencing severe withdrawal,” Langdon said. “It’s not my first choice but it’s the best choice we have with what we have and it works.”

People who are booked into jail already on Suboxone are able to continue their treatment through their stay. And pregnant detainees, 90 percent of whom test positive for opioids, are prescribed a similar drug and remain on it to protect their unborn child.

Some inmates are provided a chance to go back on the medicine as they prepare to leave the jail. It depends on resources and what’s in store for them after release. That alternative is not available for everyone, such as those transferring to other jails or prisons.

Warm handoff

Simply leaving the jail is a trigger for many. The county was finding that people who had gone through detox behind bars were coming right back in again with opioids in their system.

It’s become their habit for so long to come to the jail and not have anything, and the first thing they want to do is go use, Langdon said. “And when you’re fighting that kind of a disease it’s about instant gratification. It’s not about what’s going to happen next week.”

People need to be picked up and dropped off at the clinic, rather than just sending them out of the jail with a piece of paper, she said.

“That warm handoff is really priceless. I think it’s key to where we’re at now,” she said.

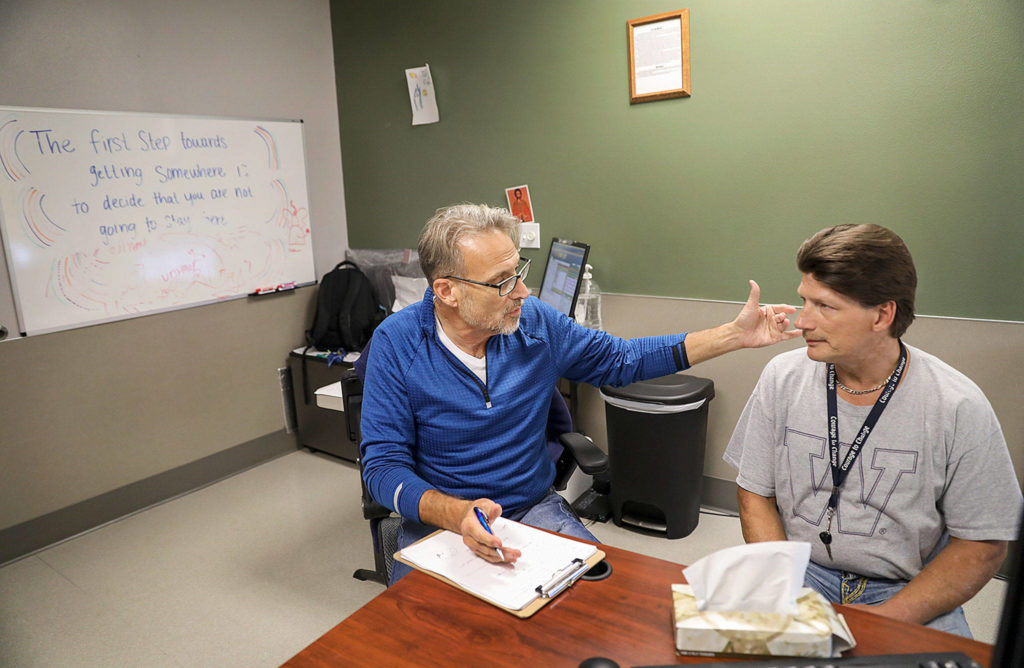

That approach shows folks that someone cares about them, said Dr. Jeffrey Allgaier, president and CEO of Ideal Option.

For many years drug use has been treated as a crime and people are thrown in jail and forced to withdrawal, Allgaier said.

“As evidence mounts, we are realizing that is not the right thing to do,” he said. “And the recidivism rates where they go back to jail and the death rates were so high, that we are now learning to develop partnerships.”

“Us doctors are realizing that there’s a huge component of law enforcement that needs to be there, and they are realizing there’s a huge component of medical that needs to be here,” Allgaier added. “We are working together in ways we’ve never seen before.”

Since 2013, the medical staffed has increased about 60 percent, according to data provided by the sheriff’s office.

“It used to be a jail with a couple of nurses,” Aston said. “Now there’s a huge medical component with a nice security component to it.”

Embracing a new approach

Langdon didn’t always see MAT as a solution. Before coming to the jail, she worked as a primary care nurse for nearly a decade. There she would steer her patients to other recovery programs, believing at the time that MAT just replaced opioid for another opioid.

The gravity of the situation, an over-capacity medical unit filled with detoxing people, compelled her to reconsider.

“The sheer number was shocking, absolutely shocking to me,” Langdon said.

She became a supporter of MAT after spending time with an addiction specialist and seeing the medicine at work.

MAT, coupled with therapy and counseling, has become the gold standard of care, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Office of the Surgeon General.

An “abstinence-based program,” which means counseling and sobriety without medication, is not based on evidence and is an inhumane treatment that is no longer accepted in the medical community as a response to opioid addiction, Allgaier said.

Treatment without medication results in a relapse rate over 90 percent and a high death rate, Allgaier said.

His clinic has locations throughout the country and serves roughly 1,000 people in Snohomish County.

“What Snohomish County and Everett were willing to do is look at the hardcore evidence … and be willing to implement the most evidence-based treatment, without worrying so much about the emotional reaction and that takes bold courage,” Allgaier said.

Lizz Giordano: 425-374-4165; egiordano@heraldnet.com; Twitter: @lizzgior.

Talk to us

> Give us your news tips.

> Send us a letter to the editor.

> More Herald contact information.